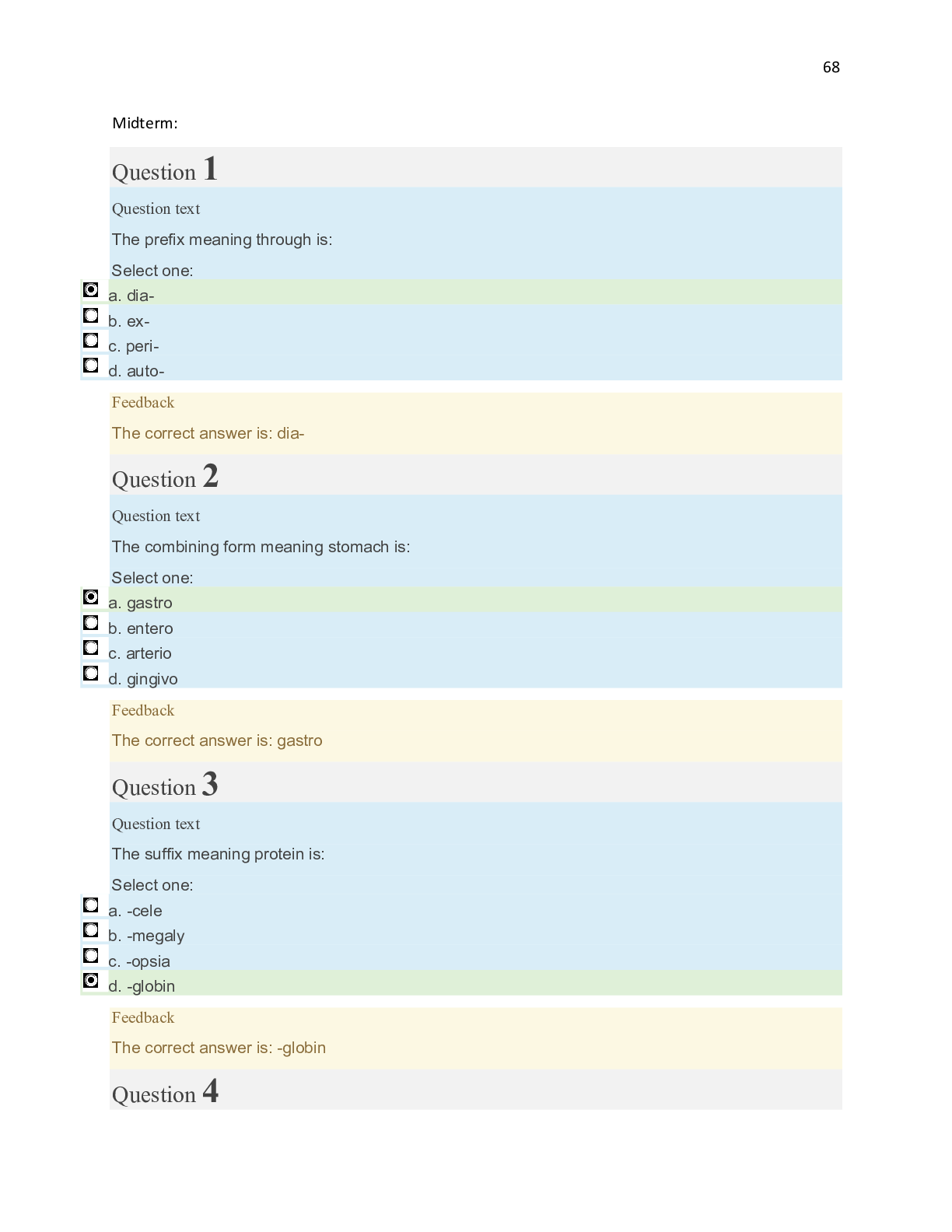

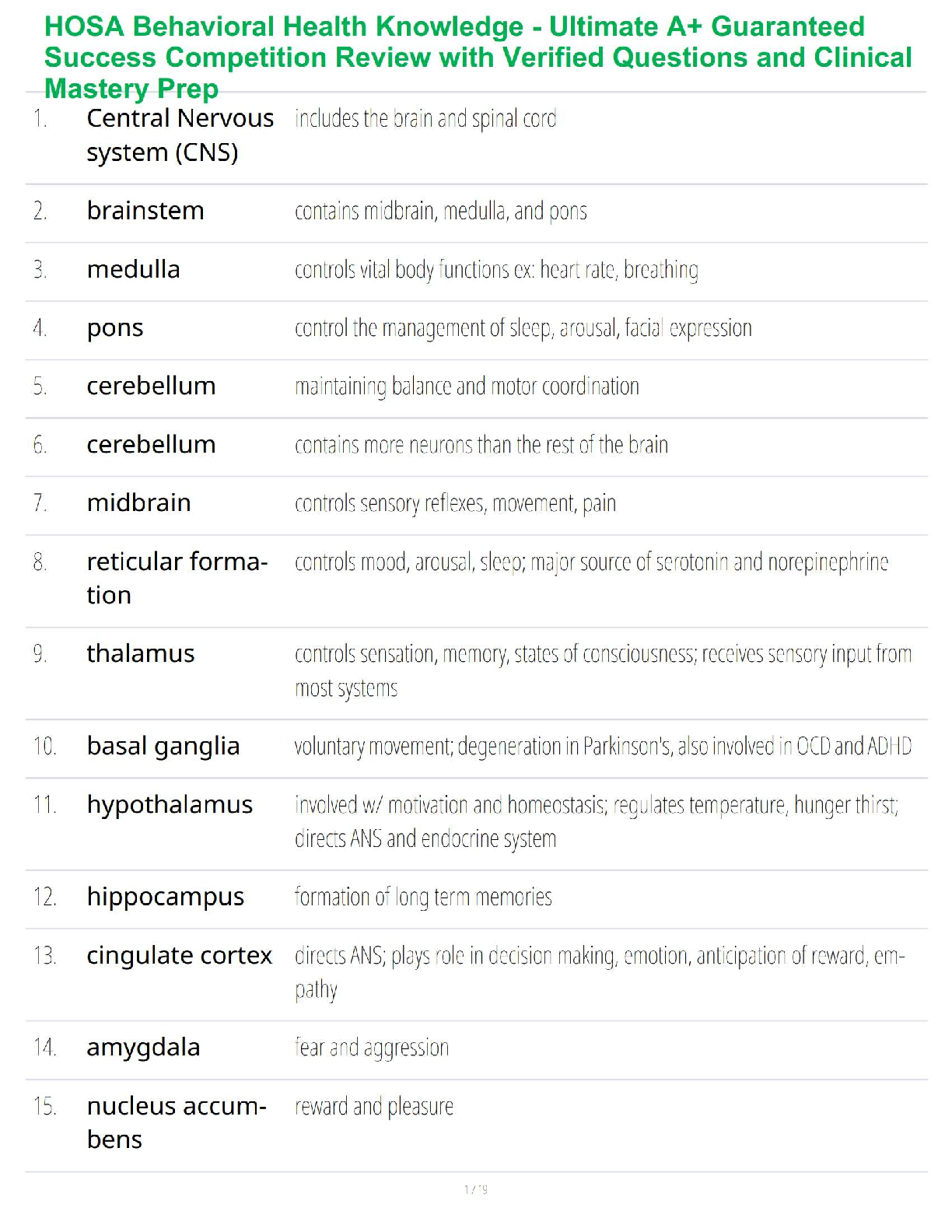

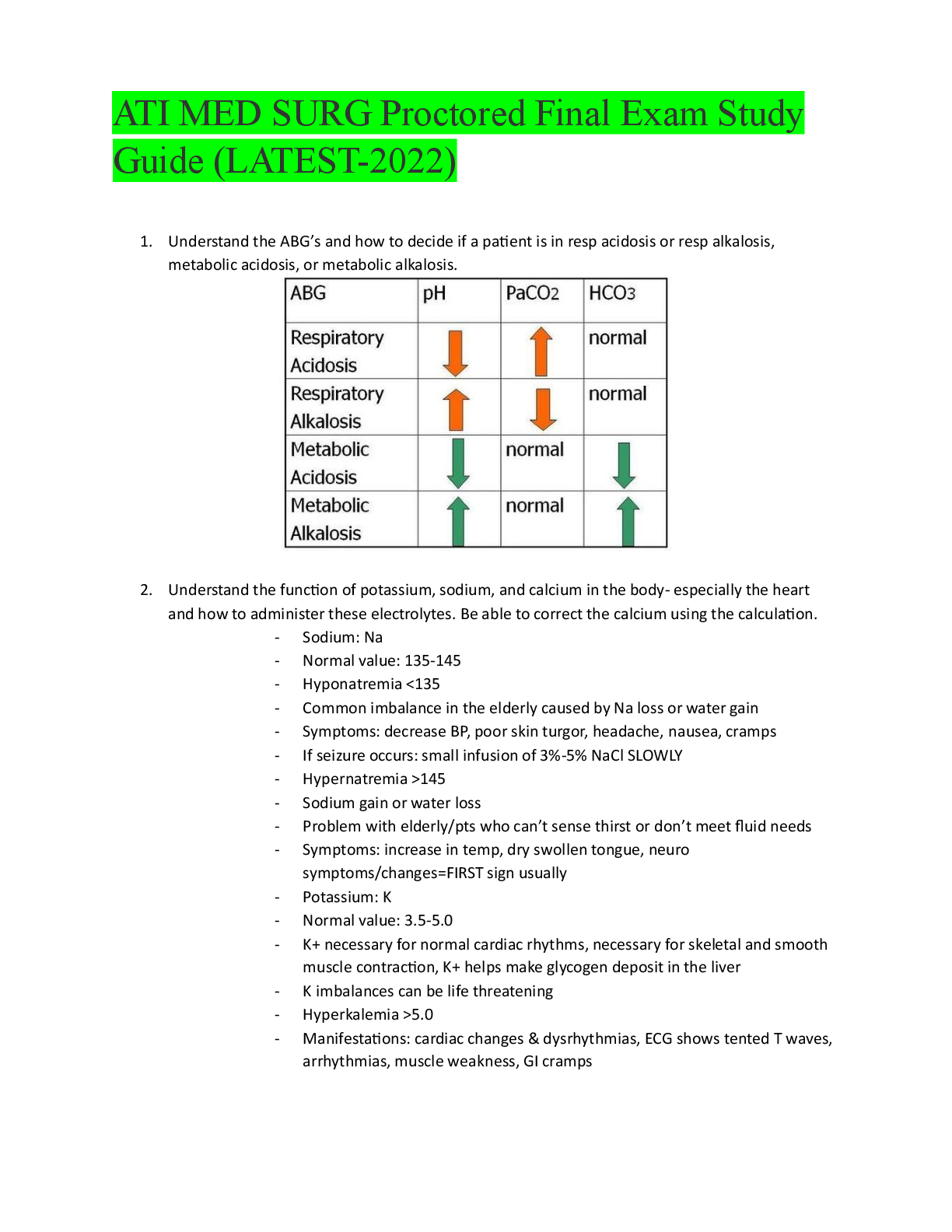

TABLE 23.2 Recommended Order of Treatment for Arrhythmias (Continued )

Order Agents Comments

Sustained

Ventricular

Tachycardia

First line Hemodynamically unstable patient: synchronized DCC

(100 J, biphasic).

