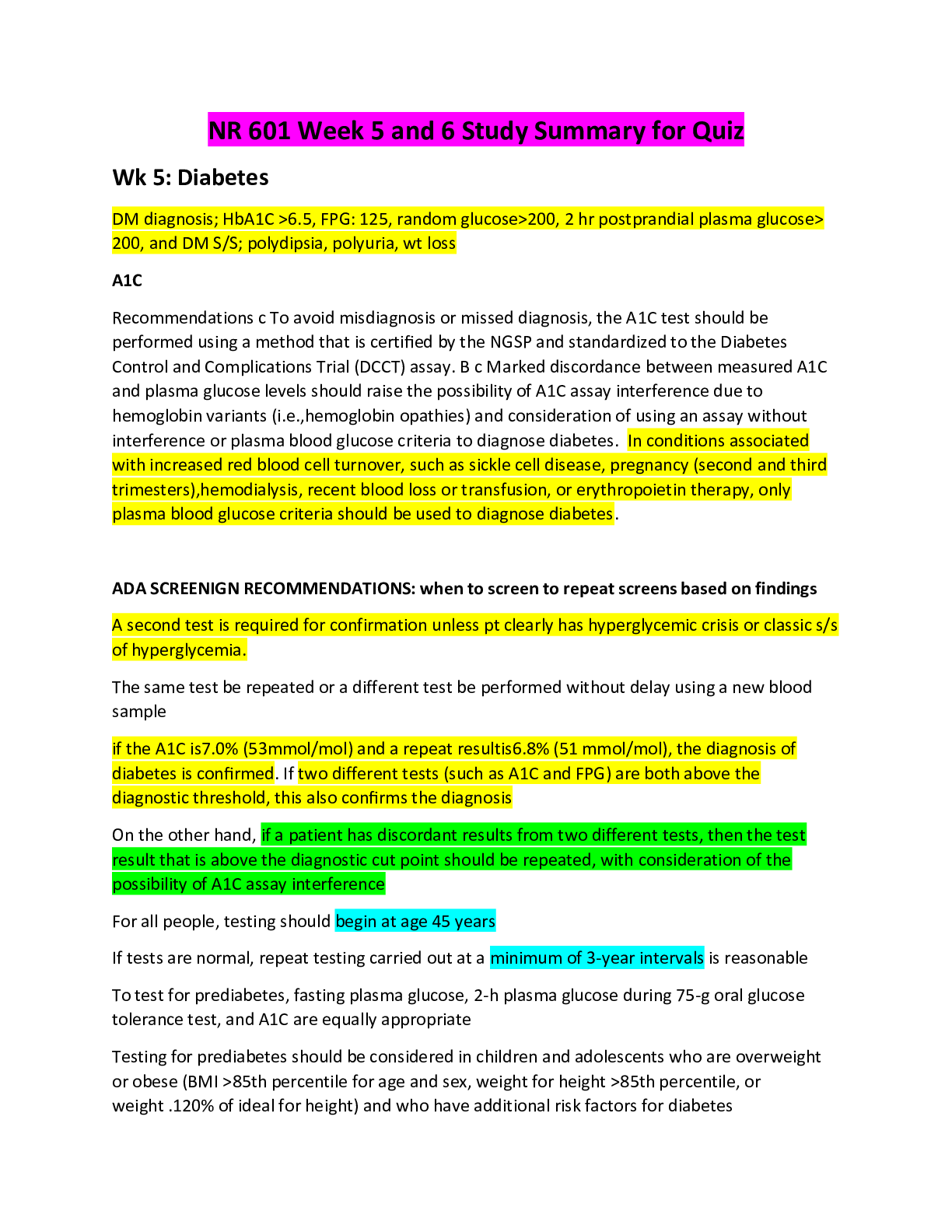

NR 601 Week 5 and 6 Study Summary for Quiz

Wk 5: Diabetes

DM diagnosis; HbA1C >6.5, FPG: 125, random glucose>200, 2 hr postprandial plasma glucose> 200, and DM S/S; polydipsia, polyuria, wt loss

A1C

Recommendations c

...

NR 601 Week 5 and 6 Study Summary for Quiz

Wk 5: Diabetes

DM diagnosis; HbA1C >6.5, FPG: 125, random glucose>200, 2 hr postprandial plasma glucose> 200, and DM S/S; polydipsia, polyuria, wt loss

A1C

Recommendations c To avoid misdiagnosis or missed diagnosis, the A1C test should be performed using a method that is certified by the NGSP and standardized to the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) assay. B c Marked discordance between measured A1C and plasma glucose levels should raise the possibility of A1C assay interference due to hemoglobin variants (i.e.,hemoglobin opathies) and consideration of using an assay without interference or plasma blood glucose criteria to diagnose diabetes. In conditions associated with increased red blood cell turnover, such as sickle cell disease, pregnancy (second and third trimesters),hemodialysis, recent blood loss or transfusion, or erythropoietin therapy, only plasma blood glucose criteria should be used to diagnose diabetes.

ADA SCREENIGN RECOMMENDATIONS: when to screen to repeat screens based on findings

A second test is required for confirmation unless pt clearly has hyperglycemic crisis or classic s/s of hyperglycemia.

