Transactions and Concurrency

Susan B. Davidson

University of Pennsylvania

CIS450/550 – Database & Information Systems

September 23-28, 2015

Some slide content derived from Ramakrishnan & Gehrke2

From Queries to Upd

...

Transactions and Concurrency

Susan B. Davidson

University of Pennsylvania

CIS450/550 – Database & Information Systems

September 23-28, 2015

Some slide content derived from Ramakrishnan & Gehrke2

From Queries to Updates

§ We’ve spent a lot of time talking about querying data

§ Yet updates are a really major part of many DBMS

applications

§ Standard notion for updates is a transaction:

§ Sequence of read and write operations on data items that

logically functions as one unit of work

§ If it succeeds, the effects of all write operations persist

(commit); if it fails, no effects persist (abort)

§ These guarantees are made despite concurrent activity in

the system, and despite failures that may occurOutline

§ Transactions and ACID properties: the dangers in

concurrent executions (Ch. 16:1-3)

§ Two-Phase Locking (Ch. 16:4)

§ Transactions and SQL: isolation levels (Ch. 16.6)

§ How the database implements isolation levels (Ch.

16:4-5)

3ACID Properties

§ Atomicity: either all of the actions of a transaction are

executed, or none are.

§ Consistency: each transaction executed in isolation keeps

the database in a consistent state (this is the responsibility

of the user and constraints on the db)

§ Isolation: can understand what’s going on by considering

each transaction independently. Transactions are isolated

from the effects of other, concurrently executing,

transactions.

§ Durability: updates stay in the DBMS!!!

45

How Things Can Go Wrong

§ Suppose we have a table of bank accounts which contains the

balance of the account

§ An ATM deposit of $50 to account # 1234 would be written

as:

§ This reads and writes the account’s balance

update Accounts

set balance = balance + $50

where account#= ‘1234’;

