Unit 1 Tutorials: Great Philosophers

INSIDE UNIT 1

Introduction to Philosophy and the Pre-Socratics

What is Philosophy?

Why Study Philosophy?

Cosmology and the First Philosophers

The Atomistic Worldview

Parmenides

...

Unit 1 Tutorials: Great Philosophers

INSIDE UNIT 1

Introduction to Philosophy and the Pre-Socratics

What is Philosophy?

Why Study Philosophy?

Cosmology and the First Philosophers

The Atomistic Worldview

Parmenides and the Doctrine of Permanence

Heraclitus and the Doctrine of Impermanence

Socrates and Dialectic

Socrates: The Father of Western Philosophy

The Socratic Approach

Introducing Arguments

Evaluation and Analysis of Arguments

Evaluating an Argument in Action

The Apology: A Defense of Philosophy

The Apology- Socrates' Arguments

The Crito: The Duties of the Social Contract

The Phaedo: The Death of Socrates

Plato and Aristotle

Plato: An academic approach to concepts

Plato Forms: The Objects of Knowledge

Plato Forms: The Foundations of Being

Applying Plato's Metaphysics

The Footnotes to Plato

Aristotle: The Dissection of Reality

Aristotle on What There Is

Plato vs. Aristotle: The Mathematician or the Biologist

Philosophy as a Way of Life

Aristotelianism: The Naturalistic Worldview

Aristotle's Highest Good

Applying Aristotle's Ethics

Stoicism: The Ethics of Dispassion

Philosophical Analysis as a Way of Life

What is Philosophy?

by Sophia Tutorial

© 2018 SOPHIA Learning, LLC. SOPHIA is a registered trademark of SOPHIA Learning, LLC. Page 1Philosophy is a field of study that many people (including students) don't know much about. This course enables you to increase

your knowledge of philosophy by examining its origins in ancient Greece, as well as some of the areas that are studied by

philosophers today, including logic, epistemology, ethics, and metaphysics.

This section responds to the question, "What is Philosophy?" in three parts:

1. The Beginning of Western Philosophy

2. The Big Picture and a Contemporary Definition

3. Some Major Branches of Philosophy

1. The Beginning of Western Philosophy

Western philosophy is traditionally thought to have started when a mathematician named Thales of Miletus successfully predicted an

eclipse in 585 BCE. Although this may seem to have been an accomplishment in the field of astronomy, not philosophy, astronomy, like

many other sciences, was once considered to be a branch of philosophy.

Imagine for a moment that you lived in Greece 2600 years ago, but Thales had not made his famous prediction about the eclipse. What

would people have thought caused the eclipse? Would they have concluded that the gods were angry, or bringing the world to an end?

Whatever conclusions might have been reached about the meaning of the event, it's likely that it would have been connected to the

gods. By making his prediction based on analysis of his observations, Thales demonstrated that humans were capable of interpreting

reality on their own, without divine assistance.

Thales demonstrated that the world was fundamentally understandable and predictable. Human beings do not need to appeal to the

gods to learn about the world, or to use what they learn. By applying reason to observations, people can solve many of life's puzzles.

The desire to know and learn is the foundation of philosophy.

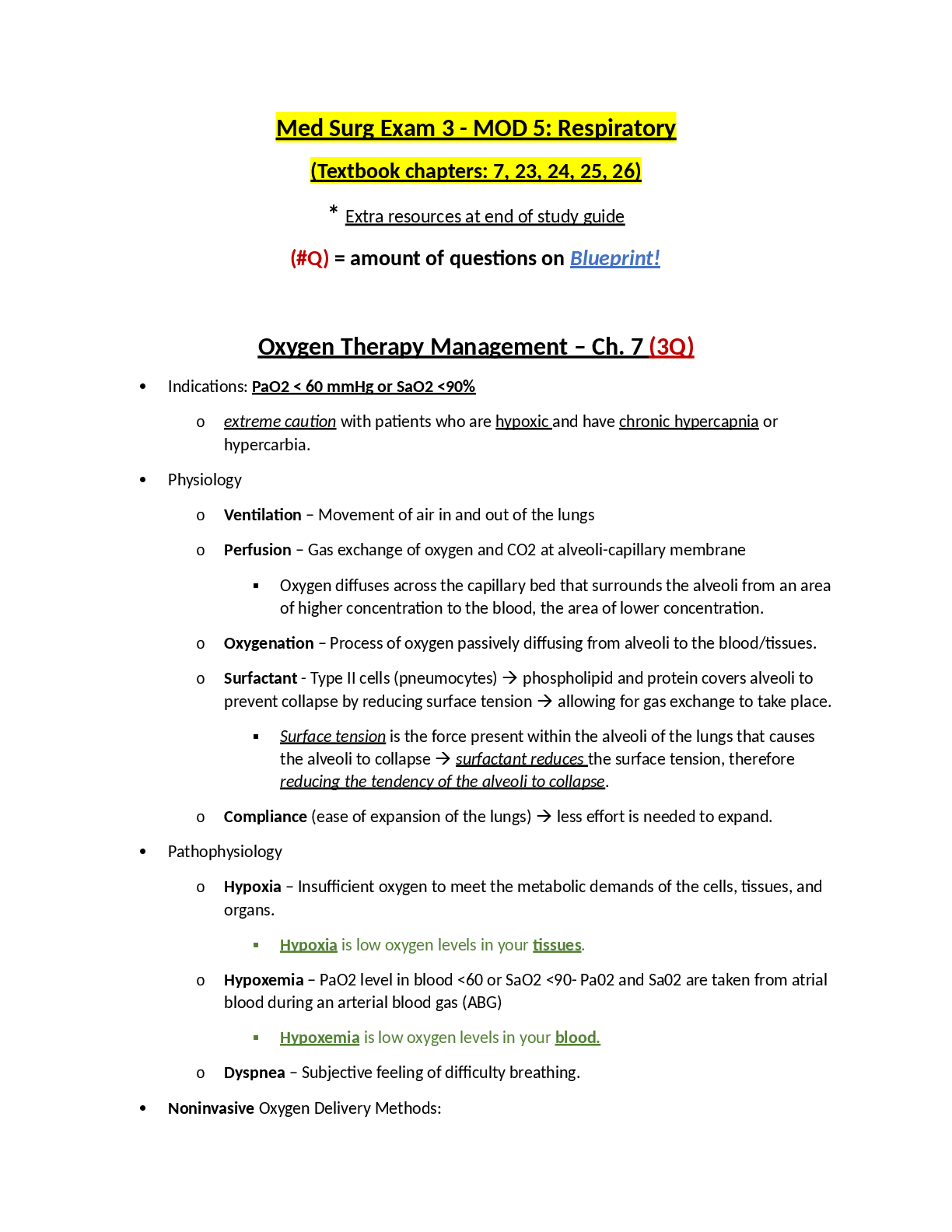

Illustration of Thales.

2. The Big Picture and a Contemporary Definition

To better understand what philosophy involves, consider the etymology of the word, “philosophy.” It comes from two Greek words,

philos and sophia. Philos means "love." It is the basis of a number of common words, including “philanthropy” and “Philadelphia.” Sophia,

which is also part of “sophisticated” and “sophomore,” means “wisdom” (and before you sophomores start feeling too proud,

sophomore means “wise fool”). Philosophy, at a fundamental level, is the love of wisdom.

Wisdom is not the same as knowledge. One can have all of the knowledge in the world but still lack wisdom. Rather than referring to

information retained in memory (i.e, knowledge), wisdom refers to the ability to apply reason to knowledge, in order to make use of it in

beneficial ways. Wisdom focuses on how we use what we learn, rather than on what we learn.

© 2018 SOPHIA Learning, LLC. SOPHIA is a registered trademark of SOPHIA Learning, LLC. Page 2The highest degree one can earn in biology is a PhD — a doctorate in philosophy. A PhD in biology not only means that you know facts

and concepts in the field (i.e., knowledge), but that you can use that knowledge to make new contributions — in biology or a related

field. You can evaluate the body of biological knowledge and determine how parts of it can be used in new ways. As a result of

philosophy's focus on wisdom, science and philosophy share a similar methodology.

Defining philosophy as “love of wisdom” helps us to begin to understand it, but it lacks precision. Here is the definition of philosophy

that we will use in this course:

Philosophy

The pursuit of truths that cannot be wholly determined empirically.