The same test be repeated or a different test be performed without delay using a new blood sample

if the A1C is7.0% (53mmol/mol) and a repeat resultis6.8% (51 mmol/mol), the diagnosis of diabetes is confirmed. If two different tests (such as A1C and FPG) are both above the diagnostic threshold, this also confirms the diagnosis

On the other hand, if a patient has discordant results from two different tests, then the test result that is above the diagnostic cut point should be repeated, with consideration of the possibility of A1C assay interference

For all people, testing should begin at age 45 years

If tests are normal, repeat testing carried out at a minimum of 3-year intervals is reasonable

To test for prediabetes, fasting plasma glucose, 2-h plasma glucose during 75-g oral glucose tolerance test, and A1C are equally appropriate

Testing for prediabetes should be considered in children and adolescents who are overweight or obese (BMI >85th percentile for age and sex, weight for height >85th percentile, or weight .120% of ideal for height) and who have additional risk factors for diabetes

Criteria for testing for diabetes or prediabetes in asymptomatic adults

1. Testing for prediabetes and risk for future diabetes in asymptomatic people should be considered in adults of any age who are overweight or obese (BMI >25 kg/m2 or >23 kg/m2 in Asian Americans) and who have one or more additional risk factors for diabetes:

• First degree relative with DM

• High risk race; AA, latino, native American, Asian American, pacific islander

• History of CVD

• HTN (>140/90 or on tx for HTN)

• HDL cholesterol level <35 and triglyceride level>250

• Women with polycystic ovary syndrome

• Physical inactivity

• Other clinical conditions associated with insulin resistance; severe obesity acanthosis nigricans

2. Pt with prediabetes ((A1C >5.7% [39 mmol/mol], IGT, or IFG) should be tested yearly)

3. Women who were diagnosed with GDM should have lifelong testing at least every 3 years

4. For all other patients, testing should begin at age 45 years.

5. If results are normal, testing should be repeated at a minimum of 3-year intervals, with consideration of more frequent testing depending on initial results and risk status.

Guideline recommendations to start medications

Metformin therapy for prevention of type 2 DM should be considered in those with prediabetes, especially for those with BMI>35, those aged <60 years, and women with prior gestational DM

First line medication options and medication side effects

Metformin

- good for glucose control and also good for reducing risk of macro and microvascular outcomes, especially those overweight and obese patients

- the best risk benefit profile drug for type 2 DM

- does not stimulate endogenous insulin secretion enhance tissue responsiveness to insulin

- well-absorbed in the small intestine, peak plasma concentrations in 2 hours, rapidly excreted by the kidneys

- impaired renal function, Cr for men >1.5, and >1.4 for women is contraindication

- 500mg once daily and increase to BID in 1 to 2 weeks, max is 2000 to 2500mg/day

- The most common side effect: GI UPSET (Nausea, diarrhea, bloating, abdominal pain)

- Lactic acidosis; the most serious adverse side effect; pts with hypoxemia, hypovolemia, and decreased tissue perfusion and renal insufficiency are more prone to it

Sulfonylureas (glyburide, glipizide, glimepiride)

- Treatment for mild to moderate severe DM 2 (glucose 140-240)

- Increase the sensitivity of beta cells to glucose and stimulate endogenous insulin release by binding to a specific beta-cell receptor

- Adverse effect: hypoglycemia, cardiovascular risk, wt gain

Insulin

Short and rapid acting insulins prandial glycemic control

- Insulin lispro, insulin aspart, and insulin glulisine

- Onset 5 to 15 minutes, a peak at 45 to 75 minutes, duration 2 to 4 hours

- Better match between insulin administration and food intake, helping to improve compliance and reducing the risk of hypoglycemic reactions

Intermediate-acting insulin basal glycemic control

- NPH: onset in 2 hrs, peak at 6 to 10 hrs, duration of 8 to 24 hours.

Long acting insulin analogues

- Insulin glargine and insulin detemir; steady absorption pattern over 24 hours

Mixture of intermediate and short/rapid acting insulin

- Mixture of NPH and rapid acting insulin

- Do not afford flexibility of dose adjustment and should be considered only after optimal doses of intermediate and short/rapid acting insulin have been established independently

2017 HTN guidelines recommended BP ranges for DM

While the Association recommends a blood pressure target of less than 140/90 mmHg for most people with diabetes and hypertension, a lower blood pressure goal might be beneficial for some patients who have a high risk of cardiovascular disease.

Subjective sings of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia

Hyperglycemia

• Extreme thirst

• Frequent urination

• Feeling tired

• Listlessness

• Nausea

• Dizziness

Hypoglycemia

• Racing pulse

• Cold sweats

• Pale face

• Headache

• Feeling incredibly hungry

• Shivering, feeling weak in the knees

• Feeling restless, nervous or anxious

• Difficulty concentrating, confusion

Physical signs of elevated glucose you might see on exam

Fatigue, headaches, blurred vision, frequent urination, increased thirst, difficulty concentrating, dry mouth, increased hunger, confusion, sob, abdominal pain

WEEK 6 GYN and GU

GU

Incontinence in men and women- common causes and types of incontinence

men

Urge incontinence (overactive bladder); a sudden urge to urinate and the bladder involuntarily expels urine, the most common incontinence in men, often due to BPH

Stress incontinence; coughing, sneezing, laughing, heavy lifting, exercise

Mixed incontinence; combination of stress incontinence and urge incontinence

Post micturition dribble: when the bladder doesn’t empty completely and continues to leak after urinating due to BPH or weakened pelvic floor muscles

Functional incontinence; inability to reach the bathroom

Neurological bladder disorder: damage to the nerves as result of Parkinson’s disease, MS

Overflow incontinence: a constant flow of urine due to obstruction or nerve damage

Women

Pregnancy, childbirth, menopause

Diagnoses which present as urinary difficulty in men

BPH, kidney stones, UTI

BPH: DIAGNOSIS TESTING, common medication and most common side effects, and recommended follow up

DRE: direct rectal exam; a person may need a DRE if he or she has symptoms such as rectal bleeding, a change in bowel habits, urethral discharge or bleeding, or a change in urine stream.

The symptoms of BPH usually begin after age 50. The most common symptoms of BPH include:

●Frequent urination, especially at night

●A hesitant, interrupted, or weak stream of urine

●The need to urinate frequently

●Leaking or dribbling of urine

Rectal exam – Your doctor or nurse will need to perform a rectal examination to feel the size and shape of the prostate gland. A rectal exam can help to determine if there are signs of prostate cancer (figure 2).

