SEJPME Introduction to Joint Duty PreTest 2023 verified!

$ 7.5

📘 RBT Task List Review – Comprehensive Study Guide

$ 10

Chapter 20: Lipid Metabolism Exam, questions and answers Biochemistry. 100%

$ 6.5

ENGLISH MOCA Test Questions | 100% Correct Answers

$ 5

[eBook] [EPUB] [PDF] Using Artificial Intelligence Absolute Beginner's Guide BY Michael Miller

$ 25

San Francisco State University<CS 1101<Purposive-Communication-Prelim Answer (1REVIEWED AND EDITED BY EXPERTS 2021

$ 13

Sophia Public Speaking Milestone 1, Updated Revision

$ 18.5

Sophia Visual Communications Final Milestone, Questions with Complete Answers

$ 15

CS 573: Algorithms, Fall 2013 Homework 3: Solutions

$ 8

NR 509 Final Exam Study Guide

$ 19.5

WGU Course C170 - Data Management (Applications), Exam Question with accurate answers, 100% Accurat

$ 12

PT_Exam_Sample_Questions_secrets UPDATED 2019

$ 47.5

SEC 571 Week 7 Discussion Question 2: Security Skills

$ 7

AQA GCSE Mathematics Geometry - Common Answers and Commentaries. 2021 Assessment resources

$ 6

Pearson Edexcel International GCSE_Mathematics A_4MA1/1H Question Paper June 2021 | PAPER 1H Higher Tier

$ 7.5

WGU C468 Information Management and the Application of Technology Questions and Answers Rated A+

$ 7

ATI Comprehensive Predictor Study Guide 2021

$ 18

Test Bank For Community Development in Canada, 3rd Edition by Jason D. Brown Chapter 1-11

$ 19

Pearson Edexcel International GCSE In Physics (4PH1) Paper 1P and Science (Double Award) (4SD0) Paper 1P Mark Scheme (Results) January 2022

$ 7

PEARSON EDEXEL A level MARKSCHEME FURTHER MATHS MARKSCHEME | Core Pure Mathematics 2 - June 2023

$ 7

Template for Unit 4 Touchstone - Communication at Work Final

$ 13

Psychological Testing: Principles, Applications, and Issues, 8th Edition, Kaplan & Dennis. All Chapters 1-21 | TEST BANK

$ 19

Grand Canyon University - COM -312COM-312 Negotiation.