What if two account holders make deposits simultaneously

from two ATMs?6

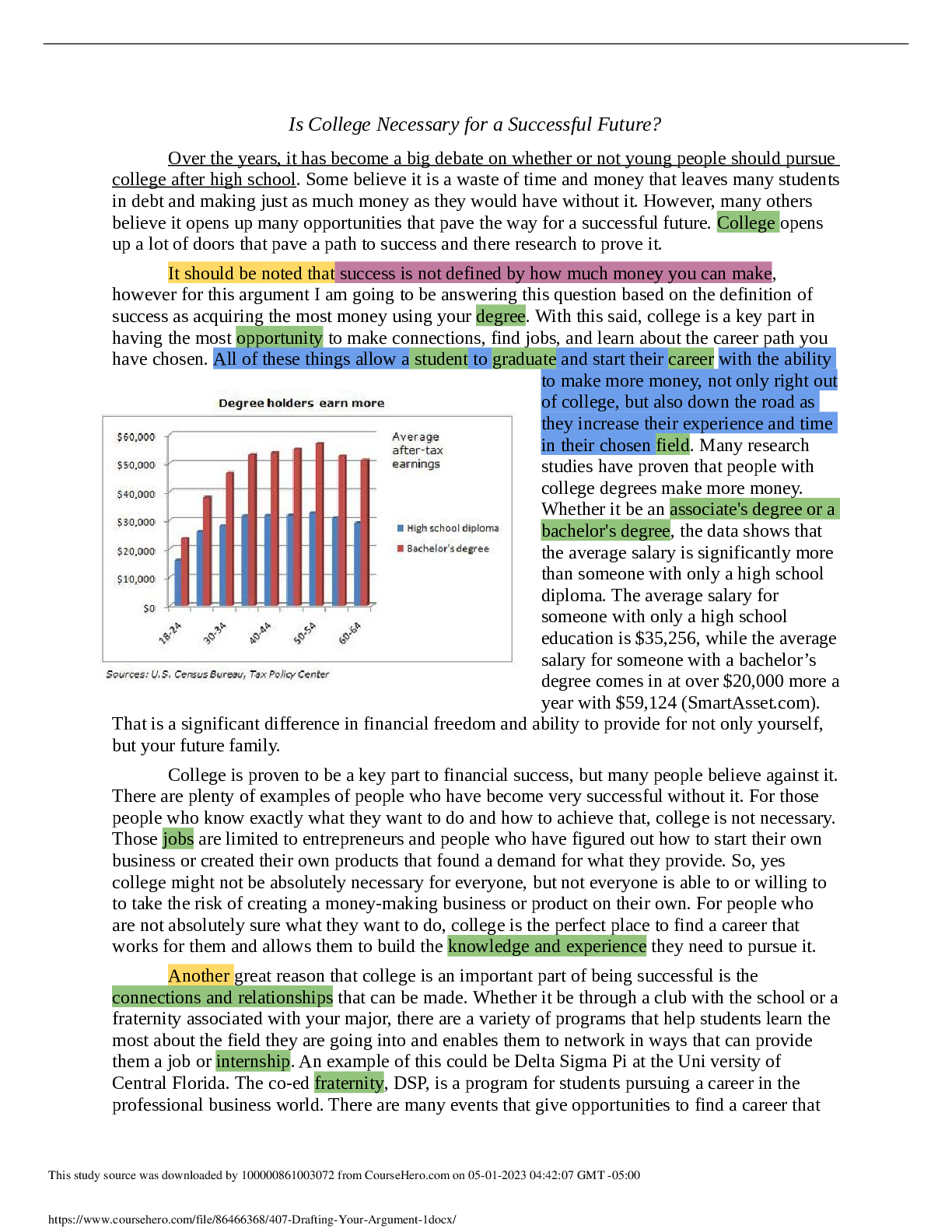

Concurrent Deposits

This SQL update code is represented as a sequence of read

and write operations on “data items” (which for now should

be thought of as individual accounts):

where X is the data item representing the account with

account# 1234.

Deposit 1 Deposit 2

read(X.bal) read(X.bal)

{X.bal := X.bal + $50} {X.bal:= X.bal + $10}

write(X.bal) write(X.bal)7

Isolation

Only one “action” (e.g. a read or a write) can actually happen

at a time, but we can allow concurrent executions of

transactions in which their actions are interleaved. Some

concurrent executions are “bad”:

Deposit 1 Deposit 2

read(X.bal)

read(X.bal)

{X.bal := X.bal + $50}

{X.bal:= X.bal + $10}

write(X.bal)

write(X.bal)

time

BAD!

Why allow concurrent executions?8

A “Good” Execution

§ The previous execution would have been fine if the accounts

were different (i.e. one were X and one were Y), i.e.,

transactions were independent

§ The following execution is a serial execution, and executes

one transaction after the other:

Deposit 1 Deposit 2

read(X.bal)

{X.bal := X.bal + $50}

write(X.bal)

read(X.bal)

{X.bal:= X.bal + $10}

write(X.bal)

time

GOOD!9

Good Executions

An execution is “good” if it is serial (transactions are executed

atomically and consecutively) or serializable (i.e. equivalent to

some serial execution)

Equivalent to executing Deposit 1 then 3, or vice versa.

Deposit 1 Deposit 3

read(X.bal)

read(Y.bal)

{X.bal := X.bal + $50}

{Y.bal:= Y.bal + $10}

write(X.bal)

write(Y.bal)

Why are serializable executions good?10

Testing for Serializability

§ Given a schedule S, we can construct a directed

graph G=(V,E) called a precedence graph

§ V : all transactions in S

§ E : T

i → Tj whenever an action of Ti precedes and

conflicts with an action of T

j in S

i.e. they both operate on the same data item and at least one of

them writes (RW, WR, WW conflicts)

§ A schedule S is conflict serializable if and only if its

precedence graph contains no cycles

Note that testing for a cycle in a digraph can be done in time O(|

V|2)11

An Example

T1 T2 T3

R(X,Y,Z)

R(X)

W(X)

R(Y)

W(Y)

R(Y)

R(X)

W(Z)

T1 T2 T3

Cyclic: Not serializable.12

Atomicity

Problems can also occur if a crash occurs in the middle of

executing a transaction:

Need to guarantee that the write to X does not persist

(ABORT)

§ Default assumption if a transaction doesn’t commit

Transfer

read(X.bal)

read(Y.bal)

{X.bal= X.bal-$100}

write(X.bal)

Y.bal= Y.bal+$100

write(Y.bal)

CRASHOutline

§ Transactions and ACID properties: the dangers in

concurrent executions (Ch. 16:1-3)

§ Two-Phase Locking (Ch. 16:4)

§ Transactions and SQL: isolation levels (Ch. 16.6)

§ How the database implements isolation levels (Ch.