Philosophy seeks to find truth in areas where science cannot.

Consider this philosophical question: “Is there a creator god of a certain description?" We cannot answer this question

by looking for a god through a telescope. In this instance, science cannot help us to find the truth. There are two possible answers to

this question: "there is" or "there isn’t."

In seeking to arrive at the truth, philosophy is not mere opinion. If two people disagree, this doesn’t mean that it is not possible to find

an answer, and that they must agree to disagree. With respect to the example above, If two people disagree as to what is true, one of

them is simply wrong. Philosophy helps us to determine which one.

Since we cannot use a telescope, a microscope, etc. to discover who is right and who is wrong, we must make inferences: We take the

evidence we have, and ask whether it supports one position or the other. We use logic to decide which position is better-supported

and, therefore, more reasonable. It is for this reason that logic is the backbone of philosophy.

3. Some Major Branches of Philosophy

Philosophy encompasses a number of branches/sub-disciplines. The three most significant branches involving the philosophers we'll

study in this course are ethics, epistemology, and metaphysics.

Ethics

The branch of philosophy that analyzes and defends concepts of value, and thereby determines right and wrong.

Questions of right and wrong fit within the definition of philosophy provided above. Consider this action: punching a small child. The

sciences can tell us a lot about this action. Medicine can predict the damage it would cause. Political science can determine its legal

consequences. Psychology can provide insight into the mind of the perpetrator. But no scientific analysis can tell us that this action is

wrong.

Of course, it is wrong, and anyone who claims that "wrong" is merely an opinion, and that this action is not something that can be true or

false, should be ignored. Science can tell us that this action would cause pain, but it is a philosophical truth that causing pain

unnecessarily is wrong.

Although questions of right and wrong are the prerogative of philosophy, science has a role. Later in the course, we will consider

philosophical approaches to ethics, including the philosophy of Socrates, who was not only deeply interested in determining how to live

a morally upright life, but was willing to die to uphold his beliefs.

Philosophy provides a benefit to science through epistemology.

Epistemology

The branch of philosophy that analyzes and defends concepts of knowledge and the methodologies by which it is attained.

Philosophy is sometimes called the "mother of the sciences" because it determines what constitutes knowledge. For example, it helps

biologists determine what is biological knowledge (versus mere opinion), and what methods can generate knowledge. Philosophers of

science were the driving force behind the development and refinement of the scientific method. Socrates distinguished knowledge

from opinion, while Plato gave the first clear account of knowledge. Aristotle, the father of physics, biology, and astronomy, used

philosophy to develop and enhance these disciplines.

The largest and, perhaps, the most fundamental branch of philosophy is metaphysics.

Metaphysics

The branch of philosophy that seeks to uncover and describe the ultimate nature of reality.

The prefix “meta” means “beyond.” Metaphysics works on fundamental issues that are beyond science — principles in which science

may be grounded. For instance, although science identifies and describes the laws of physics, what is a law? What is its status? What kind

of a thing is it? These are metaphysical questions. Metaphysics also considers questions including, is there a god? Are we free to make

© 2018 SOPHIA Learning, LLC. SOPHIA is a registered trademark of SOPHIA Learning, LLC. Page 3decisions, or are all of our choices predetermined? What is the ultimate nature of time? What is causation? All of the philosophers

included in this course have something to say about these topics. Additionally, we'll learn how metaphysics informs other philosophical

disciplines, such as ethics.

These three branches of philosophy will be a major focus of this course. Other branches of philosophy (e.g.,natural philosophy and

cosmology), have been largely relegated to the sciences.

Natural Philosophy

The branch of philosophy that examines nature and the universe

Cosmology

The branch of philosophy that studies the universe in its totality

The subjects studied in what was called "natural philosophy" have moved from philosophy to physics, astronomy, and other sciences.

Cosmology is now a branch of astrophysics (cosmogony is a branch of cosmology that focuses on the origin of the universe).

Since philosophy is the pursuit of wisdom, it supports all pursuits of knowledge. To discover wisdom, philosophy uses logic,

reason, and critical thinking, and studies topics including ethics, epistemology, and metaphysics. In this course, we’ll learn about

these branches of philosophy, practice logic, and examine philosophical approaches to questions including “what is knowledge?”

“what is real?” and “what is a good life and how should I live?”

Source: Image of Thales, PD,

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thales_of_Miletus#/media/File:Illustrerad_Verldshistoria_band_I_Ill_107.jpg

TERMS TO KNOW

Cosmology

The branch of philosophy that treats the universe in its totality

Epistemology

The branch of philosophy that analyzes and defends concepts of knowledge and the methodologies that attain it

Ethics

The branch of philosophy that analyzes and defends concepts of value and thereby seeks to determine right and wrong

Metaphysics

The branch of philosophy that seeks to uncover and describe the ultimate nature of reality

Natural Philosophy

The branch of philosophy that treats nature and the universe

Philosophy

The pursuit of truths that cannot be wholly determined empirically

© 2018 SOPHIA Learning, LLC. SOPHIA is a registered trademark of SOPHIA Learning, LLC. Page 4Why Study Philosophy?

by Sophia Tutorial

Philosophy is sometimes stereotyped as an "ivory tower" discipline that does not apply to the "real" world. In this lecture, we will

cover four areas in which the benefits of philosophy are easy to see: higher education, the sciences, society, and the people who

study philosophy.

This section answers the question, "Why Study Philosophy?" in five parts:

1. Philosophy and Higher Education

2. Benefits of the Philosophical Mindset

3. Benefits Through the Sciences

4. Benefit to Society

5. Benefit to the Individual

1. Philosophy and Higher Education

Recall that philosophy is the pursuit of truths that cannot be wholly determined empirically. Philosophy pursues wisdom, and is

therefore crucial in defining methods for the development and refinement of knowledge in all fields. As a result, philosophy is nearly

synonymous with higher learning. Indeed, the words “academia” and “academic” come from the name of Plato’s school of philosophy,

the Academy. The highest degree attainable in academia is the PhD, Latin for philosophiae doctor, or doctor of philosophy.

Philosophy

The pursuit of truths that cannot be wholly determined empirically.

Asking “why care about philosophy” is like asking “why care about higher education?” Philosophy is a collegiate activity that signifies

intellectual maturity. One can question the status quo — not to be belligerent, but out of a genuine desire to understand it. All you have

learned previously becomes a starting point, not an end.

2. Benefits of the Philosophical Mindset

In enumerating the advantages of philosophy, 20th century philosopher Bertrand Russell pointed out that it enlarges our thoughts and

frees us from the “tyranny of custom.” How does philosophy do this? By asking “why” questions, and determining whether the answers

are satisfactory. Philosophy requires that all beliefs be justified. What does this mean?

State a belief: “I believe (fill in the blank) is true.” Next, ask “why” you believe what you've stated. Why do you think your belief is

true? If you can provide a good answer, one that is good enough to convince a reasonable skeptic, then you have justified your belief

and, therefore, know it. If you cannot provide an answer, or only an answer that a skeptic would find unsatisfactory, you have an

opinion, but do not know. You should not believe what you

've stated, or should believe it only provisionally.

Philosophy's requirement that beliefs must be justified leads to regular questioning of beliefs and refinement of answers.

For thousands of years, people believed that only certain organic matter (composted plants and excrement) were

adequate fertilizers. In the 20th century, someone finally asked the crucial question: “Why do we think that we can only use organic

matter as fertilizer?” No one could provide a good answer to this question. What people had believed for thousands of years was

opinion, not knowledge — something handed down through generations of farmers. It was Russell’s “tyranny of custom.” When freed

from this tyranny, scientists developed nitrogen-based fertilizers, more land was farmed, and every acre produced more crops.

Millions of people were spared famine and starvation, thanks to the philosophical mindset and its determination to hold only justified

beliefs.

This is only one example, but it represents how progress has taken place over the centuries.

3. Benefits Through the Sciences

As the last example demonstrated, the philosophical mindset is key to progress in the sciences. However, the connection between

philosophy and science is deeper than that.