$ 7

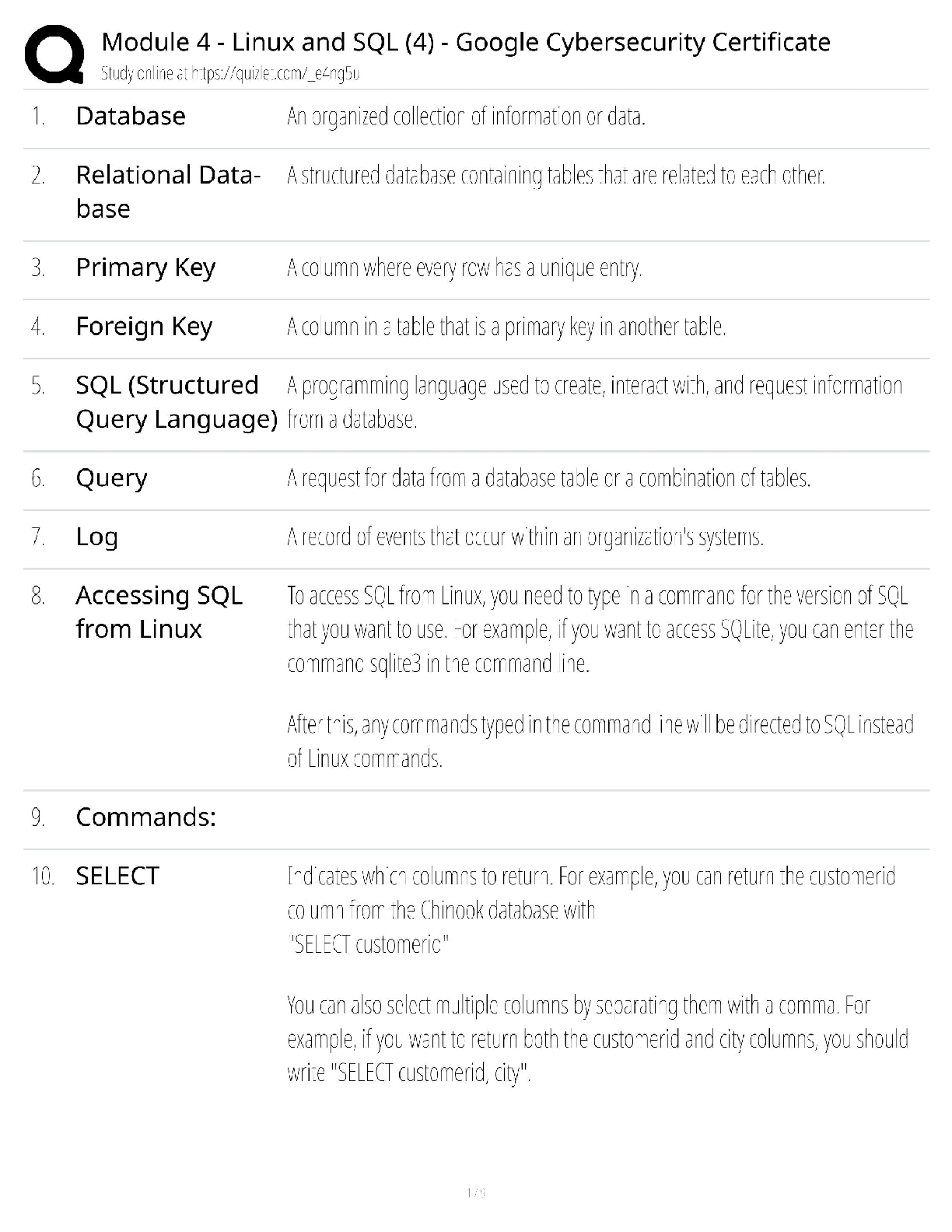

Google Cybersecurity Cert - Module 4 / Linux & SQL Crash Course / 2025 Exam Guide / Hands-On Labs