●Urinalysis – You might be asked for a urine sample to see if you have a bladder infection. (See "Patient education: Urinary tract infections in adolescents and adults (Beyond the Basics)".)

●Blood tests – A blood test to check the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) level is recommended. PSA is a protein produced by prostate cells; the PSA level may be increased in men with BPH. Men who have prostate cancer often have a highly disproportionately elevated PSA level, although prostate cancer is also found in men who do not have an elevated PSA.

Having BPH does not increase your risk for prostate cancer. However, it is possible to have both BPH and prostate cancer at the same time. If your PSA test is higher than normal, you will need further testing to be sure that you do not have prostate cancer. (See "Patient education: Prostate cancer screening (Beyond the Basics)".)

Urodynamic study — A bladder test, known as a urodynamic study, might be recommended for some men who have signs or symptoms of BPH. This test can give information about how well the bladder and urethra are working.

Medicines — The types of medicine used to treat BPH include alpha blockers and alpha-reductase inhibitors; men who also have erectile dysfunction may consider a phosphodiesterase inhibitor. Most men with BPH who start taking a medicine will need to take it forever to relieve symptoms unless they have some type of prostate surgery. (See "Medical treatment of benign prostatic hyperplasia".)

Alpha blockers — These medications relax the muscle of the prostate and bladder neck, which allows urine to flow more easily. There are at least five medications in this category: terazosin (Hytrin), doxazosin (Cardura), tamsulosin (Flomax), alfuzosin (Uroxatral), and silodosin (Rapaflo). Terazosin and doxazosin were initially developed to treat high blood pressure but were later found to be useful for men with BPH.

Alpha blockers begin to work quickly and are usually recommended as a first-line treatment for men with mild to moderate symptoms.

The most important side effects of alpha blockers are dizziness and low blood pressure after sitting or standing up. Terazosin and doxazosin are usually taken at bedtime (to reduce lightheadedness). The dose can be increased over time if needed.

You should not take terazosin and doxazosin if you take a medicine for erectile dysfunction (ED), such as sildenafil (Viagra), vardenafil (Levitra), tadalafil (Cialis), or avanafil (Stendra). Tamsulosin and alfuzosin usually do not interact with ED medications.

Alpha-reductase inhibitors — Alpha-reductase inhibitors are medicines that can stop the prostate from growing further or even cause it to shrink. Finasteride (Proscar) and dutasteride (Avodart) are alpha-reductase inhibitors.

This type of medicine works better in men with a larger prostate. It can reduce the risk of urinary retention (not being able to empty the bladder) and the need for surgery. Most men see an improvement within six months of starting treatment.

A small percentage of men who take alpha-reductase inhibitors have decreased sex drive, difficulty with erection or ejaculation, or symptoms of depression. Sometimes, these problems are significant enough to cause men to interrupt BPH treatment. They resolve when the medication is stopped.

PSA levels decrease by about 50 percent in men who take finasteride or dutasteride. This is important to remember if you have PSA testing to screen for prostate cancer. (See "Patient education: Prostate cancer screening (Beyond the Basics)".)

Phosphodiesterase inhibitors — Tadalafil is a reasonable treatment to consider if you have erectile dysfunction and mild or moderate lower urinary symptoms. Daily tadalafil has been demonstrated to improve symptoms; however, some studies failed to show significant difference in urine flow.

Phosphodiesterase inhibitors must not be used by men who take nitrates or have very decreased kidney function.

Combination treatment — A combination of an alpha blocker and an alpha-reductase inhibitor might be recommended for certain men. This may benefit men:

●With severe symptoms

●With a large prostate

●Who do not improve with the highest dose of an alpha blocker

Genitourinary syndrome of menopause or GSM is an umbrella term for a constellation of menopausal symptoms associated with the physical changes of the vagina, vulva and lower urinary tract (Kim et al., 2015).

• Genital symptoms may be dryness, irritation or burning.

• Sexual symptoms may include dyspareunia or lack of lubrication

• Urinary symptoms may include dysuria, recurrent UTI’s or urgency

Low dose estrogen therapy

• Estrogen creams: these are messy and require reusable applicators but offer a moisturizing effect. Creams must be used with caution in breast cancer patients because the dosing is difficult to manage (Faubion et al., 2017).

• Vaginal estradiol tablets that are inserted daily for the first 2-weeks then two times/week after. The tablets offer a more controlled dosing and would be preferable for patients that need more precise measurement of how much estrogen they are getting (Faubion et al., 2017).

• Estradiol vaginal rings offer sustained release dosing and can be kept in place for 90-days. There are 2 versions of the ring:

• A lower dose ring that releases 7.5 micrograms/day of estradiol and is effective for only GSM symptoms

• A higher dose ring that releases either 0.05mg or 0.1 mg/day and is effective for both GSM and vasomotor symptoms as well because it delivers locally and systemically (Faubion et al., 20167.

Prostatitis signs and symptoms assessment and treatment

usually caused by gram-negative organisms;

E. coli – 58 to 88 percent

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONSThe clinical presentation of acute prostatitis is generally not subtle. Patients are typically acutely ill, with spiking fever, chills, malaise, myalgia, dysuria, irritative urinary symptoms (frequency, urgency, urge incontinence), pelvic or perineal pain, and cloudy urine. Men may also complain of pain at the tip of the penis. Swelling of the acutely inflamed prostate can cause voiding symptoms, ranging from dribbling and hesitancy to acute urinary retention. Rarely, patients lack these local symptoms and present instead with constitutional symptoms or a flu-like illness.

On exam, the prostate is often firm, edematous, and exquisitely tender. Common laboratory findings include peripheral leukocytosis, pyuria, bacteriuria, and, occasionally, positive blood cultures. Inflammatory markers (erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein) are elevated in most cases. Inflammation of the prostate can also lead to an elevated serum prostate specific antigen (PSA) level [27]. Thus, if serum PSA testing for prostate cancer screening is planned, it should be deferred for one month following resolution of acute prostatitis.