© 2018 SOPHIA Learning, LLC. SOPHIA is a registered trademark of SOPHIA Learning, LLC. Page 5Philosophers have made the significant contributions to scientific methodology, and have contributed to the formation of science as we

know it today. Epistemology set the standards of knowledge, and the philosophy of science developed methods to attain it. Aristotle, a

Greek philosopher, is considered to be the father of physics and biology. He contributed to the development of the foundations of

science. His concepts were later refined and incorporated into the modern scientific method by Francis Bacon, who was also a

philosopher.

Epistemology

The branch of philosophy that analyzes and defends concepts of knowledge and the methodologies used to attain it.

Images of Aristotle and Francis Bacon

Philosophy has inspired breakthroughs in theoretical science. Isaac Newton’s Principia is, in part, a text on natural philosophy. Albert

Einstein cites the work of philosopher David Hume as the primary influence on his development of the Theory of Relativity. Hume’s

work also inspired much of Adam Smith’s economics.

Many philosophers were also mathematicians and/or scientists, including René Descartes (perhaps you have heard of Cartesian

coordinates), and G.W. Leibniz, who developed the binary number system and symbolic logic, without which we would not have

computers. When someone’s passion is knowledge, and that knowledge is groundbreaking, distinctions between philosophy and

theoretical science disappear.

4. Benefit to Society

Although you may have hesitated to give philosophy any credit for developments in theoretical science, you need only look around you

to see what it has done in ethics and political philosophy. As a result of its influence in these areas, philosophy has led to improvements

in society and culture.

The U.S. Constitution, including much of the Bill of Rights, is based on the political philosophy of John Locke. Many of the Founding

Fathers were Lockeans.

General acceptance of democracy as the fairest form of government was a philosophical development. Similarly, most of our modern

© 2018 SOPHIA Learning, LLC. SOPHIA is a registered trademark of SOPHIA Learning, LLC. Page 6concepts and advancements with respect to justice, fairness, and equality originated with political philosophers. If you appreciate the

end of slavery, the fight for racial equality, women’s suffrage, or other instances of social progress, thank a philosopher.

Philosophy has also contributed to advancement in ethics. Philosophers are often employed as consultants on hospital ethics boards, as

well as in other fields of applied ethics including environmental and business ethics. Philosophy has influenced societies' views on right

and wrong for millennia.

5. Benefit to the Individual

Do you think you would benefit from being wiser? More moral? A better critical thinker? Being better equipped to distinguish

knowledge from opinion? Making decisions based on reason instead of emotion? Acting according to your beliefs? Having a consistent

worldview? Recognizing value? Minimizing bias while maximizing objectivity?

The study of philosophy does all this and more. It makes you a better person, but it can also have more immediate, tangible results. The

study of philosophy has been shown to increase standardized test scores and performance in other courses. And, despite opinions to

the contrary, philosophy degrees are highly sought by business employers because "thinking outside the box" is vital to business

solutions and strategy.

Like your other courses, you will get out what you put into a philosophy class. If you make an effort in "Ancient Greek Philosophers,"

you will be rewarded.

Philosophy brings value from the global level to the individual. A philosophical mindset is required for any sort of progress.

Philosophy has advanced (and continues to advance) the sciences; it has contributed to the growth of more ethical and just

societies; and has broadened and improved the minds of those who study it.

Source: Image of Aristotle, PD, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Aristotle#/media/File:Aristotle_Altemps_Inv8575.jpg, Image of Francis

Bacon, PD https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Francis_Bacon#/media/File:Pourbus_Francis_Bacon.jpg

TERMS TO KNOW

Epistemology

The branch of philosophy that analyzes and defends concepts of knowledge and the methodologies that attain it

Philosophy

The pursuit of truths that cannot be wholly determined empirically

© 2018 SOPHIA Learning, LLC. SOPHIA is a registered trademark of SOPHIA Learning, LLC. Page 7Cosmology and the First Philosophers

by Sophia Tutorial

In this section, we will examine the very first western philosophers, the Pre-Socratics. After discussing why they are considered

philosophers, we'll learn about some of the major figures and their ideas, and how those ideas shaped the world as we know it.

This tutorial examines Cosmology and the first philosophers in three parts:

1. Who Were the Pre-Socratic Philosophers?

2. Some Pre-Socratic Philosophers and their Influential Ideas

3. Intellectual Legacy of the Pre-Socratics

1. Who Were the Pre-Socratic Philosophers?

A group of philosophers now known as the Pre-Socratics were active In Greece between (approximately) 600- 450 BCE.

Pre-Socratics

A collective term used for Greek philosophers who practiced philosophy before Socrates

The influence of the Pre-Socratics is limited because most of their work has not survived. What remains of their beliefs and teachings

are fragmenta: mostly quotations from other philosophers whose works were preserved, and testamonia: references to them and their

work (but not quotations) in other ancient texts. Our access to their work, therefore, is limited, but their work remains important. They

influenced and inspired those whose ideas changed our science, culture and intellectual traditions. They were true philosophers, even

though what we know about them and their work is limited to their major ideas.

They are categorized as Pre-Socratics, not only because of their limited influence, but also because much of their work can be assigned

to natural philosophy or cosmology, branches of philosophy that have been largely relegated to the sciences.

Natural Philosophy

The branch of philosophy that considers nature and the universe

Cosmology

The branch of philosophy that considers the universe in its totality

Natural philosophy has moved from being a branch of philosophy to an area that is studied in physics, astronomy, and other sciences.

Cosmology is now a branch of astrophysics (cosmogony is a branch of cosmology that focuses on the origin of the universe). When we

take this into account, we can see that the Pre-Socratics were practicing theoretical science when science was still part of philosophy.

Why then was their work once considered philosophy? To answer this question, recall that philosophy is the pursuit of truths that cannot

be determined empirically. Questions like, “what are stars made of” could not be answered empirically 2,500 years ago. The theories,

discoveries, and tools required to answer those questions had not been developed. All that the Pre-Socratics had to work with was their

observations, and what they could conclude based on those observations.

Their methodology was philosophical in two ways: First, they used argument and reason to identify the best answers to the questions.

Second, their methodology was naturalistic. They did not rely on divine mechanisms to support their answers. Also, they did not only

work on these topics. Their findings in natural philosophy influenced their views in other areas of philosophical inquiry.

2. Some Pre-Socratic Philosophers and their Influential

Ideas

Following is a list of some of the most influential Pre-Socratic philosophers, and their major ideas. The list is a sample; it is not

comprehensive. Two significant Pre-Socratics, Heraclitus of Ephesus and Parmenides of Elea, have been omitted because they will be

examined in detail in separate tutorials.

The Milesians

This group, usually considered to be the first Pre-Socratic philosophers, consisted of Thales and his pupils, Anaximander and

Anaximenes. It was said that Thales claimed that everything in the cosmos was made of water, but Anaximenes held that everything was

made of air. Anaximander maintained that the cosmos was initially apeiron (i.e., “boundless” or “without qualities”), but became

© 2018 SOPHIA Learning, LLC. SOPHIA is a registered trademark of SOPHIA Learning, LLC. Page 8differentiated.

If these theories seem far fetched, note that their methodology was sound. These philosophers used empirical data (i.e., information

obtained by observation) to formulate theories of reality that best fit that data.

What these three theories have in common was the positing of a single cosmos: the claim that all matter was united according to a single

arrangement/order, governed by universal laws. This was the Milesians’ true philosophico-scientific advancement. They were

essentially correct in taking this position. Science worked out the details over the next 2,500 years.

Pythagoras

Pythagoras (long thought to be the discoverer of the Pythagorean Theorem) and his followers incorporated mathematics into his

philosophical worldview.

The Pythagorean Theorem, a basic component of algebra courses today, has been around for thousands of years!

To the Pythagoreans, the world was a mathematical entity of perfect harmony. They assigned great importance to certain numbers found

in nature (e.g., the number of heavenly bodies). A human’s job was to find his or her proper place in this harmonious system. They also

formulated and defended a reincarnation doctrine related to their worldview.

Xenophanes of Colophon

Xenophanes, a travelling poet, was also a philosopher who lived to great age. Secularization played a major role in his philosophy. He

reassigned divine mechanisms to naturalistic causes, such as the rainbow, which ancient Greeks believed to be a manifestation of the

messenger goddess Iris. Xenophanes identified rainbows as phenomena produced as a result of meteorological causes.