Hemod

...

TABLE 23.2 Recommended Order of Treatment for Arrhythmias (Continued )

Order Agents Comments

Sustained

Ventricular

Tachycardia

First line Hemodynamically unstable patient: synchronized DCC

(100 J, biphasic).

Hemodynamically stable patient: IV procainamide,

IV amiodarone, or IV sotalol

Premedicate whenever possible when performing DCC.

Correct reversible causes.

Second line Hemodynamically stable patient: IV lidocaine; synchronized DCC should be considered if AAD therapy fails.

Once arrhythmia acutely terminated, patient should be

considered for ICD placement.

If patient refuses or is not a candidate for an ICD, PO

amiodarone can be considered.

If frequent shocks occur in patients with an ICD, PO amiodarone and β-blocker combination therapy or sotalol

monotherapy can be used.

Pulseless

Ventricular

Tachycardia/

Ventricular

Fibrillation

First line Start CPR, establish an airway, and deliver one shock

(biphasic defibrillator: 120–200 J; monophasic defibrillator: 360 J); immediately resume CPR for 2 min, then

check rhythm.

Correct reversible causes.

Second line If patient remains in pulseless VT/VF, deliver one shock

and then immediately resume CPR; if pulseless VT/VF

persists after at least one shock and CPR, give vasopressor therapy (epinephrine 1 mg IV push/IO every

3–5 min through pulseless VT/VF episode or vasopressin 40 units IV push/IO [to replace first or second dose

of epinephrine]) (give drugs during CPR; do not interrupt CPR to give drugs); immediately resume CPR for

2 min, then check pulse.

Third line If patient remains in pulseless VT/VF, deliver one shock

and then immediately resume CPR; if pulseless VT/

VF persists despite defibrillation, CPR and vasopressor therapy, consider AAD therapy (IV amiodarone;

lidocaine may be used if IV amiodarone unavailable)

(give drugs during CPR; do not interrupt CPR to give

drugs); consider IV magnesium sulfate if torsades de

pointes present; immediately resume CPR for 2 min,

then check pulse.

Bradycardia

First line Patient with stable bradycardia: Close observation

Patients with bradycardia and signs/symptoms of poor

perfusion (e.g., altered mental status, chest pain,

hypotension, shock): Immediately administer

IV atropine (0.5 mg every 3 to 5 min, up to 3 mg total

dose. If the atropine is ineffective, transcutaneous

pacing or sympathomimetic continuous infusion (dopamine or epinephrine) should be initiated.

Correct reversible causes.

Second line If drug therapy and transcutaneous pacing are ineffective, transvenous pacing should be utilized.

AV, atrioventricular; CPR, cardiopulmonary resuscitation; DCC, direct current cardioversion; ICD, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator; INR, International Normalized

Ratio; IV, intravenous; J, joules; LV, left ventricular; LVEF, left ventricular ejection fraction; MI, myocardial infarction; NSVT, nonsustained ventricular tachycardia; PO, oral;

PSVT, paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardia; PVC, premature ventricular contraction; TEE, transesophageal echocardiogram; VF, ventricular fibrillation; VT, ventricular

tachycardia

Arcangelo_Chap23.indd 322 10/8/2011 1:52:29 PM

CHAPTER 23 | ARRHYTHMIAS 323

in those patients with risk factors for thromboembolism, a

TEE-guided approach (see above) can be considered. Those

patients with risk factors for thromboembolism should also be

considered for at least 4 weeks of post-cardioversion anticoagulation therapy (Singer, et al., 2008).

If the practitioner decides to proceed with pharmacologic

cardioversion as the initial therapy, the selection of drug should

be based on the patient’s LV systolic function. Pharmacologic

cardioversion is most effective when initiated within 7 days

of the onset of AF. The AADs with proven efficacy during this time frame include dofetilide, flecainide, ibutilide,

propafenone, or amiodarone (oral or IV). The class Ia AADs,

disopyramide, procainamide, and quinidine have limited

efficacy or have been incompletely studied for this purpose.

Sotalol is not effective for converting AF to SR. Although the

use of single, oral loading doses of propafenone or flecainide

is effective in restoring SR, these drugs should only be used in

patients without underlying SHD. Ibutilide may also be considered in these patients. A patient’s ventricular rate should be

adequately controlled with AV nodal-blocking drugs prior to

administering a class Ic (or class Ia) AAD for cardioversion.

In patients with SHD, propafenone, flecainide, and ibutilide

should be avoided because of the increased risk of proarrhythmia. Instead, amiodarone or dofetilide should be primarily

used in this patient population. In patients with AF present

for more than 7 days, the only AADs with proven efficacy are

dofetilide, amiodarone (oral or IV), and ibutilide. The selection of AAD therapy during this time frame should again be

based on the presence of SHD (Fuster, et al., 2006).

If the practitioner does not wish to proceed with cardioversion, an initial management strategy of ventricular rate

control and anticoagulation is also reasonable. As previously

stated, this strategy, whereby the patient is left in AF, has been

shown to be an acceptable alternative to rhythm control for

the chronic management of AF. The selection of an oral drug

for chronic ventricular rate control is primarily based on the

patient’s LV systolic function. In patients with normal LV

systolic function (LVEF >40%), an oral b-blocker, diltiazem,

or verapamil is preferred over digoxin (Fuster, et al., 2006).

Digoxin can be added if adequate ventricular rate control

cannot be achieved with one of these drugs. In patients with

LVSD (LVEF of 40% or less), an oral b-blocker or digoxin is

preferred because these drugs can also concomitantly be used

to treat chronic HF. The nondihydropyridine CCBs should be

avoided in patients with LVSD because of their potent negative

inotropic effects. In patients with AF and stable HF symptoms

(NYHA class II or III), the b-blockers carvedilol, metoprolol

succinate, or bisoprolol should be used as first-line therapy

because of their documented survival benefits in patients

with HF (CIBIS II Investigators and Committees, 1999;

MERIT-HF Study Group, 1999; Packer, et al., 1996). Other

b-blockers should be avoided in these patients because their

effects on survival in HF are unknown. Digoxin should be used

as first-line therapy in patients with AF and decompensated

HF (NYHA class IV) because b-blocker therapy may exacerbate HF symptoms. For patients with normal or depressed

LV systolic function, oral amiodarone may also be considered

if adequate ventricular rate control cannot be achieved with the

use of b-blockers, nondihydropyridine CCBs, and/or digoxin

(Fuster, et al., 2006). In patients with persistent AF who have

no or acceptable symptoms and stable LV systolic function

(LVEF greater than 40%), the goal heart rate should be less than

110 beats/minute at rest (Van Gelder, et al., 2010; Wann, et al.,

2011). In patients with LVSD (LVEF of 40% or less), a stricter

heart rate goal (less than 80 beats/minute) should be considered

to minimize the potential harmful effects of a rapid heart rate

response on ventricular function (Wann, et al., 2011).

Assessing the patient’s risk of stroke becomes important

for selecting the most appropriate antithrombotic regimen.

The CHADS2 index is recommended for stroke risk stratification in patients with AF (Singer, et al., 2008). With this risk

index, patients with AF are given 2 points if they have a history of a previous stroke or transient ischemic attack and one

point each for being at least 75 years old, having hypertension,

having diabetes, or having congestive HF (CHADS2 is an

acronym for each of these risk factors). The points are added

up, and the total score is then used to determine the most

appropriate antithrombotic therapy for the patient. Patients

with a CHADS2 score of at least 2 are considered to be at high

risk for stroke and should receive warfarin (target INR: 2.5;

range: 2.0 to 3.0). Patients with a CHADS2 score of 1 are considered to be at intermediate risk for stroke and should receive

either warfarin (target INR: 2.5; range: 2.0 to 3.0) or aspirin

75–325 mg/d. However, because of its superior efficacy in

preventing stroke, the use of warfarin is suggested over that

of aspirin in this particular group of patients. Patients with a

CHADS2 score of 0 are considered to be at low risk for stroke

and should receive aspirin 75–325 mg/d. Dabigatran, an

oral direct thrombin inhibitor, can also be considered as an

alternative to warfarin for stroke prevention in patients with

paroxysmal or persistent AF and risk factors for stroke or systemic embolism (Wann, et al., 2011). Patients with prosthetic

heart valves, hemodynamically significant valvular disease, a

creatinine clearance less than 15 mL/minute, or advanced liver

disease are not appropriate candidates for dabigatran therapy.

Please refer to Chapter 54 for a further discussion of anticoagulation in AF.

Antithrombotic therapy should be considered for all

patients regardless of whether a rate-control or rhythm- control

strategy is initiated. In addition, antithrombotic therapy

should be continued if SR is restored because of the potential

for patients to have episodes of recurrent AF.

Third-Line Therapy

For those patients who remain symptomatic despite having

adequate ventricular rate control or for those patients in whom

adequate ventricular rate control cannot be achieved, it is reasonable to consider AAD therapy to maintain SR once they

have been converted to SR. The selection of an AAD to maintain SR is primarily based on the presence of SHD (Wann,

et al., 2011). (See Figure 23-2.) In patients without SHD,

any oral class Ia, Ic, or III AAD can be used to maintain SR.

Arcangelo_Chap23.indd 323 10/8/2011 1:52:29 PM

324 UNIT 4 | PHARMACOTHERAPY FOR CARDIOVASCULAR DISORDERS

However, dronedarone, flecainide, propafenone, or sotalol

should be considered as initial therapy in these patients because

of their less toxic adverse effect profiles. Amiodarone or

dofetilide can be used as alternative therapy if the patient fails

or does not tolerate one of these initial AADs. In patients with

any type of SHD, the class Ic AADs flecainide and propafenone

should be avoided. In these patients, the selection of AAD

therapy is based upon the type of SHD present. In patients

with LVSD (LVEF of 40% or less), either oral amiodarone or

dofetilide can be used. Both dronedarone and sotalol should be

avoided in patients with LVSD because of the risk of increased

mortality (dronedarone) or worsening HF (sotalol). In patients

with coronary artery disease, sotalol, dofetilide, or dronedarone can be used as initial therapy. In these patients, sotalol

and dronedarone should only be used if their LV systolic function is normal. Amiodarone can be considered as an alternative

therapy in these patients if these AADs are not tolerated. In

patients with significant LV hypertrophy, amiodarone is the

drug of choice.

For patients with permanent AF, a treatment strategy of

ventricular rate control and anticoagulation should be used

because the efficacy of AADs is extremely poor in this population. The oral drugs used for ventricular rate control are

discussed in the “Second-Line Therapy” section. Patients with

symptomatic episodes of recurrent AF who fail or do not tolerate at least one class I or III AAD may also be considered for

radiofrequency catheter ablation (Calkins, et al., 2007).