$ 11

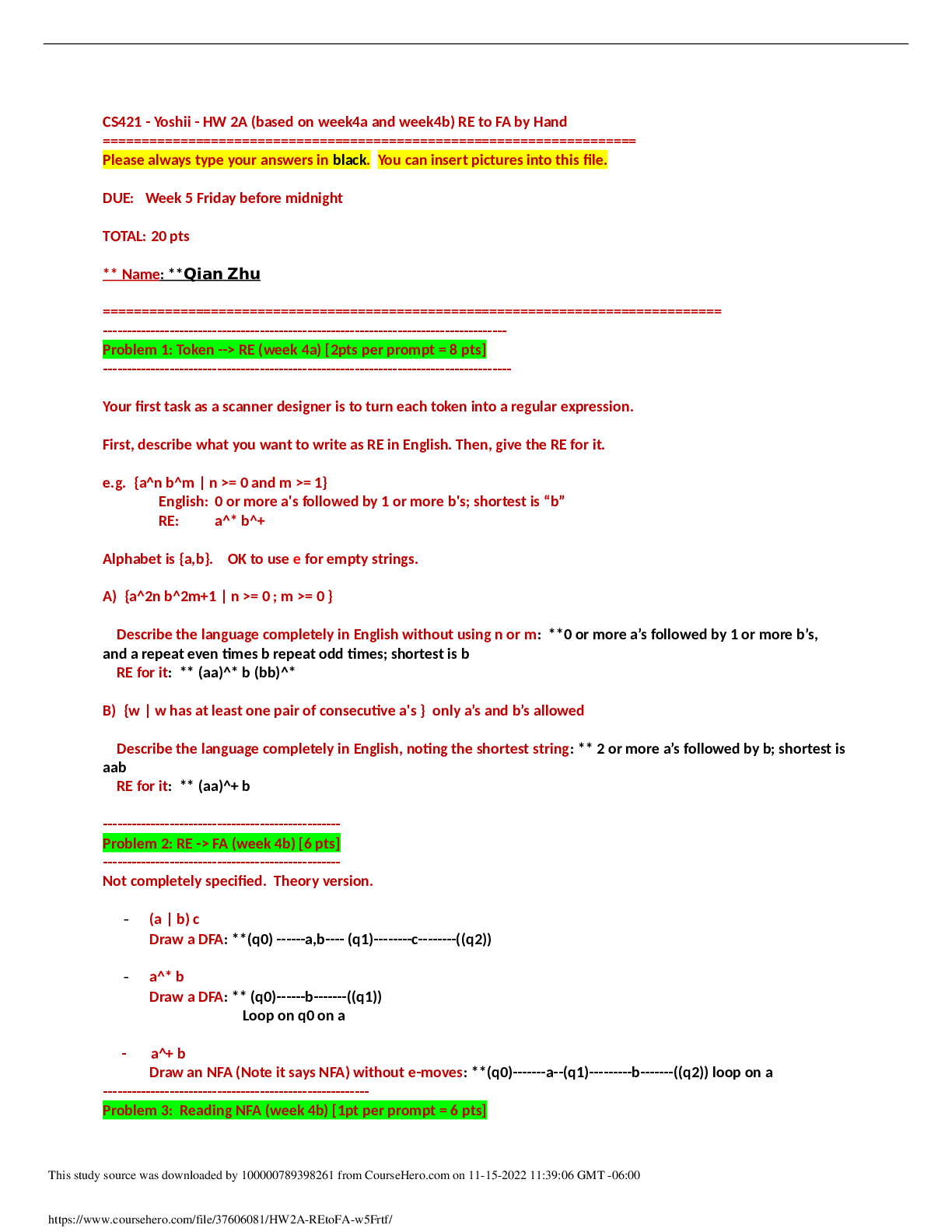

CS 421 Theory of computing CS421 HW 2A (based on week4a and week4b) RE to FA by Hand | California State University, San Marcos

$ 8

Virginia Tech - CS 1114 MazeRunner.java.