Xenophanes maintained that it is better to rely on observation and reason than on signs from the gods. He was not an atheist, but

objected to then-common conceptions of the gods, faulting earlier poets for depicting deities as treacherous and deceitful beings who .

constantly interfered in human affairs. He also opposed theories that relied on “the god of the gaps,” in which a miracle is used to

support an otherwise-scientific explanation because there was no known natural cause. To Xenophanes, the gods controlled all things,

but acted predictably, not miraculously. Indeed, science is close to impossible if gods constantly interfere with natural phenomena.

Xenophanes characterized this as anthropomorphism — the application of human attributes to something that is non-human (like the

gods). In some ways, the Greek gods were depicted as the worst of humans. Zeus used his powers to change his form and rape women.

Hera, his wife, punished those women. The gods sometimes helped the strong to defeat the weak, and the unreasonable to kill the

reasonable. As depicted, the gods often behaved in ways that humans might behave if they had divine power. In these depictions,

therefore, humans projected their attributes onto the gods. As Heraclitus stated:

© 2018 SOPHIA Learning, LLC. SOPHIA is a registered trademark of SOPHIA Learning, LLC. Page 9Any gods worth their titles would be the authors of the laws of nature. Their actions in the world would take place through nature, not

above and beyond it.

Anaxagoras of Clazomenae

Anaxagoras was primarily interested in cosmology. Denying that celestial bodies were gods, he interpreted the world around him in

natural terms, and formulated one of the first cosmogonies. Before there was a known universe, he theorized that everything began as

an undistinguished mixture that took form and definition when a force called nous began to spin the mixture. The literal translation of

nous is “mind,” but ancient Greek had such a small vocabulary that a word was often used for several things. As a result, it is not clear

whether Anaxagoras defined nous as a deity or as a force of order (like the laws of nature). Either way, nous is the force which gives

form to the universe, a process which Anaxagoras believed to be ongoing. He was condemned in Athens for maintaining this naturalistic

concept.

Empedocles of Acragas

Empedocles was a physicist who was deeply religious. He was probably a Pythagorean. As a physicist, Empedocles maintained that

there were four “roots” — what Aristotle would later call the elements — earth, air, fire, and water. These were combined by love, and

separated by strife. In this system, there were six metaphysical entities that formed everything in the cosmos. Instead of coming into

existence and passing away, Empedocles viewed the universe in terms of mixing and separating. (He thought this process also occurred

on the physical level, involving the flow of blood.) He was concerned with religious purity and purification, and defended the

Pythagorean notion of reincarnation.

Protagoras of Adera

Protagoras was a member of the “Older Sophists,” a group of traveling intellectuals. He made two significant intellectual contributions,

which are interrelated. Protagoras was perhaps the first outspoken agnostic. He argued that we could not know whether the gods

existed or not. This led him to make a second claim: “man is the measure of all things.” This statement is usually interpreted to mean that

knowledge is relative to the knower. This implies that we cannot escape our biased perspective. We cannot know what it is like to walk

in another person’s shoes.

3. Intellectual Legacy of the Pre-Socratics

It might be tempting to dismiss some of the ideas of the Pre-Socratics as quaint and outdated, but they mark the beginning of science.

By observing the natural world and using reason to explain phenomena, the Pre-Socratics' provided a basis for all subsequent advances

in the sciences.

Notice that there are common themes shared by the Pre-Socratic philosphers. The first is a consistent worldview, in which one or a few

laws and elements are used to account for a variety of phenomena. The second is methodological naturalism. Most Pre-Socratics did not

deny the existence of the gods, but maintained that we should not invoke them to explain phenomena. This (as a method, not with

respect to belief) has enabled scientific progress from their time until the present day.

The Pre-Socratics viewed natural philosophy and theology as separate disciplines, with different standards of knowledge, and different

applications. Their commitment to natural philosophy enabled them to think in new ways. In a number of areas, it took science millennia

to catch up with them (e.g., thought described as a result of physical processes; Anaximander hinting that humans evolved from lower

animals).

The Pre-Socratics were the first Western philosophers. In this tutorial, we examined the contributions of some of the most

influential philosophers in this group. The Pre-Socratics took a philosophical approach to questions that are now of interest to the

sciences. Their ideas were a starting point for philosophic and scientific investigation.

Source: Heraclitus image, PD, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Heraclitus#/media/File:Hendrik_ter_Brugghen_-_Heraclitus.jpg

TERMS TO KNOW

Cosmology

The branch of philosophy that treats the origin of the universe in its totality

Natural Philosophy

The branch of philosophy that treats nature and the universe

Pre-Socratics

A collective term for the group of Greek philosophers practicing philosophy before the influence of Socrates

© 2018 SOPHIA Learning, LLC. SOPHIA is a registered trademark of SOPHIA Learning, LLC. Page 10The Atomistic Worldview

by Sophia Tutorial

In this lecture, we will examine the notion of a philosophical worldview, and present an influential worldview from ancient Greece:

philosophical atomism.

This tutorial investigates the philosophical worldview and atomism, in three parts:

1. Philosophy as a Worldview

2. The Atomistic Worldview

3. Atomistic Influence

1. Philosophy as a Worldview

Perhaps you have been asked, “What is your philosophy?” In light of our definition of philosophy — the pursuit of truths that cannot be

wholly determined empirically — you may find this question difficult to answer. However, the question and our definition may be more

closely related than they seem to be. Since metaphysics, a branch of philosophy, considers first principles and the ultimate components

of reality, there is a sense in which everything falls within the purview of philosophy.

A cohesive and defensible system of metaphysics enables provides one with a way to interpret reality — a worldview. For example, if

you answer “what is your philosophy?” by stating your belief that physical reality is the only reality, your answer impacts on how you

view the world. As a result of your answer, you must reject or radically reinterpret religion and belief in a deity. You must also interpret

thought as a purely physical phenomenon, and deny the existence of a brain-independent mind or soul. You must likewise take a

position on other abstract entities that many people believe exist.

Numbers are abstract entities that many people believe exist independent of the human mind. If your philosophy only

allows for physical entities, you must reject the existence of mind-independent numbers, since they are not physical things. (You

would also have to equate “mind” with part of the brain.)

Lastly, you must ensure that your actions are consistent with your beliefs. Hence, in developing a metaphysical view, you have also

developed a worldview.

2. The Atomistic Worldview

An early and extremely influential worldview was developed by the ancient Greek atomists. According to atomism, reality is composed

of atoms in a void.

The word "atom" comes from the Greek atomon, which means "uncuttable." An atom, therefore, is matter which is indivisible and without

parts. This is not the definition of atom used in contemporary chemistry and physics. We now know that atoms are divisible and have

parts (i.e., subatomic particles).

At the time when these atoms (think of them as “chemical atoms”) were discovered, scientists thought they had found a basic, indivisible

entity, so they took the name from ancient Greek philosophy and applied it to their discovery. It was later determined that chemical

atoms are divisible, but the name (i.e., atom) continues to be used. As a result, we must distinguish a philosophical atom from a

chemical atom.

Philosophical Atom

An indivisible physical entity

Since chemical atoms do not fit this description, they are not the same as philosophical atoms.

The chief defenders of philosophical atomism in ancient Greece were Leucippus and his student Democritus. It is through the latter that

we have received most of what we know about ancient Greek atomism. (It is important to note that, in addition to Greek atomism, there

were other ancient atomist philosophies, including Indian and Islamic traditions.)

Greek atomism states that everything that exists is either an atom or a collection of atoms. Atoms are the smallest entity, but they are

not infinitely small. Aristotle, when attempting to solve one of Parmenides’ (another philosopher) metaphysical puzzles involving

change, referred to the atomistic view that new things don’t come into existence. Instead, existing things change their organization: they

take new forms.

© 2018 SOPHIA Learning, LLC. SOPHIA is a registered trademark of SOPHIA Learning, LLC. Page 11Have you ever seen something begin to exist? Matter doesn’t seem to come into being. It only seems to change form. Consider, for

instance, a human coming into being. The cellular material doesn’t come from nowhere. It comes from nutrients consumed and

processed by the mother. Matter (the nutrients) is reordered into a new form (a human).

The atomists believed that there were different kinds of atoms. They came in different shapes and sizes, and could be combined in a

variety of ways. In the atomistic view, different atomic textures were used to explain how different sensations were produced. Different

bonding configurations accounted for the degree of solidity of objects and other phenomena. Since, at that time, action at a distance was

believed to be impossible, the atomist account was used to solve other puzzles (as in the following example).