Complications — Complications of acute bacterial prostatitis include bacteremia, epididymitis, chronic bacterial prostatitis, prostatic abscesses, and metastatic infection (eg, spinal or sacroiliac infection) [28]. Patients with underlying valvular heart disease or a valvular prosthesis are at risk for endocarditis when prostatitis is caused by certain bacterial pathogens, particularly, but not exclusively, gram-positive bacteria. These complications are more likely to occur if diagnosis and antimicrobial therapy is delayed.

Prostatic abscess — The incidence of prostatic abscess is currently low with the use of appropriate antibiotic therapy [29]. In a prospective study of transrectal ultrasonography of the prostate in 45 men hospitalized for acute bacterial prostatitis, no lesions with sonographic characteristics of prostatic abscesses were identified, despite detection of other, often transient, prostatic lesions in almost half of the men [30]. Certain underlying conditions, such as diabetes mellitus or HIV-related immunosuppression, may predispose to the development of prostatic abscesses [31,32].

Signs and symptoms of a prostatic abscess are similar to those of bacterial prostatitis in general, but may persist despite appropriate antibiotic therapy; in addition, fluctuance of the prostate on gentle digital exam can suggest an underlying abscess. On transrectal ultrasound, abscesses appear as hypoechoic or anechoic areas with thick walls or peripheral edema [32,33]. Computed tomography (CT) findings include nonenhancing fluid-density collections that can be multiseptated or rim-enhancing lesions.

DIAGNOSIS The presence of typical symptoms of prostatitis should prompt digital rectal exam, and the finding of an edematous and tender prostate on physical exam in this setting usually establishes the diagnosis of acute bacterial prostatitis. Digital rectal examination should be performed gently; vigorous prostate massage should be avoided since it is uncomfortable, allows no additional diagnostic or therapeutic benefit, and increases the risk for bacteremia. In patients who present with constitutional symptoms only, establishing a diagnosis of acute prostatitis is challenging. Laboratory findings of leukocytosis, pyuria, bacteriuria, or an elevated serum prostate specific antigen (PSA) level can support the diagnosis, and should prompt consideration of digital rectal exam. (See 'Clinical manifestations' above.)

In order to establish the microbial etiology, a urine Gram stain and culture should be obtained in all men suspected of having acute prostatitis. Gram stain of the urine, if positive, can be used as a guide to initial therapy (see 'Antimicrobial therapy' below). Urine culture typically reveals a causative organism in acute prostatitis, unless antibiotics were recently used.

Blood cultures usually are not necessary for microbial diagnosis, and we typically do not perform them for this reason alone. In a retrospective review of 261 men with acute prostatitis in whom urine and blood cultures were collected, blood cultures provided additional microbial information in 14 patients (5 percent) [20]. However, blood cultures are useful to assess for complications in patients with underlying cardiac valvar disease or clinical evidence of impending or severe sepsis.

MANAGEMENT Treatment of acute prostatitis includes antimicrobial therapy and supportive measures to reduce symptoms. Rarely, more invasive intervention is indicated to manage complications.

Indications for hospitalization — Not all patients with acute bacterial prostatitis warrant inpatient hospitalization. Patients who have no major comorbidities, no signs or symptoms of severe sepsis, and who can reliably take and tolerate oral antibiotics, can likely be managed appropriately in the outpatient setting. A short hospital stay in patients suspected of having bacteremia, or for monitoring purposes in those patients who would not otherwise be able to promptly return to medical care in the case of decompensation, may be prudent. Acute urinary retention should also warrant very close observation or hospitalization for bladder catheterization.

Antimicrobial therapy — A variety of antimicrobials may be used for the treatment of acute prostatitis, which should be treated empirically pending culture results. Data on the treatment of acute prostatitis are limited, and there are no comparative trials evaluating the optimal antimicrobial choice. Thus, recommendations for empiric therapy are based on the likelihood of the infecting organism. Although not all antibiotics can penetrate into prostatic tissue, the presence of acute inflammation generally allows entry of drugs that would not otherwise achieve therapeutic levels. (See "Chronic bacterial prostatitis", section on 'Antimicrobial penetration into prostatic tissue'.)

Empiric antibiotic therapy should adequately treat gram-negative organisms unless a urine Gram stain is available and suggests an alternate bacterial cause. For patients with acute prostatitis who can take oral medications, we suggest trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole (one double-strength tab orally every 12 hours) or a fluoroquinolone (ciprofloxacin 500 mg orally every 12 hours or levofloxacin 500 mg orally once daily) as empiric therapy. We typically choose one of these antimicrobial agents because they achieve high levels in prostatic tissue. Although this may not be an issue in the acute setting, where prostatic inflammation allows penetration of a broader range of antibiotics, the ability of an antibiotic to penetrate prostate tissue is thought to be important during prolonged therapy, while inflammation is resolving [35]. The choice between these should take into account patient tolerance and regional patterns of Enterobacteriaceae drug resistance. (See "Acute simple cystitis in women", section on 'Resistance trends in E. coli'.)

Men younger than 35 years who are sexually active and men older than 35 years who engage in high-risk sexual behavior should be treated with regimens that cover N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis [35]. (See "Treatment of uncomplicated Neisseria gonorrhoeae infections", section on 'Preferred regimen for urogenital infection' and "Treatment of Chlamydia trachomatis infection", section on 'First-line agents'.)

Some patients with acute bacterial prostatitis may need to be hospitalized for parenteral antibiotic therapy if they cannot tolerate oral medication, demonstrate signs of severe sepsis, or have bacteremia. In such cases, intravenous levofloxacin or ciprofloxacin may be given with or without an aminoglycoside (gentamicin or tobramycin 5 mg/kg daily, if the creatinine clearance is normal). An intravenous beta-lactam with activity against Enterobacteriaceae with or without an aminoglycoside is an alternate initial regimen for hospitalized patients. The choice between these should take into account patient tolerance and regional patterns of Enterobacteriaceae drug resistance.