Paroxysmal Supraventricular Tachycardia (Due to

Atrioventricular Nodal Reentrant Tachycardia)

First-Line Therapy

Hemodynamically unstable PSVT requires first-line therapy of

synchronized DCC to restore SR and correct hemodynamic

compromise. Unless contraindicated, patients with mild to

moderate symptoms can be initially managed with vagal

maneuvers (e.g., unilateral carotid sinus massage, Valsalva

maneuver, facial immersion in ice water, and coughing).

Figure 23-3 illustrates an algorithm for the management of

PSVT due to AV nodal reentrant tachycardia.

Second-Line Therapy

If vagal maneuvers are unsuccessful or if PSVT recurs after successful vagal maneuvers, second-line therapy is AADs. The drug

of choice for PSVT is adenosine (American Heart Association,

2010). Clinical studies have shown that adenosine is as effective as IV verapamil in initial conversion of PSVT. Adenosine

does not produce hypotension to the degree that verapamil

does, and it has a shorter half-life. If a total of 30 mg of adenosine does not successfully terminate PSVT, further doses of this

agent are unlikely to be effective. Therefore, in patients with

persistent PSVT, other AADs will need to be used. In these

patients, IV diltiazem, verapamil, or a b-blocker can be used.

If PSVT continues despite these treatment measures, the use

of IV procainamide (LVEF >40%) or amiodarone (normal or

depressed LVEF) can also be considered.

Third-Line Therapy

Third-line therapy focuses on the management of chronic

PSVT. Chronic preventive therapy is usually necessary if the

patient has either frequent episodes of PSVT that require

therapeutic intervention or infrequent episodes of PSVT that

are accompanied by severe symptoms. Radiofrequency catheter ablation is considered first-line therapy for most of these

patients because of its effectiveness in preventing recurrence of

PSVT and its relatively low complication rate. Drug therapy

with oral diltiazem, verapamil, b-blockers, or digoxin can also

be considered if the patient is not a candidate for or refuses to

undergo radio-frequency catheter ablation.

Premature Ventricular Contractions

Occasional PVCs occur in most people and rarely compromise cardiac output or function. Correcting reversible causes

such as an electrolyte imbalance sometimes eliminates these

benign PVCs. Asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic

PVCs in patients without associated heart disease carry little

or no risk. PVCs in patients with heart disease were traditionally treated in the past. Decreasing the number and frequency

of PVCs was thought to diminish the risk of sudden cardiac

death. However, the results of the CAST showed that the use

of AADs to suppress asymptomatic PVCs in patients after

MI may increase mortality rates (CAST Investigators, 1989).

Therefore, if patients with SHD have symptomatic PVCs,

drug therapy should be limited to b-blockers. These agents

have been associated with a reduction in mortality and sudden

cardiac death in post-MI patients. These agents are also effective for suppressing symptomatic PVCs in patients without

SHD. Asymptomatic PVCs do not require treatment.

Nonsustained Ventricular Tachycardia

Ventricular tachycardia that spontaneously terminates within

30 seconds is known as nonsustained VT. Given the poor survival of patients who experience cardiac arrest, it is essential to

identify the most effective treatment strategies to prevent the

initial episode of sustained VT or sudden cardiac death from

occurring.

The presence of nonsustained VT in patients without

SHD is not associated with an increased risk of sudden cardiac death. Therefore, drug therapy is not necessary in these

patients if they are asymptomatic. However, if these patients

do become symptomatic, b-blocker therapy can be initiated.

Post-MI patients (especially those with LVSD) who develop

nonsustained VT are at increased risk for sudden cardiac

death. For these patients, the selection of therapy is based on

the patient’s LV systolic function. In post-MI patients with

an LVEF greater than 35%, drug therapy is not necessary to

treat the arrhythmia if they are asymptomatic. However, these

patients should still chronically receive a b-blocker specifically

to reduce mortality associated with the MI. b-blockers are also

effective if these patients develop significant symptoms associated with the nonsustained VT. In post-MI patients with

an LVEF of 35% or less, electrophysiologic testing is often

Arcangelo_Chap23.indd 324 10/8/2011 1:52:29 PM

CHAPTER 23 | ARRHYTHMIAS 325

performed when asymptomatic nonsustained VT occurs

(Moss, et al., 1996; Buxton, et al., 1999). If sustained VT or

VF is induced, an ICD is then recommended (Epstein, et al.,

2008). In these patients, implantation of the ICD should be

delayed until more than 40 days have elapsed since the MI

occurred. If sustained VT or VF is not induced, a b-blocker

or amiodarone can be initiated.

Sustained Ventricular Tachycardia

VT that persists for at least 30 seconds or that requires electrical or pharmacologic termination because of hemodynamic

instability is known as sustained VT. Since sustained VT can

degenerate into VF, the treatment goals are to terminate the

VT acutely and then prevent recurrence of the arrhythmia.

First-Line Therapy

If the patient is hemodynamically unstable (i.e., severe hypotension, syncope, HF, or angina), immediate synchronized DCC

is first-line therapy. If the patient is hemodynamically stable,

IV amiodarone, IV procainamide, or IV sotalol can be considered (American Heart Association, 2010). Lidocaine can be

used as alternative therapy. Synchronized DCC should be considered if AAD therapy fails.

Second-Line Therapy

Once the acute episode is terminated, measures should be

taken to prevent recurrent episodes of VT. Based on the results

of several trials, ICDs are clearly indicated as first-line therapy in patients with a history of sustained VT or VF (AVID

Investigators, 1997; Connolly, et al., 2000; Kuck, et al., 2000,

Epstein, et al., 2008). If the patient with an ICD experiences

frequent discharges because of recurrent ventricular arrhythmias or new-onset supraventricular arrhythmias (e.g., AF),

either amiodarone and a b-blocker or sotalol monotherapy

can be used. For the patient who refuses or is not a candidate

for an ICD, oral amiodarone should be used as an alternative

therapy.

Pulseless Ventricular Tachycardia/

Ventricular Fibrillation

The majority of cases of sudden cardiac death can be attributed

to VF. Sustained VT usually precedes VF and most commonly

occurs in patients with ischemic heart disease. VF is usually

not preceded by any symptoms and always results in a loss of

consciousness and eventually death if not treated. Immediate

treatment is essential in patients who develop VF or pulseless

VT, since survival is reduced by 10% for every minute that the

patient remains in the arrhythmia. It is imperative to identify

and correct any potential reversible causes for the arrhythmia.

For administration of drug therapy during an episode of

pulseless VT/VF, while IV access is preferred, the guidelines

recommend the intraosseous (IO) route as an alternative if

IV access cannot be established (American Heart Association,

2010). IO access can be used not only for administration of

drugs and fluids, but also for obtaining blood for laboratory

monitoring. If neither IV nor IO access can be established, the

endotracheal route can then be used for the administration of

only certain agents (i.e., atropine, lidocaine, epinephrine, and

vasopressin). Figure 23-4 illustrates an algorithm for the management of pulseless VT/VF.

First-Line Therapy

In patients with pulseless VT/VF, high-quality cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) should be immediately initiated

until a defibrillator or automated external defibrillator (AED)

arrives (American Heart Association, 2010). High-quality

CPR is considered to be delivery of at least 100 compressions

per minute, with the depth of chest compressions being at

least 2 inches. Each cycle of CPR involves delivering 30 chest

compressions followed by two breaths. If a defibrillator or

AED is not readily available, hands-only CPR (compressions

only; no ventilations) should be provided if the bystander possesses no CPR training or is trained but lacks confidence in

providing effective CPR with rescue breaths. If the bystander

possesses CPR training and is confident in their ability to provide effective CPR with rescue breaths, conventional cycles of

CPR (30 chest compressions followed by two breaths) should

be delivered until a defibrillator or AED becomes available.

Once an advanced airway (e.g., endotracheal tube) is placed,

chest compressions should be delivered continuously at a rate

of 100 compressions per minute without pausing for ventilation (should be provided by a separate individual at a rate of

one breath every 6 to 8 seconds). Once a defibrillator or AED

arrives, defibrillation should be administered immediately.

With regard to defibrillation, delivery of only one shock

at a time is recommended in patients with pulseless VT/VF

to minimize interruptions in chest compressions (American

Heart Association, 2010). For biphasic defibrillators, the dose

of the shock is device-specific (usually 120 to 200 J); the

maximum dose available can be used for the initial shock if

the effective dose range of the defibrillator is unknown. This

dose or a higher dose can then be used for any subsequent

shocks that may be needed. After delivery of the initial shock

in patients with pulseless VT/VF, CPR should be immediately resumed and continued for 2 minutes, after which the

patient’s pulse and rhythm should be checked. Delaying

pulse and rhythm checks until after this period of CPR is

administered is intended to minimize interruptions in chest

compressions and increase the potential for success with defibrillation. If pulseless VT/VF persists, another shock should

be delivered at the appropriate dose, followed by 2 minutes

of CPR. This general sequence of resuscitation and defibrillation should be followed for as long as the patient remains in

pulseless VT/VF.

Second-Line Therapy

If pulseless VT/VF persists after delivery of at least one shock

and CPR, vasopressor therapy with either epinephrine or

vasopressin should be initiated (American Heart Association,

2010). One dose of vasopressin may be given to replace either

the first or second dose of epinephrine. Vasopressin’s half-life

Arcangelo_Chap23.indd 325 10/8/2011 1:52:29 PM

326 UNIT 4 | PHARMACOTHERAPY FOR CARDIOVASCULAR DISORDERS

of approximately 10 to 20 minutes is considerably longer than

the 3- to 5-minute half-life of epinephrine, which suggests that

its vasopressor effects may be more sustained than those of epinephrine during cardiac arrest. Unlike epinephrine, vasopressin also maintains its vasoconstrictive effects under acidotic

and hypoxic conditions, which suggests that this agent may

continue to work during prolonged cardiac arrest situations.

The recommended dosage of epinephrine for pulseless VT/

VF is 1 mg given IV push/IO every 3 to 5 minutes throughout the duration of the pulseless VT/VF episode. The recommended dosage of vasopressin for pulseless VT/VF is 40 units

IV push/IO for one dose only.

Third-Line Therapy

If pulseless VT/VF persists despite the use of defibrillation, CPR, and vasopressor therapy, AAD therapy can be

considered. IV amiodarone is recommended as first-line AAD

therapy for the treatment of pulseless VT/VF (American Heart

Association, 2010). This agent has been shown to be safe and

effective in the management of both in-hospital and outof-hospital pulseless VT/VF (Dorian, et al., 2002; Kudenchuck,

et al., 1999). Compared to lidocaine, IV amiodarone has been

associated with a significantly higher rate of survival to hospital

admission in patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest due to VF

(Dorian, et al., 2002). Therefore, lidocaine should only be considered for the treatment of pulseless VT/VF if IV amiodarone is not

available (American Heart Association, 2010). IV procainamide

is no longer recommended for pulseless VT/VF. IV magnesium

sulfate can be considered if TdP is present or suspected.