The ability to perceive odors — to smell — was explained as the transfer of atoms from an object into the nose.

Different shapes and configurations of atoms produced a variety of smells.

It is important to note that the atomist philosophy is rich in explanations. Starting with a few simple assumptions, the atomists described

and explained a variety of complex phenomenon.

3. Atomistic Influence

As was the case with the work of the Pre-Socratics in natural philosophy, science has had to "catch up" with philosophy. With some

revisions (including how molecules form bonds), the atomist worldview has been adopted by contemporary science.

However, it is important to keep in mind that, in addition to its influence on the sciences, atomism is a philosophical worldview, and that

worldviews impact your perception of reality. The natural explanations for phenomena provided by philosophical atomism provoked

religious and theological responses. Some theologians viewed atomism as an attack on religious belief. Others embraced it. In general,

the worldview provided by Greek atomism, which is rich in satisfactory explanations of reality, requires us to consider, and even

accommodate it. We are compelled to incorporate the tenets of atomism into our own worldviews, just as we are obliged to incorporate

contemporary breakthroughs in physics and astrophysics.

Ancient Greek atomism is an example of a successful worldview. It provides a metaphysical system that is defensible and rich in

explanations of phenomena. It is based on a belief in philosophical atoms of different qualities (e.g., shape, texture) that are the

fundamental components of reality.

TERMS TO KNOW

Philosophical Atom

An indivisible physical entity

© 2018 SOPHIA Learning, LLC. SOPHIA is a registered trademark of SOPHIA Learning, LLC. Page 12Parmenides and the Doctrine of Permanence

by Sophia Tutorial

Parmenides of Elea was an influential Pre-Socratic philosopher, often considered the father of metaphysics. He and his school had

a profound impact on later philosophy, especially that of Plato. Though, as with other Pre-Socratics, we have only fragments and

testemonia of his philosophy, they indicate that he was an original thinker. What remains of Parmenides' work is part of a single,

extended metaphysical poem in which a student travels to meet a goddess, who lectures him about truth and belief. The proper

interpretation of the poem has been the subject of scholarly debate. In this tutorial, Parmenides' ideas regarding "the turn to

metaphysics," and his doctrine that the universe is one, unchanging entity, will be examined.

This tutorial investigates the philosophy of Parmenides, including the doctrine of permanence, in three parts:

1. The Turn to Metaphysics

2. The Doctrine of the Unchanging One

3. Zeno’s Paradoxes

1. The Turn to Metaphysics

Parmenides was deeply influenced by Xenophanes (Parmenides may have been his student). Recall that Xenophanes criticized the prephilosophical tradition of relying on the gods to explain natural phenomena. Xenophanes maintained that there was a strict division

between mortal and divine knowledge that cannot be crossed. Parmenides upheld this distinction, but went even further by claiming that

the opinions of mortals are universally unreliable.

If mortals do not have access to divinity, but cannot attain knowledge without divine aid, how can they move beyond their flawed

opinions and discover the nature of reality? Parmenides' answer is that there are signs we can follow, which point to genuine reality:

signs that "turn to metaphysics."

Recall that metaphysics seeks to uncover and describe the ultimate nature of reality. In this context, it is a quest to look beyond the

mortal world, the world of the senses and of unreliable opinion, to perceive reality as it truly is. Metaphysics is the answer to how

humans can take a god’s-eye view and discover what is real.

Metaphysics

The branch of philosophy that seeks to uncover and describe the ultimate nature of reality

2. The Doctrine of the Unchanging One

Substance monism is a component of Parmenides’ metaphysics, that has been attributed to him by later sources. It is the view that all of

reality is one object, usually translated as the “what-is.” The "what-is" is a term for the way things are: The True. Parmenides also posited

a corresponding “what-is-not.” This can be thought of as The False. Together, these two concepts create a duality in Parmenidean

metaphysics.

In this metaphysical system, what-is, is, but what-is-not, cannot be. That this must be so becomes evident when basic questions are

asked: where would what-is-not come from? How would it come into being?

What-is-not cannot come from what-is. The False cannot come from The True. Non-being cannot come from being. However, it is also

impossible for what-is-not to come from nothing, since nothing cannot produce anything. As a result, the universe cannot change from

what-is to what-is-not. If "The True" is true, it cannot become "The False." At the same time, what-is cannot cease to be, since

transformation from being to non-being is metaphysically impossible, according to Parmenides.

In this system, what-is is eternal and unchanging, because change would require the universe to pass from what-is to what-is-not.

Although this is the conclusion to which Parmenides’ metaphysical analysis leads, it is not the universe with which we are familiar. Our

universe is changing and impermanent. This creates a duality between the genuine, unchanging realm of reality, and the changing world

of appearance. Parmenides’ way focuses on the former, but the way of opinion, in which observers do not realize that this transient

world of change is illusory, is focused on the latter.

What are some advantages in seeing the world as unchanging? How might they account for our ability to know and learn?

3. Zeno’s Paradoxes

© 2018 SOPHIA Learning, LLC. SOPHIA is a registered trademark of SOPHIA Learning, LLC. Page 13Maintaining that change is illusory, as Parmenides does, seems to run counter to common sense. You may be tempted to dismiss

Parmenides’ view for that reason alone, but you would be wise to avoid a quick dismissal of his conclusions. Think about all of the things

we know are true, despite what "common sense" tells us.

Right now, you are moving at 67,000 miles per hour while standing on a round surface that is rotating at up to 1,000

miles per hour. Space itself is expanding, and it curves around heavy objects.

These examples show that “strange” cannot be equated with “false.” This is especially true when you are forced to choose between

two peculiar options. For example, when you think about the origin of the universe, it seems as if you must choose between a Big Bang,

in which all matter in the universe comes randomly into being, and a creator god who waited for an infinity before deciding to create the

cosmos 13 billion years ago. In this debate, one side calling the other’s view “strange” is a case of the pot calling the kettle black. Such

accusations are not significant challenges to any view. When considering big questions, things sometimes get weird.

One of Parmenides’ most famous students, Zeno of Elea, wrote a short book describing paradoxes. He demonstrated that motion was

a far stranger phenomenon than the "commonsense" view of it held by most people would allow. By doing so, Zeno showed that

rejection of Parmenides’ explanations of how things work simply because they're "strange," and because they refuted "commonsense"

opinions based on what seemed to be obvious and apparent, was illegitimate criticism.

Paradox

Situations in which seemingly reasonable assumptions lead to a contradiction or an absurdity

Consider this claim: “This sentence is false.” This claim seems reasonable because it is presented in the same structure as many claims

we make. However, if the sentence is true, then it’s false; if it’s false, then it’s true! Instead of describing contradictions, Zeno’s

paradoxes of motion show that simple assumptions about motion lead to absurdity.

There are many kinds of paradoxes, as a result of how slippery the notion of “absurdity” is (e.g., is the presence of absence an

absurdity?). “Paradox” covers a large number of logical and metaphysical oddities. Socrates and Plato, who we'll discuss later in this

course, emphasized precise definition of important words including “justice,” “craft,” and “piety.” They believed that precise definitions

were required in order to be clear about the concepts being discussed. However, it can be difficult to define terms like these with

precision. In contrast, the oddities uncovered by Zeno are relatively straightforward.

Zeno explained a number of paradoxes, but only a few of them have been preserved. His paradoxes of motion fall into two categories:

those which demonstrate the difficulties involved in positing time as a continuum, and those which demonstrate the difficulties involved

in positing time as being composed of discrete moments.

To argue against a continuum, Zeno raises considerations which include the following:

If time is a continuum, how could we ever get from one place to another? To move from A to B, we must first halve the distance, then

halve it again, then halve it again, and so on. That is, we must complete an infinite task through a series of finite actions.

If you haven't grasped this paradox yet, imagine an additional feature: a light turns on when you move half the distance from A to B. It

turns off when you halve it again, and so on. When you finally arrive at B, is the light on or off?

To argue against a discrete notion of time, imagine an arrow being fired. Consider one point in time (i.e., one moment), and label it T1. At

time T1, the arrow will have a specific position, P1. At the next moment, T2, the arrow has moved to a new position, P2. When did the

motion occur? Between moments? There is no such thing as "between moments," if time is discrete. If we assume that time is composed

of discrete moments, the arrow didn’t move, even though it is no longer at P1, but is now at P2. This is also absurd.