Empiric treatment with an intravenous carbapenem or broad-spectrum penicillin or cephalosporin (with or without gentamicin) pending culture and sensitivity data is appropriate for patients who develop nosocomial prostatitis (eg, following a procedure for which they received a prophylactic fluoroquinolone) or who have a history of infections with drug-resistant pathogens, because of the increased risk of infection with a quinolone-resistant organism.

If available, a Gram stain of the urine can be helpful to further guide the empiric antibiotic choice:

●Patients with gram-negative rods on urine Gram stain should be treated as above.

●Gram-positive cocci in chains usually indicate enterococcal infection, which can be treated with amoxicillin (500 mg orally every eight hours) or ampicillin (2 g intravenous every six hours) if parenteral therapy is indicated. Of note, these regimens are not active against most Enterococcus faecium or other ampicillin-resistant strains. (See "Treatment of enterococcal infections", section on 'Approach to resistant strains'.)

●Gram-positive cocci in clusters are most often due to Staphylococcus aureus or coagulase-negative staphylococci (eg, S. epidermidis or S. saprophyticus). Effective oral antibiotics for strains that are not methicillin-resistant include cephalosporins (eg, cephalexin 500 mg orally every six hours) or penicillinase-resistant penicillins (eg, dicloxacillin 500 mg orally every six hours). Choices for parenteral therapy include cefazolin (1 g intravenous every eight hours) or nafcillin (2 g intravenous every four to six hours). If there are risk factors for, or a history of methicillin-resistant S. aureus, vancomycin (15 to 20 mg/kg/dose every 8 to 12 hours, not to exceed 2 g per dose) can be used. (See "Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) in adults: Epidemiology", section on 'Risk factors'.)

Further changes to the empiric antibiotic regimen can be made based on susceptibility data of the isolated organism and clinical response. Of note, although nitrofurantoin is commonly used for lower urinary tract infections in women, we avoid this agent in men with prostatitis because of concern about poor tissue penetration and risk of adverse effects from prolonged use.

Duration of therapy — Patients initiated on parenteral antibiotics can be switched to oral antibiotics, if drug susceptibility and patient tolerance allow, 24 to 48 hours following improvement in fever and clinical symptoms. Antibiotics should be administered for six weeks to ensure eradication of the infection [36].

Clinical data on the duration of treatment for acute bacterial prostatitis are limited. We favor such a prolonged therapy because of limited antimicrobial penetration into the prostate and the development of protected microcolonies deep within the inflamed gland that may be difficult to reach with antimicrobials. Shorter durations of therapy have been associated with progression to chronic symptoms. (See 'Prognosis' below.)

Common causes of ED

- Injury

- Aging!!

- Cardiovascular disease

- DM

- Drugs

- neurogenic

- endocrine disease

- psychogenic

Physical changes related to female urinary complaints and diagnoses

UTI: diagnosis includes secondary testing, be able to interpret UA dipstick findings- know the lab values

What are the 3 most common pathogens for UTIs?

The most common cause for UTI’s Escherichia coli, it is responsible in 75-95% of organisms grown on culture. Staphylococcus saprophyticus is usually responsible for the other 5-15% of organisms found. Occasionally Klebsiella is found, most often in post-menopausal women

Most dipsticks permit the analysis of the following core urine parameters: heme, leukocyte esterase, nitrite, albumin, hydrogen ions, specific gravity, and glucose. Some dipsticks include test pads for additional parameters including urobilinogen and ketones.

Urinalysis Interpretation

Smell:

The normal smell of urine can be described as urinoid.

Other smells of interest include:

Faecal smell: gastrointestinal-bladder fistula

Fruity or sweet smell: diabetic ketoacidosis

Smell of ammonia: alkaline fermentation.

Smell of asparagus: um…er….eating a lot of asparagus.

Colour:

Normal urine colour is often described as straw, yellow or amber.This colour may be altered by

medications, food sources or disease.

Vitamin tablets often result in a bright yellow urine, as does the presence of bilirubin (a bile

pigment).

Red urine may be due to blood, haemoglobin, or beetroot.

Iron supplements may cause a dark brown specimen, as might amounts of prophobilin or

urobilin (a chemical produced in the intestines)

Normal urine is also transparent. Turbid or cloudy urine may result from infection the presence

of blood cells, bacteria or yeast (eg Candida).

A foamy urine may indicate either the presence of glucose or protien.

Leukocytes:

Detects white cells in the urine (pyuria) which is associated with urinary tract infection.

Nitrites:

Nitrites are formed by the breakdown of urinary nitrates. This us usually caused by Gramnegative and some Gram-positive bacteria.

So the presence of nitrites suggests bacterial infection such as E.coli, Staphylococcus and

Klebsiella.

Commonly found during a urinary tract infection.

Urobilinogen:

Normally present in the urine in small quantity. Less than 1% of urobilinogen is passed by the

kidneys the remainder is excreted in the faeces or transported back to the liver and converted

into bile.

Raised levels may be due to:

Cirrhosis

Hepatitis

Hepatic necrosis

Haemolytic and pernicious anaemia

Malaria

Protein:

This is measuring the amount of albumin in the urine. Normally there should be no detectable

quantities.

Elevated protein levels are known as proteinuria. Albumin is one of the smaller protiens, and if

the kidneys begin to dysfuncion it may show an early sign of kidney disease.

Other conditions which may lead to protein in the urine include:

Injury to the urinary tract, bladder or urethra

Inflammation, malignancies.

Multiple myeloma.

pH (that’s pee-H not ffff-H):

Measures the hydrogen ion concentration of the urine.

It is important that a fresh sample be used as urine becomes more alkaline over time as bacteria

convert urea to ammonia (which is very alkaline).

Urine is normally acidic but its normal pH ranges from 4.5 to 8.

Low pH (acidic):

Foods such as acidic fruits (cranberries) can lower the pH, as can high a high protein diet.