16:4-5)

1314

Controlling conflicts through

Locking

§ Recall: two actions by different transactions conflict if

§ they operate on the same data item

§ at least one is a write

§ To avoid conflict

§ Each data item is either locked (in some mode, e.g. shared

or exclusive) or is available (no lock)

§ Before a read, a shared lock must be acquired

§ Before a write, an exclusive lock must be acquired

§ An action on a data item can only be executed if the

transaction holds an appropriate lock15

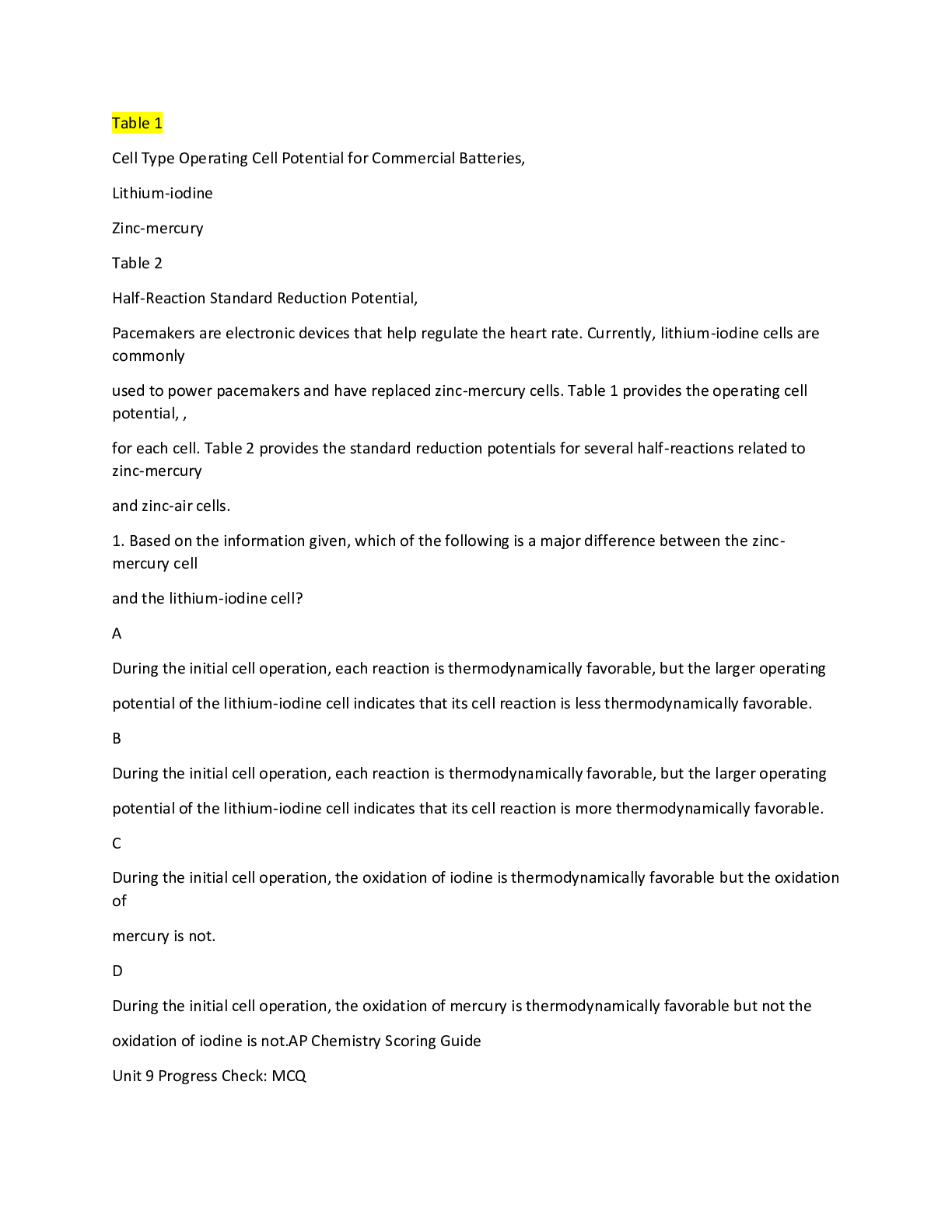

Lock Compatibility Matrix

Locks on a data item are granted based on a lock

compatibility matrix:

When a transaction requests a lock, it must wait

(block) until the lock is granted or may be

aborted

Mode of Data Item

None Shared Exclusive

Shared Y Y N

Request mode{ Exclusive Y N N16

Locks Prevent “Bad” Execution

If the system used locking, the first “bad” execution could

have been avoided:

Deposit 1 Deposit 2

xlock(X)

read(X.bal)

{xlock(X) is not granted}

{X.bal := X.bal + $50}

write(X.bal)

release(X)

xlock(X)

read(X.bal)

{X.bal:= X.bal + $10}

write(X.bal)

release(X)17

But locks are not enough…

Deposit 1 Deposit 2

slock(X)

read(X.bal)

slock(X)

read(X.bal)

release(X)

release(X)

{X.bal:= X.bal + $10}

{X.bal := X.bal + $50}

xlock(X)

write(X.bal)

release(X)

xlock(X)

write(X.bal)

release(X)18

Well-Formed, Two-Phased

Transactions

§ A transaction is well-formed if it acquires at least

a shared lock on Q before reading Q or an

exclusive lock on Q before writing Q and

doesn’t release the lock until the action is

performed

§ Locks are released by the end of the transaction

§ Holding locks until the end is called strict locking

§ A transaction is two-phased if it never acquires a

lock after unlocking one

§ i.e., there are two phases: a growing phase in which the

transaction acquires locks, and a shrinking phase in

which locks are released19

Two-Phased Locking Theorem

§ If all transactions are well-formed and two-phase,

then any schedule in which conflicting locks are

never granted ensures serializability

§ i.e., there is a very simple scheduler!

§ However, if some transaction is not well-formed or

two-phase, then there is some schedule in which

conflicting locks are never granted but which fails

to be serializable

§ i.e., one bad apple spoils the bunchOutline

§ Transactions and ACID properties: the dangers in

concurrent executions (Ch. 16:1-3)

§ Two-Phase Locking (Ch. 16:4)

§ Transactions and SQL: isolation levels (Ch.

16.6)

§ How the database implements isolation levels (Ch.

16:4-5)

2021

Transactions in SQL

§ A transaction begins when any SQL statement that queries

the db begins.

§ To end a transaction, the user issues a COMMIT or

ROLLBACK statement.

Transfer

UPDATE Accounts

SET balance = balance - $100

WHERE account#= ‘1234’;

UPDATE Accounts

SET balance = balance + $100

WHERE account#= ‘5678’;

COMMIT;22

Read-Only Transactions

§ When a transaction only reads information, we

have more freedom to let the transaction execute

concurrently with other transactions.

§ We signal this to the system by stating:

SET TRANSACTION READ ONLY;

SELECT * FROM Accounts

WHERE account#=‘1234’;

...23

Read-Write Transactions

§ If we state “read-only”, then the transaction cannot

perform any updates.

§ Instead, we must specify that the transaction may

update (the default):

SET TRANSACTION READ ONLY;

UPDATE Accounts

SET balance = balance - $100

WHERE account#= ‘1234’; ...

SET TRANSACTION READ WRITE;

update Accounts

set balance = balance - $100

where account#= ‘1234’; ...

ILLEGAL!24

WR Conflicts: Dirty Reads

§ Dirty data is data written by an uncommitted

transaction; a dirty read is a read of dirty data

§ Sometimes we can tolerate dirty reads; other times

we cannot.25

“Bad” Dirty Read

EXEC SQL select balance into :bal

from Accounts

where account#=‘1234’;

if (bal > 100) {

EXEC SQL update Accounts

set balance = balance - $100

where account#= ‘1234’;

EXEC SQL update Accounts

set balance = balance + $100

where account#= ‘5678’;

}

EXEC SQL COMMIT;

If the initial read (italics) were dirty, the balance

could become negative!26

Acceptable Dirty Read

If we are just checking availability of an airline

seat, a dirty read might be fine! (Why is that?)