If the patient is resuscitated from the pulseless VT/VF episode, measures should be taken to prevent recurrent episodes

of cardiac arrest. Based on the results of several trials, ICDs are

clearly indicated as first-line therapy in patients with a history

of sustained VT or VF (AVID Investigators, 1997; Connolly,

et al., 2000; Kuck, et al., 2000; Epstein, et al., 2008). If patients

with an ICD experience frequent discharges because of recurrent ventricular arrhythmias or new-onset supraventricular

arrhythmias (e.g., AF), either amiodarone and a b-blocker or

sotalol monotherapy can be used. For patients who refuse or

are not candidates for an ICD, oral amiodarone should be used

as an alternative therapy.

Bradycardia

If patients with bradycardia present with signs and symptoms

of adequate perfusion, only close observation is required. If

patients with bradycardia develop signs or symptoms of poor

perfusion (e.g., altered mental status, chest pain, hypotension, shock), IV atropine (0.5 mg every 3 to 5 minutes, up to

3 mg total dose) should be immediately administered

(American Heart Association, 2010). If atropine is not effective, either transcutaneous pacing or a continuous infusion of

a sympathomimetic agent, such as dopamine (2 to 10 mcg/

kg/min) or epinephrine (2 to 10 mcg/min) (i.e., dopamine

or epinephrine) should be initiated. If symptomatic bradycardia persists despite any of these measures, transvenous pacing

should be utilized. Figure 23-5 illustrates an algorithm for the

management of bradycardia.

Special Population Considerations

Pediatric

The epidemiology of arrhythmias is different between adults

and children. Adults have arrhythmias primarily of a cardiac

origin, whereas children have arrhythmias primarily of a respiratory origin.

Tachyarrhythmias occasionally compromise infants and

young children. PSVT is the most common arrhythmia in young

children. It typically occurs during infancy or in children with

congenital heart disease. PSVT with ventricular rates exceeding

180 to 220 beats/minute can produce signs of shock. If signs

of shock appear, synchronized cardioversion or administration

of adenosine can be done in an emergency. Common causes of

PSVT in young children and infants are congenital heart disease (preoperative) such as Ebstein’s anomaly, transposition of

the great arteries, or a single ventricle. Postoperative PSVT also

can occur after atrial surgery for correction of congenital defects

of the heart. Other common causes of PSVT in children are

drugs such as sympathomimetics (cold medications, theophylline, b-agonists). WPW syndrome and hyperthyroidism also

can cause PSVT. Common causes of AF and atrial flutter in

children are intra-atrial surgery, Ebstein’s anomaly, heart disease

with dilated atria (aortic valve regurgitation), cardiomyopathy,

WPW syndrome, sick sinus syndrome, and myocarditis.

Bradycardia is a common arrhythmia in seriously ill

infants or children. It is usually associated with a fall in cardiac

output and is an ominous sign, suggesting that cardiac arrest is

imminent. The first-line therapy for this arrhythmia in infants

and young children is administration of oxygen, support respiration, epinephrine and, possibly, atropine.

Pulseless VT and VF are treated much the same way as

in adults; however, vasopressin is not currently recommended

for children (American Heart Association, 2010). The recommended dose of epinephrine for a child with pulseless VT/VF

is 0.01 mg/kg IV/IO, administered as 0.1 mL/kg of a 1:10,000

dilution. If IV/IO access cannot be established, epinephrine

can be administered endotracheally (0.1 mg/kg administered

as 0.1 mL/kg of a 1:1,000 dilution).

Geriatric

With aging, body fat increases, lean body tissue decreases, and

hepatic and renal system changes set the stage for potential overdosage and toxicity, particularly in the case of AADs. Similarly,

declining function affects the amount and dosage of the drug

prescribed as well as the occurrence of adverse effects. Cardiac

disease and chronic conditions such as HF exacerbate the decline

in organ function. Together, these factors can increase the risk of

an adverse effect from the AADs the practitioner prescribes.

For example, digoxin toxicity is relatively common in

elderly patients who are not receiving a reduced dosage to

accommodate for the reduced renal function. The practitioner

must always assess the patient’s baseline renal function (to identify abnormalities in the blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine) and baseline hepatic function (to identify impairment in

liver function). These two tests are important in prescribing the

proper dosage of many of the AADs discussed in this chapter.

Arcangelo_Chap23.indd 326 10/8/2011 1:52:30 PM

CHAPTER 23 | ARRHYTHMIAS 327

Signs and symptoms of adverse effects of many drugs are

confusion, weakness, and lethargy. These signs and symptoms

are often attributed to senility or disease. Therefore, it is important for the practitioner to take a thorough drug history and to

document accurately the dosages and frequencies prescribed in

the patient record. If the practitioner merely attributes confusion to old age, the patient may continue to receive the drug

while actually experiencing drug toxicity. Furthermore, the

practitioner may add another drug to treat the complications

caused by the original AAD, compounding the issue of polypharmacy and excessive medication.

In elderly patients taking AADs, the practitioner must

be particularly alert to adverse effects from diuretics, digoxin,

sleeping aids, and nonprescription drugs.

AADs sometimes require accurate and timely dosing. If

an elderly patient forgets to take a dose or cannot remember

when he or she took the last dose, undermedication or overmedication may occur. This can be dangerous when AADs are

prescribed. Many of the elderly have multiple prescriptions,

even for the same medication, and therefore take an overdose

of the drug. Consequently, it is essential to review medications

with elderly patients and make sure they understand and can

follow a safe drug therapy regimen.

MONITORING PATIENT RESPONSE

The goals of AAD therapy are to restore SR and prevent

recurrences of the original arrhythmia or development of

new arrhythmias. Evaluating the outcomes of AAD therapy

requires the practitioner to schedule regular follow-up visits

after initial treatment of the arrhythmia. The outcomes to be

closely monitored include impulse generation and conduction

from the SA node to the AV node, time interval for conduction, heart rate within a normal range that is age-specific, and

patterns of AV and ventricular conduction.

Data to be monitored to evaluate therapeutic outcomes vary

from the simple to complex. The patient may monitor some of

them and needs to be taught the signs and symptoms to look for

and the expectations from the therapeutic regimen. Patients with

arrhythmias may be monitored on a regular or periodic basis with

12-lead ECG, 24-hour Holter monitors, electrophysiologic testing, monitoring of vital signs (blood pressure, pulse rate), echocardiograms for cardiac function, electrolytes, and serum drug levels.

In addition, the patient needs to self-monitor for symptoms such as lightheadedness, dizziness, syncopal episodes,

palpitations, chest pain, shortness of breath, or weight gain.

Other clinical outcomes to be monitored are those that affect

quality of life, such as activity tolerance, organ perfusion, cognitive function, fear, anxiety, and depression.

PATIENT EDUCATION

Drug Information

Included in the therapeutic plan for arrhythmia is patient education. Learning outcomes can be evaluated by monitoring

compliance with the medication regimen, recurrences of

arrhythmia, adverse effects, weight gain, blood pressure, heart

rate, and emergency department visits or hospitalizations.

AADs have narrow therapeutic windows. Toxicity is common at normal dosages. Consequently, patient education is

essential for providing maximal benefits and avoiding adverse

effects and accidental overdosing or underdosing.

The patient, family, and significant others should be taught

the basics, such as the name of the drug (both the generic and

trade name), the dose, the frequency and timing of the dose,

and the reason the drug is needed. This may avoid duplicate

prescribing and administration of AADs. The patient should

communicate, either verbally or in writing, the names and dosages of these drugs to all other health care providers and should

wear a medical identification device listing all medications. In

addition, the patient should inform his or her health care provider when any new prescription, over-the-counter, or complementary or alternative medications are started so that potential

drug interactions can be minimized or avoided.

The practitioner should provide written instructions for the

medication regimen. Providing instructions in large print and

simple language may be helpful to patients who have difficulty

with memory, hearing, or vision. Instructions should include

what to do when the patient misses a dose of medication, has an

adverse response to the medication, or wants to stop taking the

drug. If b-blockers are prescribed, the patient should be warned

that abrupt discontinuation may result in rebound angina, an

increased heart rate, and hypertension. The symptoms associated with these adverse effects also should be identified.

The practitioner can also teach the patient or caregiver

how to take blood pressure and pulse readings, how to interpret the readings, and how to recognize and respond to signs

and symptoms of hypotension, dizziness, chest pain, shortness of breath, peripheral edema, or palpitations. The patient

should take his or her weight each day and call the practitioner

if weight gain of over 2 pounds occurs. If the patient has difficulty learning these monitoring techniques or cannot perform them, he or she may need to schedule regular follow-up

appointments for monitoring. Patients with AF or atrial flutter

should know the signs and symptoms of a stroke.

In today’s health care environment, the insurance plan’s

pharmacy provider sometimes makes substitutions with generics or less expensive brands of medications. To prevent harmful drug effects, the patient needs to be aware of this practice

and should be cautioned not to change brands of the prescribed

AAD or anticoagulant without the approval of the practitioner.

An important teaching point from an ethical and legal

perspective is to warn the patient to avoid hazardous activities

such as driving, using electrical tools, climbing ladders, or any

activity that would put the patient or others in harm’s way

until the effects of the drug are demonstrated. Patients with

an ICD should refrain from driving for at least 6 months after

either implantation of the device or an appropriate discharge

from the device for a ventricular arrhythmia. Documentation

of patient teaching on risks, benefits, lifestyle modification, and

safety issues with AAD treatment should always be entered in

Arcangelo_Chap23.indd 327 10/8/2011 1:52:30 PM

328 UNIT 4 | PHARMACOTHERAPY FOR CARDIOVASCULAR DISORDERS

the patient’s record. Documenting a review of this information

on a follow-up visit aids health care providers who follow up

on the patient’s progress in the future.

Nutrition

Clear instructions should be given to avoid alcohol, excessive

salt intake, and caffeine during treatment for arrhythmias.

Many AADs may cause periods of hypotension resulting in

dizziness, or the dose of the drug may need to be regulated,

especially in the initial weeks.

Complementary and Alternative Medications

The practitioner must emphasize to the patient the importance

of reporting the use of any of these agents so that interactions

with AAD therapy can be minimized or avoided. While the

information regarding potential interactions between AADs

and specific complementary and alternative medications is

relatively sparse, there are a few notable interactions of which

practitioners should be aware. Patients taking AADs should

avoid licorice root. Licorice has mineralocorticoid effects,

which can promote hypokalemia. In patients taking digoxin,

the presence of hypokalemia may predispose the patient to

digoxin toxicity. In patients taking other AADs, the presence

of hypokalemia may promote the development of atrial or ventricular arrhythmias. In addition, certain licorice preparations

have been shown to cause a prolonged QT interval, which

may be additive in patients receiving class Ia or III AADs. This

interaction could lead to TdP. The use of Siberian ginseng or

oleander should also be avoided in patients receiving digoxin,

as digoxin toxicity may result. The use of St. John’s wort may

decrease digoxin concentrations; therefore, digoxin concentrations should be closely monitored when concomitant therapy

is used. St. John’s wort may also decrease plasma concentrations of amiodarone and dronedarone, which may predispose

the patient to arrhythmia recurrence. Consequently, the use

of St. John’s wort in patients receiving amiodarone or dronedarone should be avoided. Patients with a history of atrial or

ventricular arrhythmias should also be instructed to avoid the

use of any medication containing ephedra (e.g., Ma Huang)

because it can promote the development of arrhythmias.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

*Starred references are cited in the text.