© 2018 SOPHIA Learning, LLC. SOPHIA is a registered trademark of SOPHIA Learning, LLC. Page 14Parmenides saw metaphysics as a way to transcend opinion and examine the world as it really is. But his analysis, based on the use

of reason, led him to conclude that this world is unchanging, unified, and eternal. Such a world does not correspond to the world of

appearances, which means that the latter is an illusion. Zeno modified this extreme claim by pointing out some of the strange

features of the illusion.

Source: Archer by damar bintang from the Noun Project (CC), bullseye by Dinosoft Labs from the Noun Project (CC), Arrow by Valeriy

from the Noun Project (CC). All retrieved from The Noun Project :www.thenounproject.com

TERMS TO KNOW

Metaphysics

The branch of philosophy that seeks to uncover and describe the ultimate nature of reality

Paradox

When seemingly reasonable assumptions lead to either a contradiction or an absurdity

© 2018 SOPHIA Learning, LLC. SOPHIA is a registered trademark of SOPHIA Learning, LLC. Page 15Heraclitus and the Doctrine of Impermanence

by Sophia Tutorial

Heraclitus of Ephesus was another influential Pre-Socratic philosopher. Like Parmenides, he was interested in metaphysics and

the realm of appearances, and thought that the gods could not guide humans in these areas. However, he reached some

conclusions that differed greatly from those reached by Parmenides, arguing that the impermanence of the world of the senses

was the true nature of reality.

This tutorial examines Heraclitus and impermanence in three parts:

1. Heraclitus on the Secular

2. Heraclean Flux and the Unity of Opposites

3. Parmenides and Heraclitus

1. Heraclitus on the Secular

Though he was not affiliated with any philosophical school, Heraclitus, like Parmenides, was influenced by the rational theology

established by Xenophanes. Recall that Xenophanes disparaged the practice of turning the gods into fickle meddlers in human affairs,

and thought that actions taken by the gods were constant (i.e., according to the laws of nature). Heraclitus went further than his

predecessors by emphasizing the human role in affairs. His approach to reality was entirely secular. He maintained that there was one

true version of reality which he called the Logos.

The Greek word “logos” is translated as “account.” Hence, “biology” means to give an account of life. Logos was translated by

ancient Greek Christians as "the Word," as in, “in the beginning was the Word” — a surprisingly Heraclitean notion.

Heraclitus believed that the Logos governed and/or organized all things, and.that it did so independently — without the participation of

the gods. Although it is not clear whether he intended Logos to be distinct from reality (like a god), or dispersed through everything in

the universe, all things in the cosmos are unified according to the Logos.

The Logos belongs in the realm of metaphysics because it is not in the world we experience, but underlies it. Though difficult to

understand, the "Logos" can be comprehended by humans, even though not all of them are capable of grasping it. The Logos is always

true, whether anyone is aware of its reality or not. It is independent of knowledge and language, and belongs in the realm of

metaphysics.

2. Heraclitean Flux and the Unity of Opposites

The two most significant principles through which Heraclitus’ Logos governs are the Unity of Opposites and the Doctrine of Flux.

The Unity of Opposites is an assumption that the world is composed of opposites, and that opposites are linked in a system of

connections.

There cannot be a mountain without a valley, and vice-versa. People cannot awaken if they have not first been asleep,

and vice versa. Things are linked to what they are not. Heraclitus points out, for example, that ocean water is toxic to humans but

necessary for fish. The opposite is true of fresh water.

Can you think of more unities of opposites? One that is frequently cited, especially in the philosophy of religion, is the importance of

good and evil. Do you think this is a unity of opposites? Why or why not?

Beyond simply pointing out these unities, Heraclitus locates them inside us. He maintains that youth and age, life and death, are already

within us. One quality becomes the other. Each of them changes into its opposite — young becomes old, life becomes death, healthy

becomes ill.

Human beings occupy a privileged position in the universe according to Heraclitus. He indicates that our souls are connected to the

Logos through language, a human phenomenon.

Heraclitus’ Doctrine of the Flux is closely related to the unity of opposites. It states that all things change over time. Everything is

impermanent, and is in a constant state of change, moving from what it is to what it is not. He famously declared that you cannot step into

the same river twice, since, as water passes ceaselessly, the river becomes new. (The Heraclitans later pointed out that you cannot step

into the same river once.) You are not the same person you were yesterday.

© 2018 SOPHIA Learning, LLC. SOPHIA is a registered trademark of SOPHIA Learning, LLC. Page 16Have you encountered anything in the world (other than metaphysical objects, such as numbers, laws of nature, etc.) that does not

change?

Heraclitus holds that change is the ultimate nature of reality. All is flux. However, when reading the philosophy of Heraclitus, we must be

careful to avoid taking some statements too literally. For example, Heraclitus' assertion regarding change is sometimes translated as a

claim that all is fire. This should be read metaphorically, and in light of the rest of the text. Fire flickers, and in doing so it changes

constantly. Saying that all is fire is a metaphorical way of saying that all is changing.

The metaphorical use of words — like using “fire” for “change” — was common in ancient Greek writing, because the language had a

small vocabulary.

3. Parmenides and Heraclitus

Recall that Parmenides claimed that the ultimate nature of reality is static, and that change is illusory. Heraclitus, on the other hand,

asserted that the ultimate nature of reality is change. It may be tempting to view them as polar opposites, philosophically speaking. In

doing so, however, we would ignore significant points on which they agree.

Both Parmenides and Heraclitus join Xenophanes in turning from divine causation and oracular knowledge to a secular concept of

reality. For both of them, this involved examination of what is universal and regular in nature, rather than what is random. Both of them

studied metaphysics, searching for the first principles and the ultimate nature of reality. They both recognized that the world of

appearances is in constant flux, and that it is impermanent.

Parmenides and Heraclitus believed that something constant underlies the impermanent world of change. Parmenides identified it as the

realm of being, the realm of what-is Heraclitus posited a Logos that contains the universal principles of the Doctrine of Flux and the

Unity of Opposites.

What is the significant difference between the philosophy of Parmenides, and that of Heraclitus? It seems to be the status of change.

Parmenides states that change is illusory, while Heraclitus claims that change is not only genuine, but essential to reality.

© 2018 SOPHIA Learning, LLC. SOPHIA is a registered trademark of SOPHIA Learning, LLC. Page 17Do you agree with Heraclitus or Parmenides? Start by answering a smaller question: Which of the following is more important to

reality: what changes, or what is permanent? If you believe that reality is somehow a combination of the two, you will begin to see the

metaphysical problem that Plato inherited, and some of what underlies his philosophy. We will investigate Plato and his solution in a

subsequent tutorial.

Heraclitus, like Parmenides, was interested in metaphysics as a way to examine the true nature of reality without involving the

gods. He maintained that a Logos governs all things, and does so via the Unity of Opposites and the constancy of Flux. Although his

philosophy is in some ways similar to that of Parmenides, they are ultimately at odds regarding the ultimate status of change —

essential or illusory.

© 2018 SOPHIA Learning, LLC. SOPHIA is a registered trademark of SOPHIA Learning, LLC. Page 18Socrates: The Father of Western Philosophy

by Sophia Tutorial

Socrates (circa 470-399 BCE) was one of the most important philosophers of all time. Although he was not the first western

philosopher, he is known as the “Father of Western Philosophy.” This is not only because of his influence on other significant

historical figures, but also because he re-oriented philosophy to focus on the areas studied today. He was completely dedicated

to living his philosophy, even though it cost him his life.

This tutorial investigates Socrates' life and work in four parts:

1. Socrates, Patriarch of Western Thought

2. Socrates, Seeker of Wisdom

3. The First Step on the Path to Wisdom

4. Socrates, a Martyr for Wisdom

1. Socrates, Patriarch of Western Thought

Socrates lived until the age of 70. For most of his adult life, he was a teacher of philosophy. He did not charge tuition, but his ability,

wisdom, and pedagogy attracted Athenian pupils, many of whom came from wealthy and noble families. One of these pupils was

Aristocles, better known as Plato.