Reservation transaction:

EXEC SQL select occupied into :occ

from Flights

where Num= ‘123’ and date=11-03-99

and seat=‘23f’;

if (!occ) {EXEC SQL

update Flights

set occupied=true

where Num= ‘123’ and date=11-03-99

and seat=‘23f’;}

else {notify user that seat is unavailable}27

Other Undesirable Phenomena

§ Unrepeatable read (RW conflict): a transaction

reads the same data item twice and gets different

values

§ The airline seat reservation is an example of where an

unrepeatable read could occur.

§ Overwriting uncommitted data (WW conflict): one

transaction overwrites the value of data that is in the

process of being written by another transaction

§ The “bad” concurrent deposit was an example of this.28

Phantom Problem Example

§ T

1: “find the students with best grades who Take either

cis550-f03 or cis570-f02”

§ T

2: “insert new entries for student #1234 in the Takes

relation, with grade A for cis570-f02 and cis550-f03”

§ Suppose that T1 consults all students in the Takes relation

and finds the best grades for cis550-f03

§ Then T

2 executes, inserting the new student at the end of

the relation, perhaps on a page not seen by T1

§ T

1 then completes, finding the students with best grades

for cis570-f02 and now seeing student #123429

Isolation

§ The problems we’ve seen are all related to isolation

§ General rules of thumb w.r.t. isolation:

§ Fully serializable isolation is more expensive than “no

isolation”

We can’t do as many things concurrently (or we have to undo

them frequently)

§ For performance, we generally want to specify the most

relaxed isolation level that’s acceptable

Note that we’re “slightly” violating a correctness constraint to

get performance!30

Specifying Acceptable Isolation Levels

§ The default isolation level is SERIALIZABLE (as for

the transfer example).

§ To signal to the system that a dirty read is

acceptable,

§ In addition, there are

SET TRANSACTION READ WRITE

ISOLATION LEVEL READ UNCOMMITTED;

SET TRANSACTION

ISOLATION LEVEL READ COMMITTED;

SET TRANSACTION

ISOLATION LEVEL REPEATABLE READ;31

READ COMMITTED

§ Forbids the reading of dirty (uncommitted) data, but

allows a transaction T to issue the same query several

times and get different answers

§ No value written by T can be modified until T completes

§ For example, the Reservation example could also be

READ COMMITTED; the transaction could

repeatably poll to see if the seat was available,

hoping for a cancellation32

REPEATABLE READ

§ What it is NOT: a guarantee that the same query

will get the same answer!