*2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care science. (2010). Circulation,

122(Suppl 3), S1–S933.

*The Atrial Fibrillation Follow-up Investigation of Rhythm Management

(AFFIRM) Investigators. (2002). A comparison of rate control and

rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillation. New England Journal of

Medicine, 347, 1825–1833.

*Anderson, J. L., Lutz, J. R., & Allison, S. B. (1983). Electrophysiologic and

antiarrhythmic effects of oral flecainide in patients with inducible ventricular tachycardia. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 2, 105–114.

*Antiarrhythmics Versus Implantable Defibrillators (AVID) Investigators

(1997). A comparison of antiarrhythmic-drug therapy with implantable

defibrillators in patients resuscitated from near-fatal ventricular arrhythmias. New England Journal of Medicine, 337, 1576–1583.

*Bardy, G. H., Lee, K. L., Mark, D. B., et al. (2005). Amiodarone or an

implantable cardioverter-defibrillator for congestive heart failure. New

England Journal of Medicine, 352, 225–237.

*Buchanan, L. V., Turcotte, U. M., Kabell, G. G., & Gibson, J. K. (1993).

Antiarrhythmic and electrophysiologic effects of ibutilide in a chronic

canine model of atrial flutter. Journal of Cardiovascular Pharmacology, 33,

10–14.

*Buxton, A. E., Lee, K. L., Fisher, J. D., et al. (1999). A randomized study of

the prevention of sudden death in patients with coronary artery disease.

New England Journal of Medicine, 341, 1882–1890.

Cairns, J. A., Connolly, S. J., & Roberts, R. (1997). Randomized trial

of outcome after myocardial infarction in patients with frequent or

repetitive ventricular premature depolarizations: CAMIAT. Lancet, 349,

675–682.

*Calkins, H., Brugada, J., Packer, D.L., et al. (2007). HRS/EHRA/ECAS

expert consensus statement on catheter and surgical ablation of atrial

fibrillation: Recommendations for personnel, policy, and follow-up.

Heart Rhythm, 4, 816–861.

*Cardiac Suppression Trial Investigators. (1989). Preliminary report: Effect of

encainide and flecainide on mortality in a randomized trial of arrhythmia

suppression after myocardial infarction. New England Journal of Medicine,

321, 406–412.

*Carlsson, J., Miketic, S., Windeler, J., et al. (2004). Randomized trial of

rate-control versus rhythm-control in persistent atrial fibrillation: The

Strategies of Treatment of Atrial Fibrillation (STAF) study. Journal of the

American College of Cardiology, 41, 1690–1696.

*CIBIS II Investigators and Committees. (1999). The Cardiac Insufficiency

Bisoprolol Study II (CIBIS-II): A randomised trial. Lancet, 353, 9–13.

*Connolly, S., Gent, M., Roberts, R. S., et al. (2000). Canadian Implantable

Defibrillator Study (CIDS): A randomized trial of the implantable cardioverter defibrillator versus amiodarone. Circulation, 101, 1297–1302.

*Connolly, S. J., Dorian, P., Roberts, R. S., et al. (2006). Comparison of

beta-blockers, amiodarone plus beta-blockers, or sotalol for prevention

of shocks from implantable cardioverter defibrillators: The OPTIC study.

Journal of the American Medical Association, 295, 165–171.

Dager, W. E., Sanoski, C. A., Wiggins, B. S., & Tisdale, J. E. (2006).

Pharmacotherapy considerations in advanced cardiac life support.

Pharmacotherapy, 26, 1703–1729.

*Dorian, P., Cass, D., Schwartz, B., et al. (2002). Amiodarone as compared

with lidocaine for shock-resistant ventricular fibrillation. New England

Journal of Medicine, 346, 884–890.

*Duff, H. J., Roden, D., & Primm, R. K. (1983). Mexiletine in the treatment of resistant ventricular arrhythmias: Enhancement of efficacy and

reduction of dose-related side effects by combination with quinidine.

Circulation, 67, 1124–1128.

*Epstein, A. E., DiMarco, J. P., Ellenbogen, K. A., et al. (2008). ACC/AHA/

HRS 2008 guidelines for device-based therapy of cardiac rhythm abnormalities: A report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart

Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to

Revise the ACC/AHA/NASPE 2002 Guideline Update for Implantation

of Cardiac Pacemakers and Antiarrhythmia Devices). Journal of the

American College of Cardiology, 51, e1–e62.

*Fuster, V., Rydén, L. E., Cannom, D. S., et al. (2006). ACC/AHA/ESC 2006

guidelines for the management of patients with atrial fibrillation: A report

of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task

Force on Practice Guidelines and the European Society of Cardiology

Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing Committee to Revise the

2001 Guidelines for the Management of Atrial Fibrillation). Journal of the

American College of Cardiology, 48, e149–e246.

*Goldschlager, N., Epstein, A. E., Naccarelli, G., et al. (2007). A practical

guide for clinicians who treat patients with amiodarone. Heart Rhythm, 4,

1250–1259.

*Hohnloser, S. H., Crijns, H. J., van Eickels, M., et al. (2009). Effect of

dronedarone on cardiovascular events in atrial fibrillation. New England

Journal of Medicine, 360, 668–678.

Arcangelo_Chap23.indd 328 10/8/2011 1:52:30 PM

CHAPTER 23 | ARRHYTHMIAS 329

*Hohnloser, S. H., Kuck, K. H., & Lilienthal, J. (2000). Rhythm or rate

control in atrial fibrillation—Pharmacological Intervention in Atrial

Fibrillation (PIAF): A randomised trial. Lancet, 356, 1789–1794.

Julian, D. G., Camm, A. J., & Fragnin, G. (1997). Randomized trial of effect

of amiodarone on mortality inpatients with left ventricular dysfunction

after recent myocardial infarction: EMIAT. Lancet, 349, 667–674.

*Kennedy, H. L., Brooks, M. M., & Barker, A. H. (1994). Beta blocker

therapy in the Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial. American Journal

of Cardiology, 74, 674–680.

*Køber, L., Bloch-Thomsen, P. E., Møller, M., et al. (2000). Danish Investigations

of Arrhythmia and Mortality on Dofetilide (DIAMOND) Study Group.

Effect of dofetilide in patients with recent myocardial infarction and

left-ventricular dysfunction: A randomised trial. Lancet, 356, 2052–2058.

*Køber, L., Torp-Pedersen, C., McMurray, J. J., et al. (2008). Increased mortality after dronedarone therapy for severe heart failure. New England

Journal of Medicine, 358, 2678–2687.

*Kuck, K. H., Cappato, R., Siebels, J., et al. (2000). Randomized comparison

of antiarrhythmic drug therapy with implantable defibrillators in patients

resuscitated from cardiac arrest: The Cardiac Arrest Study Hamburg

(CASH). Circulation, 102, 748–754.

*Kudenchuck, P. J., Cobb, L. A., Copass, M. K., et al. (1999). Amiodarone for

resuscitation after out-of-hospital cardiac arrest due to ventricular fibrillation. New England Journal of Medicine, 341, 871–879.

*Lichstein, E., Morganroth, J., Harrist, R., & Hubble, M. S. (1983). Effect of

propranolol on ventricular arrhythmia: The beta blocker heart attack trial

experience. Circulation, 67 (Suppl. I), 5–10.

*MERIT-HF Study Group (1999). Effect of metoprolol CR/XL in chronic

heart failure: Metoprolol CR/XL Randomized Intervention Trial in

Congestive Heart Failure (MERIT-HF). Lancet, 353, 2001–2007.

*Miller, M. R., McNamara, R. L., Segal, J. B., et al. (2000). Efficacy of agents

for pharmacological conversion of atrial fibrillation and subsequent

maintenance of sinus rhythm: A meta-analysis of clinical trials. Journal of

Family Practice, 49, 1033–1046.

*Moss, A. J., Hall, W. J., Cannom, D. S., et al. (1996). Improved survival with an

implanted defibrillator in patients with coronary disease at high risk for ventricular arrhythmia. New England Journal of Medicine, 335, 1933–1940.

*Moss, A. J., Zareba, W., Hall, W. J., et al. (2002). Prophylactic implantation

of a defibrillator in patients with myocardial infarction and reduced ejection fraction. New England Journal of Medicine, 346, 877–883.

*Opolski, G., Torbicki, A., Kosior, D. A., et al. (2004). Rate control vs

rhythm control in patients with nonvalvular persistent atrial fibrillation:

The results of the Polish How to Treat Chronic Atrial Fibrillation (HOT

CAFE) Study. Chest, 126, 476–486.

*Oral, H., Souza, J. J., Michaud, G. F., et al. (1999). Facilitating transthoracic cardioversion of atrial fibrillation with ibutilide pretreatment.

New England Journal of Medicine, 340, 1849–1854.

*Pacifico, A., Hohnloser, S. H., Williams, J. H., et al. (1999). Prevention

of implantable-defibrillator shocks by treatment with sotalol: Sotalol

Implantable Cardioverter-Defibrillator Study Group. New England

Journal of Medicine, 340, 1855–1862.

*Packer, M., Bristow, M. R., Cohn, J. N., et al. (1996). The effect of carvedilol on morbidity and mortality in patients with chronic heart failure.

New England Journal of Medicine, 334, 1349–1355.

*Phillips, B. G., Gandhi, A. J., Sanoski, C. A., et al. (1997). Comparison

of intravenous diltiazem and verapamil for the acute treatment of atrial

fibrillation and flutter. Pharmacotherapy, 17, 1238–1245.

*Roy, D., Talajic, M., Dorian, P., et al. (2000). Amiodarone to prevent recurrence

of atrial fibrillation. New England Journal of Medicine, 342, 913–920.

*Roy, D., Talajic, M., Nattel, S., et al. (2008). Rhythm control versus rate

control for atrial fibrillation and heart failure. New England Journal of

Medicine, 358, 2667–2677.

*Sanoski, C. A., & Bauman, J. L. (2002). Clinical observations with the

amiodarone/warfarin interaction: Dosing relationships with long-term

therapy. Chest, 121, 19–23.

*Singer, D. E., Albers, G. W., Dalen, J. E., et al. (2008). Antithrombotic therapy

in atrial fibrillation: American College of Chest Physicians Evidence-Based

Clinical Practice Guidelines (8th ed.). Chest, 133, 546S–592S.

*Singh, B. N., Connolly, S. J., Crijns, H. J., et al. (2007). Dronedarone for

maintenance of sinus rhythm in atrial fibrillation or flutter. New England

Journal of Medicine, 357, 987–999.

*Singh, S., Zoble, R. G., Yellen, L., et al. (2000). Efficacy and safety of oral

dofetilide in converting to and maintaining sinus rhythm in patients

with chronic atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter: The Symptomatic Atrial

Fibrillation Investigative Research on Dofetilide (SAFIRE-D) Study.

Circulation, 102, 2385–2390.

*Slavik, R. S., Tisdale, J. E., & Borzak, S. (2001). Pharmacological conversion

of atrial fibrillation: A systematic review of available evidence. Progress in

Cardiovascular Diseases, 44, 121–152.