As urine generally reflects the blood pH, metabolic or respiratory acidosis can make it more

acidic.

Other causes of acidic urine include diabetes, diarrhoea and starvation.

High pH (alkaline):

Low carb or vegetarian diet

May be associated with renal calculi.

Respiratory or metabolic alkalosis

Urinary tract infection

Haematuria:

Classified as microscopic or macroscopic. Microscopic means that the blood is not visible with the

naked eye.

Blood may be present in the urine following trauma, smoking, infection, renal calculi or

strenuous exercise.

It may also be present with:

Urinary tract infections.

Damage to the glomerulas or tumours which erode the urinary tract.

Acute tubular necrosis.

Traumatic catheterization.

Damage caused by the passage of kidney stones.

Contamination from the vagina during menstruation.

The presence of myoglobin (myoglobinuria) after muscle injury will also cause the reagent strip

to indicate blood.

Specific Gravity:

The specific gravity (SG) of urine signifies the concentration of dissolved solutes and reflects the

effectiveness of the renal tubules to concentrate it ( when the body needs to conserve fluid). If

there were no solutes present the urines SG would be 1.000, the same as pure water.

The SG of urine is around 1.010 but can vary greatly:

Decreased SG may be due to:

Excessive fluid intake (oral or IV fluids)

Renal failure

Acute golmerulonephritis, pyelonephritis, acute tubular necrosis

Diabetes insipidus

Increased SG may be due to:

Dehydration due to poor fluid intake, vomiting or diarrhoea

Heart failure

Liver failure

Inappropriate antidiuretic hormone secretion

It also reflects a high solute concentration which may be from glucose (diabetes or IV glucose)

or protein.

Ketones:

Not normally found in the urine, ketones are produced during fat metabolism.

Presence of ketones may indicate:

diabetes

alcoholism

eclampsia

a state of starvation

pregnancy

Bilirubin:

Produced as a by-product during the degradation of RBC in the liver and normally excreted in

the bile. Once in the intestine it is excreted in the faeces (as stercobilin) or by the kidneys (as

urobilinogen).

Presence of bilirubin in the urine may therefore indicate:

liver disease

biliary tract infection

pancreatic causes of obstructive jaundice.

Glucose:

Glucose is not normally present in the urine.

Once the level of glucose in the blood reaches a ˜renal threshold ™ the kidneys begin to excrete

it into the urine in an attempt to decrease the blood concentration. So high blood concentrations

lead to glucosuria, as does conditions that may reduce this renal threshold.

Diabetes

Liver disease

Medications such as tetracycline, lithium, penicillin, cephalosporins

Pregnancy

Asymptomatic bacteriuria- diagnosis and medical management

Asymptomatic bacteriuria is defined as isolation of a specified quantitative count of bacteria in an appropriately collected urine specimen from an individual without symptoms or signs of urinary tract infection.

Diagnosis

Women: two consecutive clean-catch voided urine specimens with isolation of the same organism in quantitative counts of ≥105 cfu/mL

Men: a single clean-catch voided urine specimen with isolation of a single organism in quantitative counts of ≥105 cfu/mL in the absence of symptoms

Usually no treatment requires, but pregnancy, urologic intervention, renal transplant recipients needs treatment

Microscopic hematuria- diagnosis and medical management

Non-visible haematuria (microscopic); 3 RBCs or more per high-power field

Transient, non-visible haematuria is common and, depending on the studied population, may be reported in as many as 39% of people.3 It is associated with a mixture of urological and glomerular causes. Persistent, non-visible haematuria is defined as urine positive on two out of three consecutive dipsticks, e.g. over a one to two week period. It is estimated to occur in 2.5 – 4.3% of adults seen in primary care. urinary tract infection (UTI) is a common cause of haematuria, this should first be considered and excluded. Non-visible haematuria is often transient so persistence should be confirmed by the presence of two out of three positive dipstick tests, seven days apart

SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS

●Hematuria that is not explained by an obvious underlying condition (eg, cystitis, ureteral stone) is fairly common. In many such patients, particularly young adult patients under the age of 35 years, the hematuria is transient and of no consequence. Fever, infection, trauma, and exercise are potential causes of transient hematuria. (See 'Introduction' above and "Exercise-induced hematuria".)

●Hematuria may be visible to the naked eye (called gross hematuria) or detectable only on examination of the urine sediment by microscopy (called microscopic hematuria) (see 'Definition of hematuria' above):

•Gross hematuria is suspected because of the presence of red or brown urine. The initial step in the evaluation of patients with red urine is centrifugation of the specimen to see if the red or brown color is in the urine sediment or the supernatant (algorithm 2).

•Microscopic hematuria may be discovered when blood (either red blood cells [RBCs] or hemoglobin) is found on a urinalysis or dipstick done for other purposes. Microscopic hematuria is defined as the presence of three or more RBCs per high-power field in a spun urine sediment (picture 1). The urine sediment (or direct counting of RBC per mL of uncentrifuged urine) is the gold standard for the detection of microscopic hematuria; a positive dipstick test should always be confirmed with microscopic examination of the urine.

●Hematuria may be a symptom of an underlying disease, some of which are life threatening and some of which are treatable (figure 1). The causes vary with age, with the most common being inflammation or infection of the prostate or bladder, stones, and, in older patients, a kidney or urinary tract malignancy or benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) (figure 2). (See 'Etiology' above.)

●Our approach to the evaluation of patients with a positive dipstick for heme or with red or brown urine is to confirm the presence of hematuria by microscopic analysis of a centrifuged specimen. After the presence of hematuria is confirmed, the general diagnostic approach is as follows (algorithm 1) (see 'Overall approach to the evaluation' above):

•Microscopic hematuria identified in a woman during her menses, or in a patient shortly after vigorous exercise or acute trauma, should be confirmed by repeating the urinalysis. In menstruating women, the urinalysis should be repeated later in the cycle once menstrual bleeding has ceased. In patients with hematuria identified in the setting of vigorous exercise, the urinalysis should be repeated approximately four to six weeks later during a period of no exercise. Patients with acute trauma and microscopic hematuria should have a confirmatory urinalysis after four to six weeks.