© 2018 SOPHIA Learning, LLC. SOPHIA is a registered trademark of SOPHIA Learning, LLC. Page 19Bust of Socrates in the Vatican Museum

Socrates taught Plato philosophy: not only how to seek wisdom, but also its importance. Plato started the Academy (and, arguably,

higher education), and laid the foundations for western philosophy (and, perhaps, theology and political science). Plato’s influence and

accomplishments were vast, but some portion the accolades he receives belongs to Socrates.

Plato also taught an important pupil: Aristotle. Aristotle was a philosopher and a scientist. He may have done more to advance science

than anyone else. He is known as the father of physics, biology, and logic, and was a major contributor to the development of western

thought. His work influenced the doctrine of the medieval Catholic Church, and was disseminated throughout the western world as a

result.

Like Plato, Aristotle's accomplishments and influence cannot be overstated. However, he could not have achieved what he did without

his teacher, Plato, and Plato's teacher, Socrates. These philosophers and their accomplishments are discussed in more detail in later

tutorials.

It is in no way an exaggeration to say that Socrates was one of the most influential people in history. Like some of the other significant

ancient thinkers, he did not produce any written work. The accounts we have of his life and teachings were primarily recorded by Plato.

© 2018 SOPHIA Learning, LLC. SOPHIA is a registered trademark of SOPHIA Learning, LLC. Page 202. Socrates, Seeker of Wisdom

Socrates' historical influence has continued to this day, but it is important to understand that, during his life, he oriented philosophy in

new directions. Recall that the Pre-Socratics were given their name because their methods, and the topics they investigated, were

different than those that are the focus of contemporary philosophy. Socrates redirected philosophy to consider topics that are studied

to this day.

The Pre-Socratic philosophers primarily studied cosmology and natural philosophy, fields that were later appropriated by the sciences.

Ethics and epistemology, on the other hand, have not (and probably cannot) be appropriated by other fields of study. These were the

topics of greatest importance to Socrates. He sought wisdom. How to live according to ethical principles, and how to differentiate

knowledge from opinion, were questions that must be answered to attain true wisdom. Socrates was the first moral philosopher, and the

first epistemologist.

Epistemology

The branch of philosophy that analyzes and defends concepts of knowledge and the methodologies used to attain it

Ethics

The branch of philosophy that analyzes and defends concepts of value and thereby seeks to determine right and wrong

Though all of these thinkers investigated many areas of philosophy, the ways in which Socrates changed the direction of philosophy

can be simplified as follows:

Pre-Socratics’ Primary Focus Socrates’ Primary Focus

Key areas of philosophy Cosmology and Natural Philosophy Ethics and Epistemology

The most important philosophical questions What is real?

What is the nature of the universe?

What is knowledge?

What is right?

What is the good life and how should I live?

3. The First Step on the Path to Wisdom

How did Socrates distinguish knowledge from opinion? First, it is a distinction in belief. But secondly, the distinction is not in what you

believe, but in why you believe it. Two people can believe the same thing, but one knows why he or she believes; the other merely

believes.

What’s the difference? The answer involves the all-important philosophical question — why? If you ask someone, “why do you believe

x?”, and he or she provides a reasonable answer that is grounded in fact, that person knows x. If you ask why, and receive no answer, or

a bad answer (i.e., one that is not grounded in reason or fact), that person has an opinion about x, but does not know it..

© 2018 SOPHIA Learning, LLC. SOPHIA is a registered trademark of SOPHIA Learning, LLC. Page 21Here are some of the most common sources of bad answers:

Source Example Why it falls short of knowledge

Belief based on

falsities

I think we should keep capital

punishment because it saves money.

This is opinion, not knowledge, because it costs far more to execute

someone than to imprison him/her for life.

Belief based on

tradition/culture

I think that a certain race is inferior

because that’s what people previously

believed or that’s what my parents told

me.

This is opinion, not knowledge, because the statement is not grounded in

fact or reason.

Belief based on

false authority

I believe this about the economy

because a celebrity said so, or I

believe that about climate change

because a politician (or lobbyist) said

so.

The celebrity may very well be right, but that does not justify the belief.

This person has an opinion about climate change, rather than knowledge

on this topic. Difficult subjects require expertise, not hearsay.

Belief based on

confirmation

bias

I believe there is an afterlife because I

cannot bear to think of death as the

end.

A well-documented fact about human psychology is that we lower our

evidentiary standards when we like the conclusion. We raise them when

we dislike the conclusion. “I want x to be true, therefore, x is true” is an

invalid, and sometimes dangerous, inference.

Think of answers to “why” questions that fall into these four categories.

First, think of examples of each in politics or a national issue.

Next, think of personal examples of each (e.g., people you have interacted with in your family or on social media).

See if you can do what Socrates requires — to shift from thinking about these mistakes in others to thinking about them in

ourselves.

Think of one example of when you have defended opinions in each of these ways. Socratic wisdom requires us to be wise by

realizing that we are not wise.

4. Socrates, A Martyr for Wisdom

© 2018 SOPHIA Learning, LLC. SOPHIA is a registered trademark of SOPHIA Learning, LLC. Page 22As the previous thought experiment demonstrates, it is easier to recognize the mistakes of others than those we make. It is easier to

say than to do, to "talk the talk" than "walk the walk." One of the most important aspects of Socrates’ legacy is that he lived what he

taught, no matter the cost.

While teaching (and learning) philosophy in Athens, asking “why” questions (he referred to himself as a gadfly), Socrates irritated people,

and it got him into trouble. He was charged with corrupting the youth, and put on trial (this trial will be examined in detail in a subsequent

tutorial). Socrates presented his own defense, but did so in philosophical terms. He refused to use rhetorical tricks like the sophists,

and did not appeal to emotions (e.g., by bringing in crying family members before sentencing). He refused punishment by exile that

would have required an implicit admission of regret for his conduct, and an end of his teaching. Had he accepted exile, he would have

avoided execution.

It's unnecessary to speculate whether he was willing to die for his beliefs, or just believed that he was doomed either way. Later, his

friend Crito provided him with an opportunity to escape from prison before his execution, but Socrates did not take it because he

believed that it would be morally wrong for him to do so.

It may be tempting to reason as Crito did and point out how much good Socrates could have done if he had escaped and resumed

teaching. However, if Socrates had, in opposition to his teachings, escaped, would we be reading about him today? Would he have

inspired Plato to pursue philosophy? Would we revere him for acting in a self-serving way, instead of doing what he believed was right?

We remember and revere Socrates because he was one of the few who lived, and died, according to his beliefs.

In this tutorial, we introduced Socrates, the patriarch of western philosophy, and compared his methodologies to the philosophers

who preceded him. His intellectual offspring, including Plato and Aristotle, were incalculably important to the development of

western civilization. Socrates reinvented philosophy as the discipline that it is today. He taught by example, and lived what he

taught even though it cost him his life.

Source: Bust of Socrates, PD, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Socrates#/media/File:Socrates_Pio-Clementino_Inv314.jpg

TERMS TO KNOW

Epistemology

The branch of philosophy that analyzes and defends concepts of knowledge and the methodologies that attain it

Ethics

The branch of philosophy that analyzes and defends concepts of value and thereby seeks to determine right and wrong

© 2018 SOPHIA Learning, LLC. SOPHIA is a registered trademark of SOPHIA Learning, LLC. Page 23The Socratic Approach

by Sophia Tutorial

Socrates, the father of western philosophy, used different approaches to discover the truth, depending on whether a situation

involved opposing viewpoints, or students who wanted to learn from him. His way of teaching continues to influence the manner in

which philosophy is taught today, because it is a way that leads to understanding.

This tutorial investigates the Socratic approach in three parts:

1. The Character of Socrates

2. Dialectic

3. The Socratic Method

1. The Character of Socrates

Socrates was a man of virtue. He is remembered and revered because he lived according to his principles, which he believed were

correct. His life was guided by what sound reasoning led him to conclude was right. He was a man of keen intellect and upstanding moral

character.

Socrates’ life was completely involved in the pursuit of philosophy, truth, and wisdom. What he did not know, he sought to discover. The

Symposium describes Socrates standing outside a building before entering a party that was being held there, thinking about something

that had been puzzling him. His extreme dedication to learning led him to become a teacher. Although he was an excellent instructor, he

did not charge his students for the lessons they received. He shared wisdom with all who sought it.