*Stambler, B. S., Wood, M. A., Ellenbogen, K. A., et al. (1996). Efficacy and

safety of repeated intravenous doses of ibutilide for rapid conversion of

atrial flutter or fibrillation. Circulation, 94, 1613–1621.

Stroke Prevention in Atrial Fibrillation Investigators. (1991). Stroke prevention in atrial fibrillation study: Final report. Circulation, 84, 527–539.

*Teo, K. K., Yusuf, S., & Furberg, C. D. (1993). Effects of prophylactic antiarrhythmic drug therapy in acute myocardial infarction: An overview of

results from randomized controlled trials. Journal of the American Medical

Association, 270, 1589–1595.

*Van Gelder, I. C., Groenveld, H. F., Crijns H. J. G. M., et al. (2010). Lenient

versus strict rate control in patients with atrial fibrillation. New England

Journal of Medicine, 362, 1363–1373.

*Van Gelder, I. C., Hagens, V. E., Bosker, H. A., et al. (2002). The Rate

Control Versus Electrical Cardioversion for Persistent Atrial Fibrillation

Study Group. A comparison of rate control and rhythm control in

patients with recurrent persistent atrial fibrillation. New England Journal

of Medicine, 347, 1834–1840.

*Vaughan Williams, E. M. (1984). A classification of antiarrhythmic actions

reassessed after a decade of new drugs. Journal of Clinical Pharmacology,

24, 129–147.

*Volgman, A. S., Winkel, E. M., Pinski, S. L., et al. (1998). Conversion

efficacy and safety of intravenous ibutilide compared with intravenous

procainamide in patients with atrial flutter or fibrillation. Journal of the

American College of Cardiology, 31, 1414–1419.

*Vukmir, R. B., & Stein, K. L. (1991). Torsades de pointes therapy with phenytoin. Annals of Emergency Medicine, 20, 198–200.

*Wann, L. S., Curtis, A. B., Ellenbogen, K. A., et al. (2011). 2011 ACCF/

AHA/HRS focused update on the management of patients with atrial

fibrillation (update on dabigatran): A report of the American College

of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on

Practice Guidelines. Circulation, 123, 1144–1150.

*Wann, L. S., Curtis, A. B., January, C. T., et al. (2011). 2011 ACCF/AHA/

HRS focused update on the management of patients with atrial fibrillation (updating the 2006 guidelines): A report of the American College

of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on

Practice Guidelines. Circulation, 123, 104–123.

*Wit, A. L., Rosen, M. R., & Hoffman, B. F. (1974). Electrophysiology

and pharmacology of cardiac arrhythmias: Relationship of normal and

abnormal electrical activity of cardiac fibers to the genesis of arrhythmias.

American Heart Journal, 88, 664–670, 798–806.

*Wyse, D. G., Kellen, J., & Rademaker, A. W. (1988). Prophylactic versus

selective lidocaine for early ventricular arrhythmias of myocardial infarction. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 12, 507–513.

*Wyse, D. G., Waldo, A. L., DiMarco, J. P., et al. (2002). A comparison of

rate control and rhythm control in patients with atrial fibrillation. New

England Journal of Medicine, 347, 1825–1833.

Zipes, D. P., Camm, A. J., Borggrefe, M., et al. (2006). ACC/AHA/ESC 2006

guidelines for management of patients with ventricular arrhythmias and

the prevention of sudden cardiac death: A report of the American College

of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force and the European

Society of Cardiology Committee for Practice Guidelines (Writing

Committee to Develop Guidelines for Management of Patients with

Ventricular Arrhythmias and the Prevention of Sudden Cardiac Death).

Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 48, e247–e346.

Arcangelo_Chap23.indd 329 10/8/2011 1:52:30 PM

Arcangelo_Chap23.indd 330 10/8/2011 1:52:30 PM

5 UNIT

Pharmacotherapy

for Respiratory

Disorders

Arcangelo_Chap24.indd 331 10/8/2011 1:52:50 PM

CHAPTER

332

Virginia P. Arcangelo

fall and spring, and coronavirus (10% to 15%), which is most

prevalent during the winter. The respiratory syncytial virus,

influenza virus, parainfluenza virus, and adenovirus are also

responsible, but the rhinovirus is the single most pervasive

cause of colds. The rhinovirus is a single-stranded ribonucleic

acid virus that replicates well at 95°F (35°C) or below but

poorly at 99 to 100°F (37.2 to 37.8°C), which is probably

why it causes URIs and not pneumonia.

Predisposition to viral infections can be attributed to many

factors, including frequent exposure to viral infectious agents;

in children, the age of the child; and the inability to resist

invading organisms because of allergies, malnutrition, immune

deficiencies, physical abnormalities, or other comorbid conditions. Some experts propose a relationship between the host

response to the virus and the production of cold symptoms.

Studies show that common colds are more frequent or more

severe in those under increased stress, probably as a result of

stress weakening the immune system.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

If the protective barriers of the upper respiratory tract (i.e., cough,

gag, and sneeze reflexes, lymph nodes, immunoglobulin [Ig] A

antibodies, and rich vasculature) fail, viral pathogens trigger an

acute inflammatory reaction with release of vasoactive mediators

and increased parasympathetic stimuli. This produces congestion and rhinorrhea. Rhinoviruses grow in the upper airway, and

attach and gain entry to host cells by binding to an intracellular

adhesion molecule. Infection begins in the adenoidal area and

spreads to the ciliated epithelium in the nose. Rhinoviruses are

hardy and remain infectious for at least 3 hours after drying on

hard surfaces such as telephones or countertops, but they do not

last as long on porous surfaces such as tissues.

Transmission of the virus has been attributed to three

methods: airborne transmission by small particles (droplets),

airborne transmission by large particles, and direct contact.

Large particle transmission is not efficient and requires prolonged exposure. The major means of transmission is by direct

contact from a donor’s nose to a donor’s hand, and from

there to the recipient’s hand and subsequently to the nose or

eye. Although conjunctival cells are not thought to harbor

Upper Respiratory Infections

Upper respiratory tract infections (URIs), including the common

cold and sinusitis, are some of the most common problems seen

in primary care. URIs are usually self-limiting, minor illnesses

that account for half or more of all acute illnesses. It is difficult

to differentiate the common cold from sinusitis or allergic rhinitis. (See Chapter 47.) URIs share common symptoms, such as

nasal discharge, nasal congestion, tenderness over the sinuses,

fever, headache, malaise, sore throat and myalgias, sneezing, a

full feeling around the eyes and ears, and coughing. Symptoms

may present individually or in combination, and it is difficult to

determine whether the cause is viral or bacterial.

URIs can progress to acute or chronic complications. In

children especially, URIs may progress to otitis media. In 5%

to 10% of cases, the viral or bacterial cause may travel, causing sinusitis and bronchitis. There is an enormous economic

burden associated with URIs.

COMMON COLD

Acute infectious rhinitis (coryza), or the common cold, is a viral

URI. One of the most common infections, it is self-limiting.

Coryza is an acute inflammation of the mucous membranes of the

respiratory passages, particularly of the nose, sinuses, and throat,

and is characterized by sneezing, rhinorrhea (watery nasal discharge), and coughing. The common cold has a short duration.

Approximately 100 million colds occur annually in the

United States, resulting in approximately 26 million days off from

school, 23 million absent days from work, 27 million visits to a

primary care provider, and 250 million days of restricted activities. Nearly $1 billion is spent on cold remedies and $1.5 billion

on analgesics. Adults average three colds per year. Children average six episodes per year, and the common cold is more common

in children who attend day care or preschool (where they are in

contact with other children and groups that may spread disease)

than in those who spend more time at home and have less contact

with crowds. Exposure to smoke is also a predisposing factor.

CAUSES

The pathogens most frequently associated with common colds

are rhinovirus (30% to 40% of cases), especially during the

24

Arcangelo_Chap24.indd 332 10/8/2011 1:52:50 PM

CHAPTER 24 | UPPER RESPIRATORY INFECTIONS 333

rhinovirus, it probably can be passed through the tear duct

into the nose. Incubation of the rhinovirus is 1 to 10 days.

Onset of signs and symptoms occurs 1 to 2 days after viral

infection, and they peak in approximately 2 to 4 days. The

virus may remain present for a week or longer after the onset of

symptoms. A cough may persist after other symptoms resolve.

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA

Diagnostic tests have no cost/benefit effect in diagnosing the

common cold. Symptoms consist primarily of clear nasal discharge, sneezing, nasal congestion, cough, low-grade fever (below

102°F [38.9°C]), scratchy or sore throat, mild aches, chills,

headache, watery eyes, tenderness around the eyes, full feeling

in the ears, and fatigue. In children, the presentation could also

include nasal blockage, fever with seizures, anorexia, vomiting,

diarrhea, and abdominal pain. Symptoms usually resolve in

approximately 1 week, but they may linger for 2 weeks.

INITIATING DRUG THERAPY

Mistreatment of the common cold by clinicians is common

for two reasons:

• It is difficult to determine whether the cause is viral or

bacterial.

• Patients often have preconceived notions and demand antibiotics for their URI even though it is simply the common

cold, which is caused by a virus.

There is no cure for the common cold. Treatment is geared

toward minimizing symptoms (Table 24.1).

Nonpharmacologic alternatives to treating the common

cold are the first line of treatment. For example, rest allows the

body to gain strength and be more effective in defending itself

against the pathogen. The body can then dictate the increase

in activities. An alternative to decongestants and expectorants

is increasing water or juice intake. This assists in liquefying

tenacious secretions, making expectoration easier, soothing

scratchy, sore throats, and relieving dry skin and lips. Saline

gargles also are effective for soothing sore throats.

Coughing caused by chest congestion can cause a muscular chest pain. Menthol rubs can soothe this ache and open

airways for some congestion relief. Menthol lozenges also have

been effective in soothing scratchy throats and clearing nasal

passages. Saline nasal flushes are also effective for clearing nasal

passages without the rebound side effect. Petrolatum-based

ointments for raw and macerated skin around the nose and

upper lip ease the drying effects of dehydration and the use of

multiple tissues. (See Table 24.1.)

Other measures, such as drinking chicken soup, taking

a hot shower, or using a room humidifier, may prove helpful.