•Patients who present with unilateral flank pain suggestive of obstructive nephrolithiasis should undergo imaging (noncontrast computed tomography [CT] or ultrasound with or without an abdominal radiograph) as the first test in the evaluation (See "Diagnosis and acute management of suspected nephrolithiasis in adults", section on 'Diagnostic imaging'.).

•Patients who have findings suggestive of urinary tract infection (eg, fever, dysuria, presence of white blood cells [WBCs] in the urine, positive dipstick for nitrite) should undergo urine culture to evaluate for urinary tract infection. In patients with urinary tract infection, the infection should be treated and the urinalysis should be repeated approximately six weeks after completion of antibiotic therapy in order to determine if the hematuria is persistent.

•If there is gross hematuria with visible blood clots in the urine, then imaging of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder should be performed, and the patient should be referred for urgent urology evaluation for cystoscopy and further evaluation. If there is gross hematuria without visible blood clots in the urine, patients with acute kidney injury or findings suggestive of glomerular bleeding should be referred to nephrology. Those without such findings should have imaging of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder and possible urology referral, depending upon whether or not they are pregnant. (See 'Glomerular versus nonglomerular bleeding' above and "Definition and staging criteria of acute kidney injury in adults".)

•If there is microscopic hematuria, patients with acute kidney injury or findings suggestive of glomerular bleeding should be referred to nephrology. Those without such findings should have imaging of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder, and possible urology referral if they are pregnant or have risk factors for malignancy. (See 'Glomerular versus nonglomerular bleeding' above and "Definition and staging criteria of acute kidney injury in adults" and 'Risk factors for malignancy'above.)

●In unexplained hematuria that requires imaging of the kidneys, ureters, and bladder, CT of the abdomen pelvis without and with intravenous contrast for urography, also called CT urography (CTU), is recommended in most patients. Two main exceptions exist (see 'Imaging' above):

•In a young patient (eg, age <35 years) with no risk factors for urinary tract malignancy, postcontrast images should not be routinely acquired if noncontrast images of the CTU unambiguously demonstrate nephrolithiasis. This approach minimizes the radiation dose conferred and does not decrease the diagnostic sensitivity of the exam.

•Ultrasound of the kidneys and bladder, not CTU, is the initial exam in the evaluation of pregnant women as this avoids ionizing radiation.

●If no diagnosis is apparent from the history, urinalysis, imaging exams, or cystoscopy, then the most likely causes of persistent isolated hematuria are a mild glomerulopathy and a predisposition to stone disease, particularly in young and middle-aged patients. (See 'Unexplained hematuria' above.)

●Screening for hematuria with routine urinalysis in patients who have no symptoms suggestive of urinary tract disease is not recommended.

GYN

HELAHT MAINTENANCE SCREENIGN RECOMMENDATIONS

Ages 13-18 Years: Screening

Blood pressure

□ Secondary sexual characteristics (Tanner staging)

□ Pelvic examination (when indicated by the medical history)

□ Abdominal examination

□ Additional physical examinations as clinically appropriate

Ages 19-39 Years: Screening

□ Breasts (Offer 1-3 year screening for women ages 25-39 years)

□ Abdomen

□ Pelvic examination: ages 19-20 years when indicated by the medical history; age 21 or older, periodic pelvic examination

□ Additional physical examinations as clinically appropriate

Periodic

□ Cervical cytology:

• Age 21-29 years: Screen every 3 years with cytology alone

• Age 30 years and older: Preferred--Co-test with cytology and HPV testing every 5 years; Option--Screen with cytology alone every 3 years

• Age 25 years and older: the FDA-approved primary HPV screening test can be considered as an alternative to current cytology-based cervical cancer screening methods.

□ Chlamydia and gonorrhea testing (if female is 24 years and younger and sexually active)

□ Genetic testing/counseling (screening for spinal muscular atrophy, cystic fibrosis carrier, and assessment for risk of a hemoglobinopathy should be offered to all women who are considering pregnancy)

□ Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) testing - Physicians should be aware of and follow their states' HIV screening requirements.

Ages 40-64 Years: Screening

□ Breasts (Offer every 1-3 years for women aged 25-39 years; May be offered annually for women 40 years and older)

□ Abdomen

□ Pelvic examination

□ Additional physical examinations as clinically appropriate

Ages 65 Years and Older: Screening

□ Breasts (Offer annually)

□ Abdomen

□ Pelvic examination (When a woman's age or other health issues are such that she would not choose to intervene on conditions detected during the routine examination, it is reasonable to discontinue pelvic exams.)

□ Additional physical examinations as clinically appropriate

Menopausal symptom management suggestions

- Hot flashes; due to estrogen withdrawal and resultant vasomotor instability

- Atrophy of the urogenital epithelium; due to a decrease in skin collagen and causes sexual dysfunction and urinary complaints

- Itching, irritation, discharge, bleeding, or painful intercourse

- Sleep disturbances

- Cardiovascular disease; loss of estrogen decreased in HDL, and increase in LDL

- Osteoporosis; when the micro architecture of bone tissue deteriorates

- Suggestions: hormonal therapy

Normal pelvic exam finding of the post-menopausal women

Note loss of labial and vulvar fullness, pallor of urethral and vaginal epithelium, and decreased vaginal moisture.

Treatments for female urinary incontinence

Modifying contributory factors; before starting any treatment for urinary incontinence, medical conditions and medication should be addressed

Lifestyle modification; weight loss, dietary changes, constipation, smoking sessation

Pelvic floor muscle exercises (especially for stress urinary incontinence) pelvic muscle (Kegel) exercises strengthen the pelvic floor musculature to provide a backboard for the urethra to compress on and to reflexively inhibit detrusor contractions.