Socrates dedicated his life (and death) to doing what he thought was right, to his quest for wisdom and ethics. His final moments are

recorded in a dialogue called the Phaedo, which will be covered in a subsequent tutorial. The last line of the Phaedo summarizes how he

is regarded by those who knew him: “Such was the end…of our friend; concerning whom I may truly say, that of all the men of his time

whom I have known, he was the wisest and justest and best.”

2. Dialectic

Socrates sought wisdom through philosophy. He believed that philosophy was best pursued by a method (carried on by Plato) called

dialectic.

Dialectic

A discourse between two or more people of opposing viewpoints, the goal of which is to discover truth through reasoning

Dialectic is a somewhat more noble endeavor than debate. The goal of a debate is to win — to use arguments in a way that enables your

side to prevail. (The skill used to win debates is rhetoric.) Winning, however, is not the goal of dialectic.

Dialectic is used to find the truth. When opposing viewpoints are involved, one is wrong, and the other is right. It is the dialectician's job

to determine which is which. This is a philosophical endeavor: not only because philosophy pursues truth and seeks to separate

knowledge from opinion, but also because of the importance of logic and reasoning in dialectic.

Unlike the process of rhetorical debate, only good reasoning prevails in philosophical dialectic. Since logic, like mathematics, is

universal and dispassionate, when the truth is discovered, both sides in a dialectic can, should, and do recognize it. Since the emphasis

is on truth and reason, bias, emotion, upbringing and worldview are set aside. This makes dialectic objective process, motivated by a

genuine desire for truth on all sides.

Imagine contemporary political debates being conducted in this way. If two political opponents were united in a search for truth, they

would engage in genuine, open-minded inquiry as to what is the best course of action for their country, instead of the familiar quest for

personal advantage and victory.

If this seems unrealistic, focus on your own experience.

Consider whether you have ever had a discussion, perhaps with a friend or sibling, that resembled a dialectic. What influenced the

way in which this discussion took place? First and foremost, respect. You didn’t assume the worst about the person with whom you

were chatting. You did not immediately dismiss his/her position as wrong. Also, since you did not dismiss his/her position, you

questioned your own view. The discussion was a dialectic because you disagreed respectfully, and it was fruitful because you held

your own view as being subject to questioning, rather than as inviolable. Neither of you tried to prove the other wrong. Together, you

© 2018 SOPHIA Learning, LLC. SOPHIA is a registered trademark of SOPHIA Learning, LLC. Page 24were simply searching what is true.

Socrates conducted all of his inquiries in this way, and did not assume that any of his beliefs were inviolable. When following this

standard, it does not matter whether you respect the person with whom you disagree, or whether you respect his or her point of view.

All that matters is that you respect truth. If you do, you will ensure that all of your beliefs are true (or not) by questioning them. You will

care enough about truth to share it with others.

3. The Socratic Method

Dialectic is used by those who hold opposing viewpoints to dispassionately search for truth. Although the opponents initially disagree,

they do so respectfully. A different method is required when one who knows a truth wants to teach it to others. When teaching, Socrates

used the Socratic Method.

Socratic Method

The pedagogical method of teaching by asking questions to which the student knows the answers, thereby leading them, step by

step, to the truth being taught

Suppose a teacher has taught students how to multiply using flashcards, and is moving on to more complicated multiplication problems.

Example of the Socratic Method

Teacher: Do you know what 8 times 72 is?

Student: No, I don’t.

Teacher: Do you know what 8 times 2 is?

Student: Of course, it’s 16.

Teacher: Do you know what 8 times 3 is?

Student: Of course, it’s 24.

Teacher: And what about 8 times 5?

Student: It’s 40.

Teacher: And 3 plus 2?

Student: 5, of course.

Teacher: And 3 times 8 plus 2 times 8.

Student: …40.

Teacher: So to compute 5 times 8, we can add two numbers that equal 5, eight times, then add their products?

Student: It seems so.

Teacher: Does it work with 1 times 8 and 4 times 8?

Student: Yes!

Teacher: It should always work, since we know that multiplication is a complex form of addition. How might we multiply 72

times 8?

Student: Multiply some numbers that add to 72 by 8 and add their products.

Teacher: And which numbers might be easier?

Student: The ones I know.

Teacher: Good, so you already know 8 times 2.

Student: Yes, 16.

Teacher: What would we have to add to 2 to get 72?

Student: 70.

Teacher: What is 8 times 70?

© 2018 SOPHIA Learning, LLC. SOPHIA is a registered trademark of SOPHIA Learning, LLC. Page 25Student: I don’t know.

Teacher: What is 8 times 7?

Student: 56.

Teacher: So if 70 is seven tens, isn’t 8 times 70, 56 tens?

Student: It must be!

Teacher: So what is 8 times 70?

Student: 560!

Teacher: And what is 8 times 72?

Student: 576!!!

In this example, the teacher has taught the student something new. This new knowledge will be the basis for solving longer

multiplication problems. The teacher demonstrated how new knowledge can be achieved, starting from what the student already knows.

This teaching method has two advantages: Student who have accomplished some basic learning don't need to "reinvent the wheel" when

attempting to answer more difficult questions. They can leverage what they already know.

Additionally (and more importantly, with respect to philosophy, and to life), by beginning with what he or she already knows, and

comprehending why the answer is what it is, students understand that an answer is true. This is the advantage of the Socratic Method. It

is still used in schools, from the elementary through the doctoral level. It is an effective tool for teaching understanding, because it leads

the student to knowledge, instead of dictating it. It shows students how to achieve knowledge on their own, rather than simply giving

them a collection of facts.

Socrates is not only known for his constant quest for wisdom, and his rigorous commitment to right living, but also for his teaching

method. He believed that truth and wisdom should be shared, not hoarded. He used dialectic to discover truth, and the Socratic

Method to help others find it.

Source: Quotation from the Phaedo retrieved from Project Gutenberg: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/1658/1658-h/1658-h.htm

TERMS TO KNOW

Dialectic

A discourse between two or more people of opposing viewpoints, the ultimate goal of which is to discover the truth of the

matter through reasoning

Socratic Method

The pedagogical method of teaching by asking questions to which the student knows the answer and thereby leading them to

the truth being conveyed

© 2018 SOPHIA Learning, LLC. SOPHIA is a registered trademark of SOPHIA Learning, LLC. Page 26Introducing Arguments

by Sophia Tutorial

Philosophy uses argumentation to attain truth. To learn how to evaluate arguments, we must first define argument.

This tutorial examines argumentation and its role in philosophy, in two parts:

1. What is an Argument?

2. The Basics of Evaluation

1. What is an Argument?

In philosophy, arguments provide justification for proposed positions. When successful, an argument provides a reason (or reasons) to

believe that something is true. Aristotle provided the following example of a simple argument:

All men are mortal.

Socrates is a man.

Therefore, Socrates is mortal.

Think of the argument as an equation. The first two statements (both of which are called premises) combine to yield the third (the

conclusion). Hence, if we know the two premises, we also know the conclusion.

Premise

A statement presented in an argument for acceptance or rejection without support, but that is intended to support a conclusion

Conclusion

A statement that is intended to be supported by the premises of an argument

As we will see, the argument above provides justification for thinking that Socrates is mortal. To do so, it must accomplish two things.

Every argument makes both a factual claim and an inferential claim.

Factual Claim

A claim that some fact (or facts) corresponds to reality

Inferential Claim

A claim that the premises support the conclusion

Note that we are currently defining what makes an argument, not what makes a good argument. It is important to understand that claiming

that a fact corresponds to reality does not guarantee that it does (“Socrates was a fire-breathing lizard who ravaged the streets of

Tokyo” is a factual claim), and claiming that premises support a conclusion does not mean that they do. These two claims must be

evaluated to determine the success of an argument, as will be discussed below. An argument is defined as follows:

Argument

A group of statements containing both a factual claim or claims and an inferential claim or claims

An argument must contain both types of claims; and all groups of statements that contain both types of claims are arguments. Regarding

the statements provided above, in order for them to form an argument, they (together) must make a factual claim or claims.

See if you can find the factual claims in Aristotle's argument, above.

Factual claims are submitted as true, but without support. The argument itself (i.e., the three sentences provided above) includes no

reasons to support the claims made in it.

The two factual claims in this argument are “All men are mortal” and “Socrates is a man”. Notice that they are presented as givens with