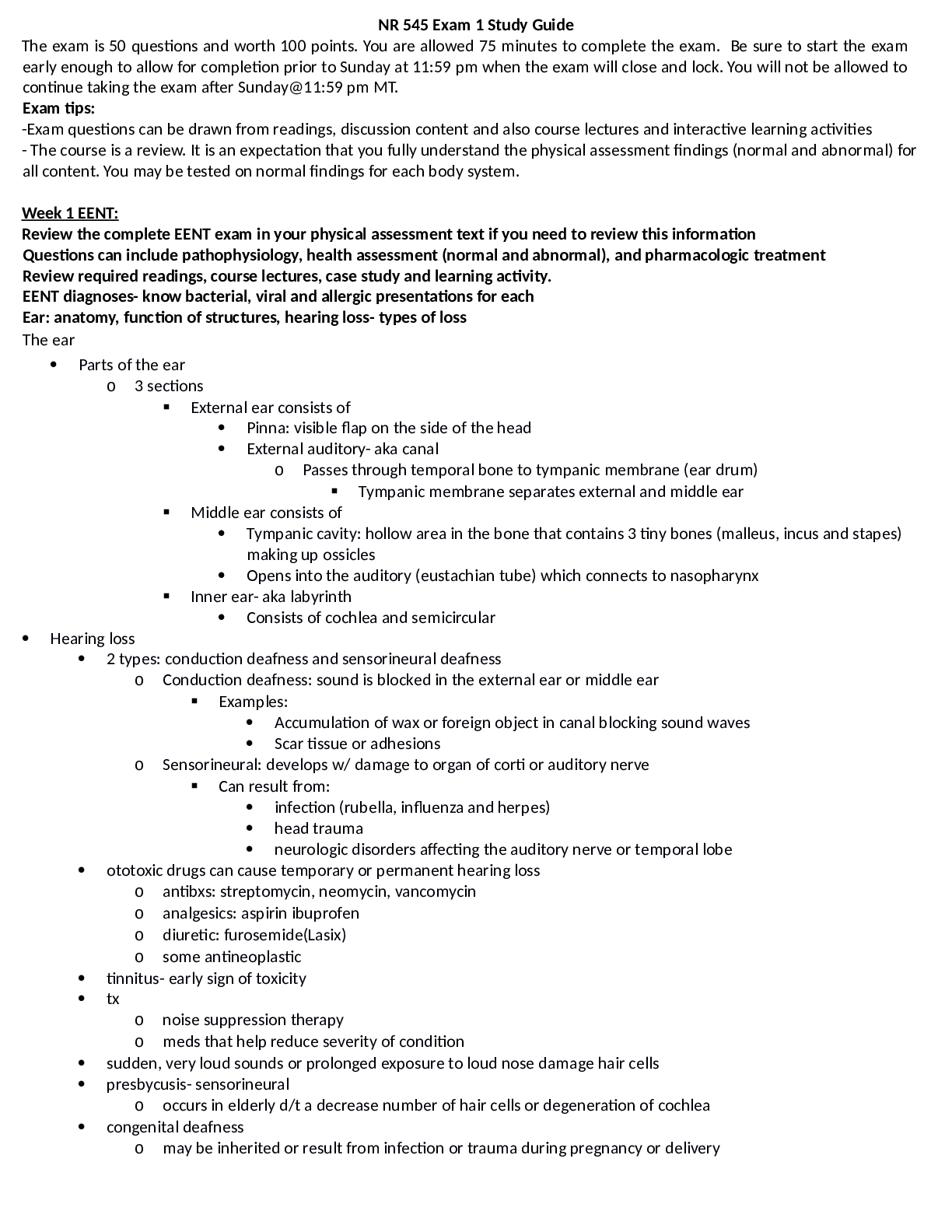

TABLE 24.1 Alternative Therapies for Cold Symptoms

Symptoms Nonpharmacologic Pharmacologic Alternative Therapy

Any cold symptoms Eat proper diet, rest, drink fluids. Echinacea (prevention)

Zinc lozenges (decreased

duration of symptoms)

Rhinorrhea Use disposable paper tissues. Anticholinergic nasal spray

Nasal obstruction Decrease ingestion of milk

products.

Children: saline nose drops by bulb

syringe

Bayberry tea

Inhale warm, moist heat, such as

showers.

Apply topical decongestants.

Increase fluid intake. If nasal obstruction is still a problem

after 3 d, take oral decongestants

unless contraindicated by hypertension or coronary artery disease.

Serous otitis media or sensation of fullness in ears

Decongestants (oral)

Headache, sore throat,

malaise, myalgia, fever

Gargle with salt water, drink

plenty of fluids, suck on

menthol lozenges.

Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs Chaparral, aromatherapy

rubs, boneset

Chest congestion Drink fluids, have menthol rubs,

and humidify room air.

Expectorants

Sneezing and watery eyes Humidify room air. Two schools of thought: antihistamine

of choice, but critics say antihistamines not needed in treating colds,

especially in children

Cough Humidify room air. Antitussives, naproxen

Vicks VapoRub on the soles of feet

covered by socks at bedtime

Arcangelo_Chap24.indd 333 10/8/2011 1:52:50 PM

334 UNIT 5 | PHARMACOTHERAPY FOR RESPIRATORY DISORDERS

Inhaling warm, moist heat helps raise the temperature of the

nasal mucosa to at least 98.6°F (37°C), a temperature at which

the virus does not replicate so readily.

Applying Vicks VapoRub on the soles of the feet and then

putting on socks may help with a persistent night-time cough.

Goals of Drug Therapy

The main goals of treatment for the common cold are relief of

symptoms, reduction of the risk for complications, and prevention of spread to others (Box 24.1). Polypharmacy is often

used to treat intolerable symptoms.

Decongestants

Mechanism of Action

Decongestants are sympathomimetic agents that stimulate

alpha- and beta-adrenergic receptors, causing vasoconstriction

in the respiratory tract mucosa and thereby improving ventilation (Table 24.2). Decongestants come in topical or oral

preparations. Topical decongestants in the form of nasal sprays

slow ciliary motility and mucociliary clearance. Topical agents

have little systemic absorption. However, topical decongestants

should not be used for more than 3 days because prolonged use

can cause rhinitis medicamentosa (rebound congestion), which

is characterized by severe nasal edema, rebound congestion,

and increased discharge due to decreased receptor sensitivity.

Oral decongestants are frequently used and are sold over

the counter (OTC) alone or in combination with other drugs.

A common example of a combination preparation is an antihistamine and a decongestant. The most common oral decongestant is pseudoephedrine (Sudafed, others). Oral decongestants

have the same mode of action as topical agents but can cause

more systemic responses. Decongestants assist in clearing nasal

obstruction. Their use may be encouraged to prevent sinusitis

and eustachian tube blockage.

Contraindications

Decongestants are contraindicated in patients with narrowangle glaucoma, hypertension, and severe coronary artery

disease. Caution is recommended in patients with hyperthyroidism, diabetes, and prostatic hypertrophy (causes difficulty

with urination).

Adverse Events

Adverse events include increased blood pressure, increased

heart rate, palpitations, headache, dizziness, gastrointestinal

(GI) distress, and tremor. These reactions are especially seen at

doses above 210 mg.

Interactions

Decongestants interact with appetite suppressants, monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors (hypertensive crisis), and

beta- adrenergic agents (bradycardia and hypertension).

Decongestants are less effective when taken with drugs that

acidify the urine and more effective when taken with drugs

that alkalize the urine.

Expectorants

One of the most important nondrug considerations in treating

coughs is discovering its cause, because the prolonged use of

OTC expectorants or other cough products may mask symptoms of a serious underlying disorder. The drug should not be

used for more than a week. If the cough persists, additional

measures may be investigated.

Mechanism of Action

Expectorants, including water, increase the output of respiratory tract fluid by decreasing the adhesiveness and surface

tension of the respiratory tract and by facilitating removal of

viscous mucous. (See Table 24.2.) The effect is noted within

1 to 2 hours.

Adverse Events

Adverse events include drowsiness, headache, and GI symptoms.

Antitussives

Cough is a frequent complaint of a person with an URI. Cough

can be stimulated from congestion or can occur as a result of

postnasal drip. There are many cough suppressants available,

but studies have shown minimal benefit with the common cold.

• Avoid touching face with hands.

• Wash hands frequently.

• Avoid people with colds or URIs.

• Avoid crowded areas during peak URI/flu season.

• Stop smoking.

• Avoid excessive intake of alcohol.

• Avoid second-hand smoke.

• Avoid excessive dry heat.

• Use disposable tissues and dispose of them properly.

• Obtain influenza vaccine, if recommended.

• Eat a nutritious diet.

• Get adequate rest and sleep.

• Avoid or reduce stress.

• Exercise regularly.

• Increase humidity in the house, especially during

winter months.

• Maintain good oral hygiene.

• Avoid certain environmental irritants and allergens

(dust, chemicals, smoke, and animal dander) when

possible.

• Use central ventilation fans/air conditioning with

microstatic air filters.