§ However, if a tuple is retrieved once it will be

retrieved again if the query is repeated

§ For example, suppose Reservation were modified to

retrieve all available seats

§ If a tuple were retrieved once, it would be retrieved again

(but additional seats may also become available)33

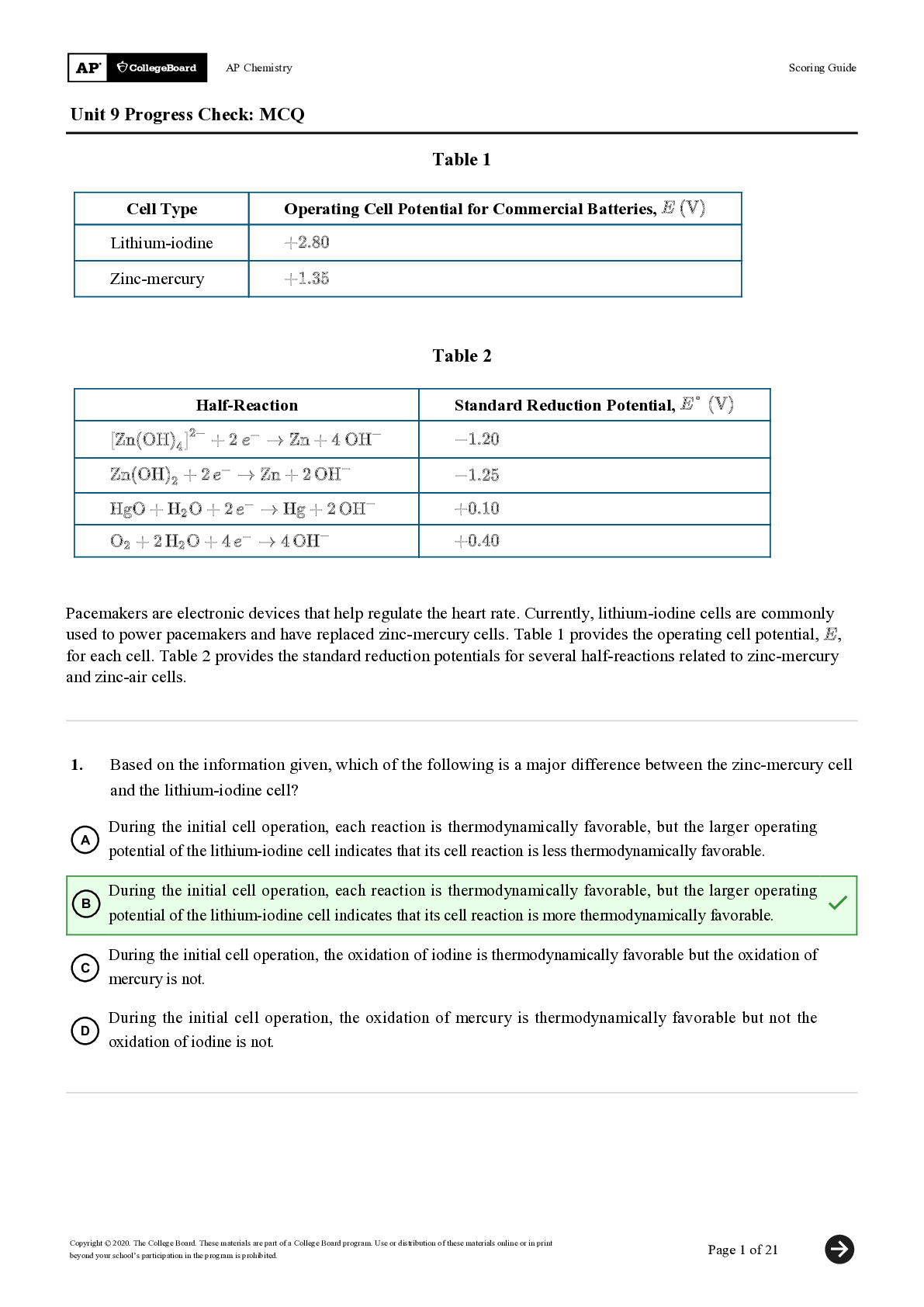

Summary of Isolation Levels

Level Dirty Read Unrepeatable Read Phantoms

READ UN- Maybe Maybe Maybe

COMMITTED

READ No Maybe Maybe

COMMITTED

REPEATABLE No No Maybe

READ

SERIALIZABLE No No NoOutline

§ Transactions and ACID properties: the dangers in

concurrent executions (Ch. 16:1-3)

§ Two-Phase Locking (Ch. 16:4)

§ Transactions and SQL: isolation levels (Ch. 16.6)

§ How the database implements isolation levels

(Ch. 16:4-5)

3435

Lock Types and Read/Write Modes

When we specify “read-only”, the system only uses

shared-mode locks

§ Any transaction that attempts to update will be illegal

When we specify “read-write”, the system may also

acquire locks in exclusive mode

§ Obviously, we can still query in this mode36

Isolation Levels and Locking

READ UNCOMMITTED allows queries in the

transaction to read data without acquiring any lock

Access mode READ ONLY, no updates are allowed

READ COMMITTED requires a read-lock to be

obtained for all tuples touched by queries, but it

releases the locks immediately after the read

Exclusive locks must be obtained for updates and held to

end of transaction37

Isolation levels and locking, cont.

REPEATABLE READ places shared locks on tuples

retrieved by queries, holds them until the end of the

transaction

Exclusive locks must be obtained for updates and held to

end of transaction

SERIALIZABLE places shared locks on tuples retrieved

by queries as well as the index, holds them until the end

of the transaction

Exclusive locks must be obtained for updates and held to

end of transaction

Holding locks to the end of a transaction is called

“strict” locking38

Summary

§ Transactions are all-or-nothing units of work

guaranteed despite concurrency or failures in the

system.

§ Theoretically, the “correct” execution of

transactions is serializable (i.e. equivalent to some

serial execution).

§ Practically, this may adversely affect throughput

⇒ isolation levels.

§ With isolation levels, users can specify the level of

“incorrectness” they are willing to tolerate.

[Show More]