Atrophic vaginitis: causes and treatment (GSM)

- Most common cause of vaginal discharge in older postmenopausal women and also in younger women with a hypoestrognic state, such as postpartum or during lactation

- Estrogen deficiency leads to thinning of the vaginal epithelium with a decrease in glycogen stores, which causes a decline in lactobacillus species and subsequent reduction on lacit acid production.

- Vaginal ph increases to up to 7.0 and vaginal flora changes streptococci, coliform bacteria, and gut anaerobes to activate

- Symptoms: vaginal and vulvar burning and soreness, occasional bleeding or itching, and dyspareuria. External burning with urination

- Physical Findings: thine, erythematous surface and scant watery discharge of vaginal mucosa

Laboratory Diagnosis of Atrophic Vaginitis

LABORATORY TEST POSITIVE INDICATION

Wet preparation/cytologic smear of cells from upper one third of vagina Atrophic cytologic changes including increase in proportion of parabasal cells

Ultrasonograhy of uterine lining Uterine lining demonstrating endometrial thinness between 4 and 5 mm13

Serum hormone concentration Low level of circulating estrogen ≤ 4.5

Vaginal pH pH elevation above normal postmenopausal levels (pH exceeding 5)3

Microscopy Elimination of diagnosis of trichomoniasis, candidiasis and bacterial vaginosis

Treatment

ESTROGEN REPLACEMENT

Because the lack of circulating, natural estrogens is the primary cause of atrophic vaginitis, hormone replacement therapy is the most logical choice of treatment and has proved to be effective in the restoration of anatomy and the resolution of symptoms. Estrogen replacement restores normal pH levels and thickens and revascularizes the epithelium. Adequate estrogen replacement therapy increases the number of superficial cells.3 Estrogen therapy may alleviate existing symptoms or even prevent development of urogenital symptoms if initiated at the time of menopause. Contraindications to estrogen therapy include estrogen-sensitive tumors, end-stage liver failure and a past history of estrogen-related thromboembolization. Adverse effects of estrogen therapy include breast tenderness, vaginal bleeding and a slight increase in the risk of an estrogen-dependent neoplasm.14 An increased risk of developing endometrial carcinoma and hyperplasia is conclusively related to unopposed, exogenous estrogen intake.15 Factors that determine the degree of increased risk include duration, dosage and method of estrogen delivery. Routes of administration include oral, transdermal and intravaginal. Dose frequency may be continuous, cyclic or symptomatic. The amount of estrogen and the duration of time required to eliminate symptoms depend greatly on the degree of vaginal atrophy and vary among patients.

Systemic administration of estrogen has been shown to have a therapeutic effect on symptoms of atrophic vaginitis. Additional advantages of systemic administration include a decrease in postmenopausal bone loss and alleviation of vasomotor dysfunction (hot flushes). Standard dosages of systemic estrogen, however, may not eliminate the symptoms of atrophic vaginitis in 10 to 25 percent of patients.16 Systemic estrogen in higher dosages may be necessary to alleviate symptoms. Some women require coadministration of a vaginal estrogen product that is applied locally. Up to 24 months of therapy may be necessary to totally eradicate dryness; however, some patients do not fully respond even to this treatment regimen.10

Other treatment options include transvaginal delivery of estrogen in the form of creams, pessaries or a hormone-releasing ring (Estring). Treatment with a low-dose transvaginal estrogen has proved effective in relieving symptoms without causing significant proliferation of the vaginal epithelium.2,12,14,17 The genitourinary pH level is also lowered, leading to a decreased incidence of urinary tract infections. Absorption rates increase with treatment duration because of the enhanced vascularity of the treated epithelium. The advantage of transvaginal treatment may be a decreased risk of endometrial carcinoma because a lower hormone amount is required to eliminate urogenital symptoms. Negative effects of transvaginal treatment include patient dislike of vaginal manipulation, less prevention of postmenopausal bone loss and vasomotor dysfunction, decreased control of absorption with vaginal creams compared to oral and transdermal delivery, and irregular treatment intervals that may cause patients to forget to administer the treatment.6

Transvaginal rings offer convenience, constancy of hormonal concentration in the blood stream and a therapeutic value equivalent to creams without the need for frequent application. Control of hormone dosage is manipulated by changing the surface area of the ring. Atrophic vaginitis symptoms are relieved (with a dosage of 5 to 10 μg per 24 hours) without stimulation of endometrial proliferation, thereby eliminating the need to add opposing progestogen to the regimen.18 Rings may be removed and reinserted by most patients with little difficulty and can be worn during coitus.

MOISTURIZERS AND LUBRICANTS

Moisturizers and lubricants may be used in conjunction with estrogen replacement therapy or as alternative treatments.17 Some patients choose not to take hormone replacement, or they may have medical contraindications or experience hormonal side effects. Patients who wish to avoid using estrogen should not use moisturizers that contain ginseng because they may have estrogenic properties.19 Moisturizers help maintain natural secretions and coital comfort. The length of effectiveness is generally less than 24 hours.

SEXUALITY

Barriers to assessment, education and treatment

What does the AUA state about drawing PSA levels? PSA tests can generate false positives. The cut point for PSA is 4.9 ng/mL,

1. Recommends against PSA screening in men under 40-years-old. Individualized decision should be made for those who are > 55 years at higher risk, such as African American men, strong family history of metastatic or lethal adenocarcinomas who develop symptoms in early ages.

2. Recommends against screening men ages 40 to 54-years-old at average risk.

3. Men age 55 to 69 years old benefit the most from screening. The recommendations states that testing should be done in this group with shared decision making and should be based on the man’s values and preferences.

4. Routine screening interval of two years or more is preferred in men who have chosen to be screened.

5. Does not recommend routine PSA screening in men older than 70-years-old or in a man with less than 10-15 years life expectancy (Carter et al., 2018).

[Show More]