BOX 24.1

Preventing Upper

Respiratory Infections

Arcangelo_Chap24.indd 334 10/8/2011 1:52:50 PM

CHAPTER 24 | UPPER RESPIRATORY INFECTIONS 335

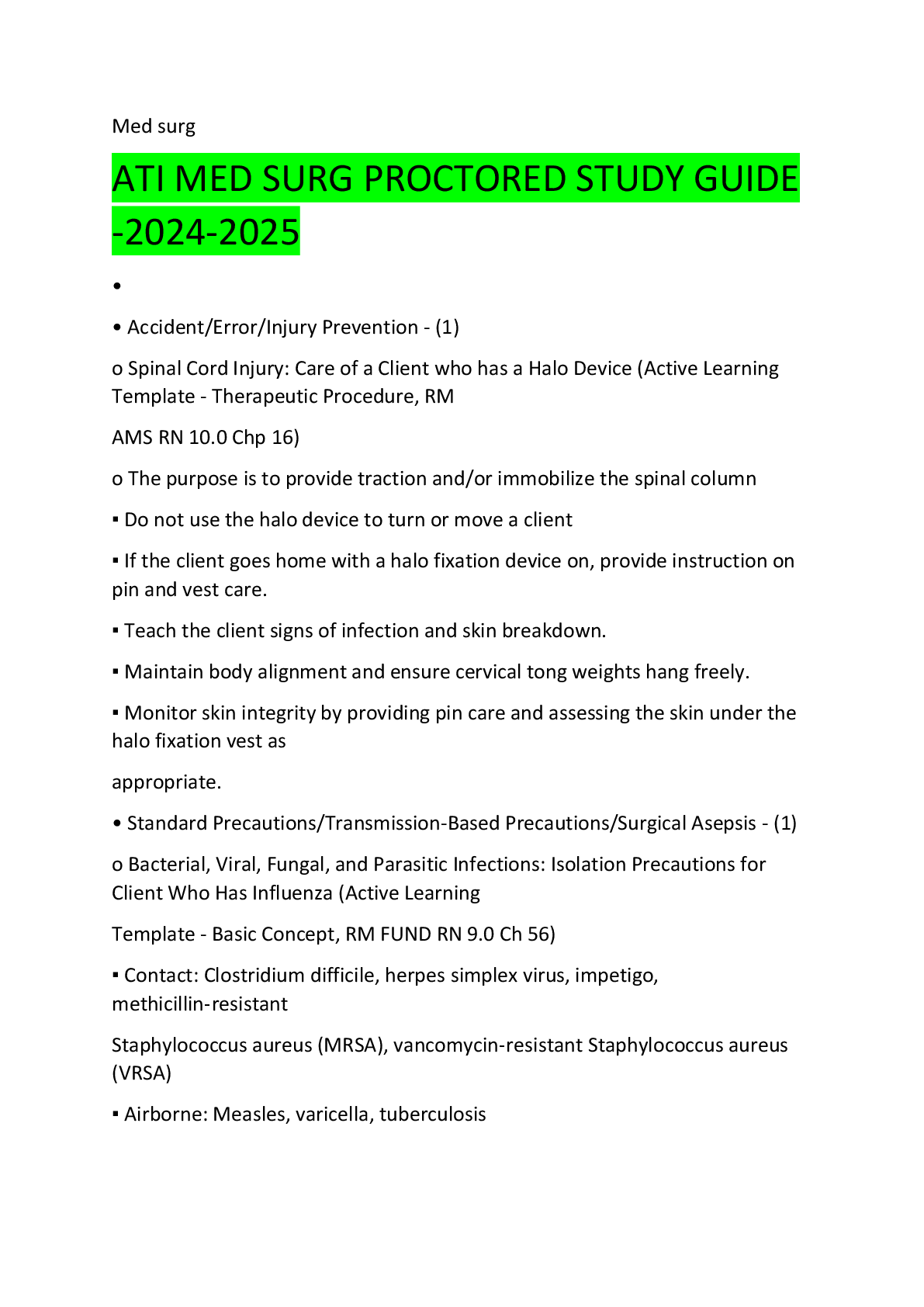

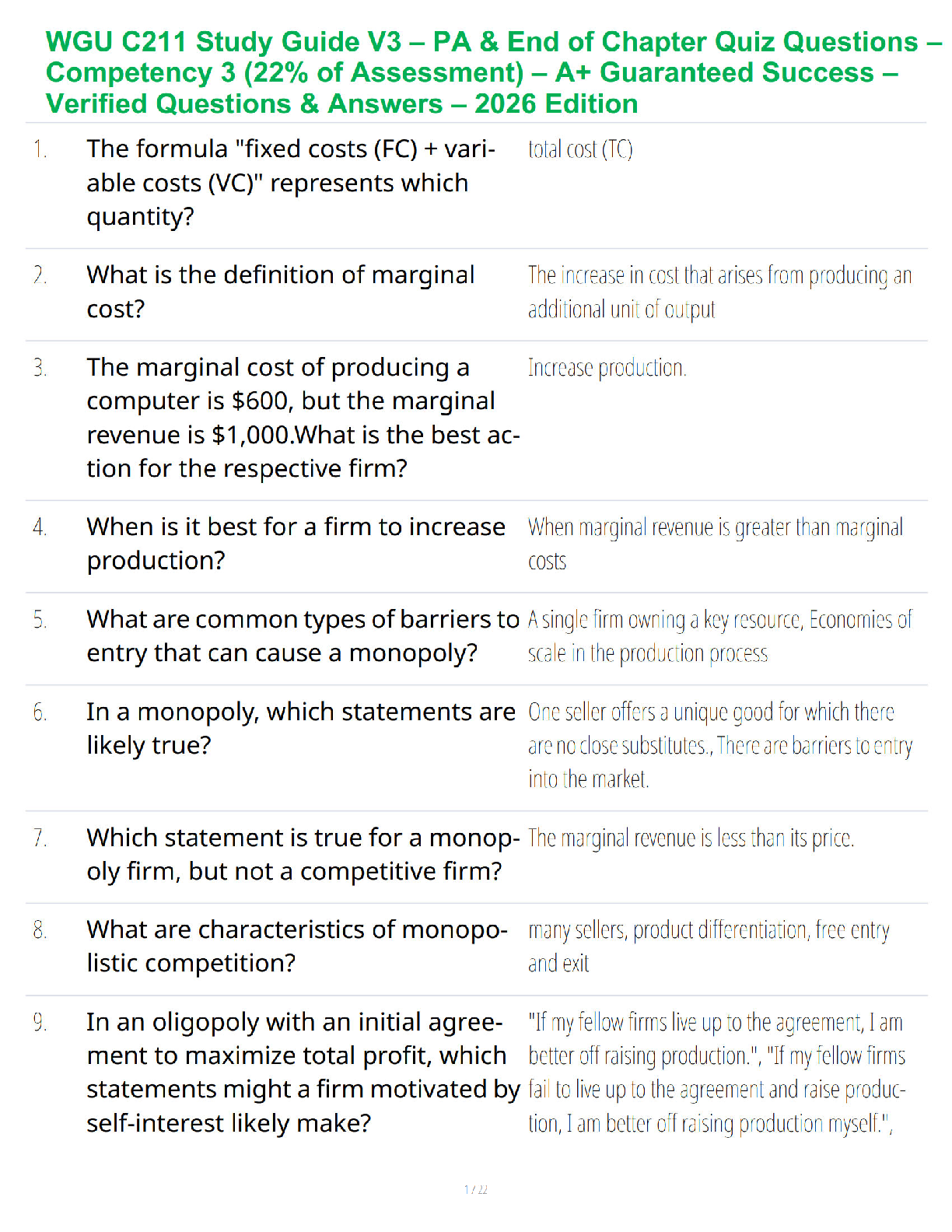

TABLE 24.2 Overview of Agents for Upper Respiratory Infections

Generic (Trade)

Name and Dosage Selected Adverse Events Contraindications Special Considerations

Decongestants

oxymetazoline hydrochloride

(Afrin) ≥6 y: 2–3 sprays bid 2–6 y

(use children’s spray): 2–3 sprays

bid

Palpitations, headaches These drugs may cause

rebound congestion.

Use only 2 to 3 days, then

switch to oral decongestants.

phenylephrine hydrochloride

(Neo-Synephrine)

Adults: 1 spray q3–4h as needed

Palpitations, headaches Not recommended for

children

These drugs may cause

rebound congestion.

Use only 2 to 3 days, then

switch to oral decongestants.

pseudoephedrine (Sudafed, Benylin

decongestant)

Adults: short acting: 60 mg q4–6h;

long acting: 120 mg q12h

Children 7–12 y: short acting: 30 mg

q4–6h

Children 3–6 y: 15 mg q4–6h

Palpitations, headaches,

increased blood pressure,

dizziness, GI upset, tremor

Hypertension, coronary

artery disease

Give at least 2 h before bedtime. Do not crush, break, or

chew tablets.

Expectorants

guaifenesin (Antitussin, Mucinex,

Robitussin, Uni-Tussin)

Adults: short acting: 200–400 mg

q4h

long acting: 600–1,200 mg q12h

Children 7–12 y: short acting:

100–200 mg q4h

long acting: 600 mg q12h

Children 2–6 y: 50–100 mg q4h

GI upset, drowsiness,

headache, rash, dizziness

Breast-feeding mothers,

pregnancy category C

Not given for prolonged time if

cough persists or accompanied by high fever

Humibid sprinkles may be

swallowed whole or opened

and sprinkled on soft food.

Antitussives

dextromethorphan

(Benylin—15 mg/5 mL) 10 mL q6–8h

(Delsym—30 mg/5 mL)

Adults: 10 mL q12h

Children 2–5 y: 2.5 mL q12h

6–12 y: 5 mL q12h

benzonatate (Tessalon)

100–200 mg tid

Not for ≤ 10 years old

Drowsiness, palpitations,

excitability in children

Drowsiness, headache, GI

upset, confusion

Hypertension, diabetes,

asthma

Pregnancy category C

None

Narcotic Antitussives

codeine phosphate 10 mg, guaifenesin

300 mg tablets

and liquid (Brontex)

Adults: 20 mL q4h

Children 6–12 y: 10 mL q4h

Lightheadedness, dizziness,

sedation, sweating,

nausea, vomiting

Known addiction, cautious

use in asthmatics, COPD,

cardiac disease, seizure

disorders, renal/hepatic

impairment, BPH, head

injuries, hypothyroidism,

and pregnancy

Increased CNS depression if

used with alcohol or other

narcotics

Usually used with antihistamines, expectorants, decongestants, or analgesics

Controlled substance (Drug

Enforcement Agency number

required for prescription)

Phenergan with codeine (codeine 10 mg

and promethazine 6.25 mg/5 mL)

Adults: 5 mL

Children: 2–5 y: 1.25–2.5 mL q4h

6–12 y: 2.5–5 mL q4h

Same as above Same as above Same as above

(continued )

Arcangelo_Chap24.indd 335 10/8/2011 1:52:50 PM

336 UNIT 5 | PHARMACOTHERAPY FOR RESPIRATORY DISORDERS

TABLE 24.2 Overview of Agents for Upper Respiratory Infections (Continued )

Generic (Trade)

Name and Dosage Selected Adverse Events Contraindications Special Considerations

codeine 10 mg, guaifenesin

100 mg/5 mL (Robitussin AC) or

codeine 10 mg, pseudoephedrine

30 mg, and guaifenesin

100 mg/5 mL (Tussar SF)

Adults: 10 mL q4h to maximum of

40 mL/d

Same as above Children: not recommended Same as above

hydrocodone (in combination with other

agents) 5 mg up to 4 qid

Same as above Known addiction; cautious

use in asthmatics, COPD,

cardiac disease, seizure

disorders, renal/hepatic

impairment, BPH, head

injuries, hypothyroidism,

and pregnancy

Same as above

hydrocodone 2.5 mg, guaifenesin

100 mg, pseudoephedrine 30 mg/

5 mL (Duratuss HD)

Same as above Same as above Same as above

Adults: 10 mL q4–6h

Children 6–12 y: 5 mL q2–6h

Maximum of 4 doses/d

hydrocodone 5 mg and homatropine

1.5 mg (Hycodan tablets and syrup)

Same as above Same as above Same as above

Adults: 1 tablet or 5 mL q4–6h

Children: 6–12 y: ½ tablet or 2.5 mL

q4–6h

hydrocodone 5 mg and guaifenesin

100 mg/5 mL (Hycotuss)

Adults: 5 mL after meals and hs

Children: 6–12 y: 2.5–5 mL after

meals and hs

Same as above Same as above Same as above

hydrocodone 10 mg and chlorpheniramine maleate 8 mg/5 mL

(Tussionex)

Adults: 5 mL q12h

Children: 6–12 y: 2.5 mL q12h

Same as above Same as above Same as above

hydrocodone 5 mg guaifenesin 100 mg

per 5 mL (Vicodin Tuss)

Adults: 5 mL at meals and hs

Children 6–12 y: 2.5 mL at meals

and hs

Same as above Same as above Same as above

Combination Products—Non-Narcotic

dextromethorphan hydrobromide

10 mg, brompheniramine maleate

2 mg, pseudoephedrine 30 mg/5 mL

(Bromfed-D, Dimetane-DX)

Adults: 10 mL q4h

Children: 2–5 y: 2.5 mL q4h 6–12 y:

5 mL q4h

Drowsiness, sedation,

nausea, dizziness, palpitations, increased blood

pressure, excitation in

children, constipation

Asthma, lower respiratory

disorders, neonates,

severe hypertension,

severe cardiovascular

disease, within 14 d of

monoamine oxidase inhibitors, nursing mothers; use

cautiously in patients with

history of urinary obstruction, mild hypertension,

and hyperthyroidism

These drugs are combination

antitussives, antihistamines,

and sympathomimetics.

Used for cough and congestion

Pregnancy category C

Not recommended for children

<2 y

These drugs are sold over the

counter.

[Show More]

-2.png)

-3.png)