$ 8.5

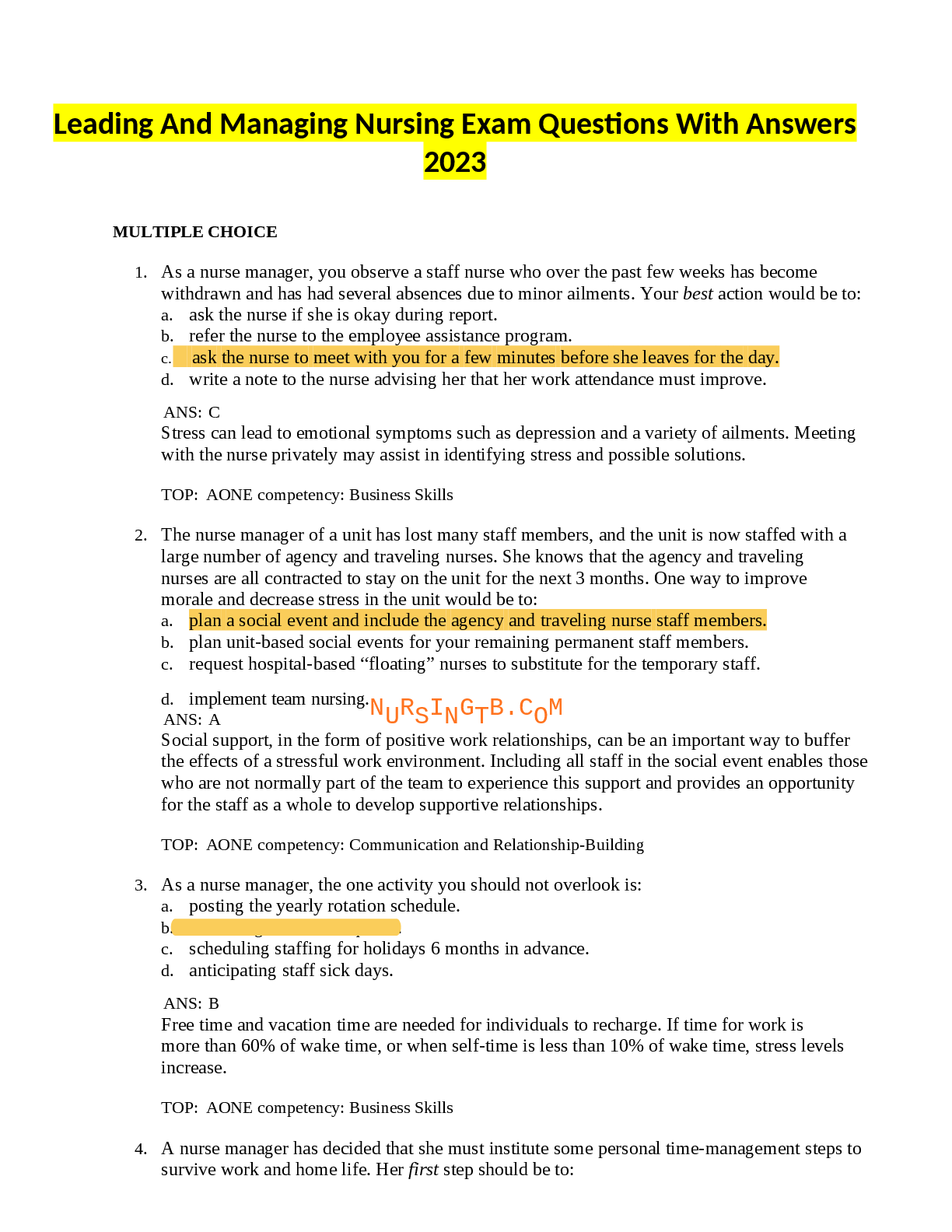

Leadership final pdf 1 .docx

$ 14

Test Bank Econ 212

$ 18

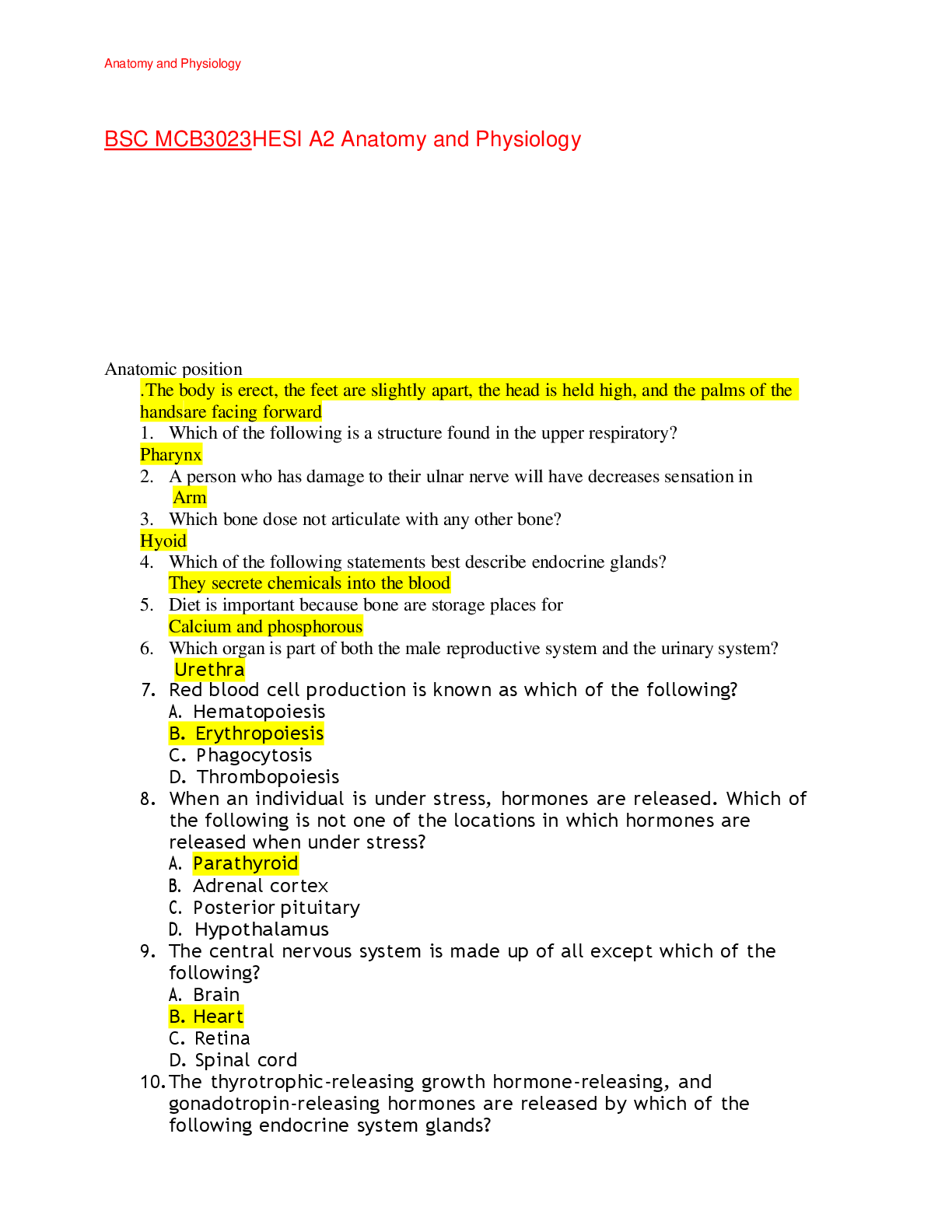

BSC MCB3023 HESI A2 Anatomy and Physiology

$ 18

FINAL EXAM STUDY GUIDE COMPLETE QUESTIONS WITH ANSWERS.png)

NCLEX RN PHARMACOLOGY_ NEUROLOGICAL MEDICATIONS (2020_2021) FINAL EXAM STUDY GUIDE COMPLETE QUESTIONS WITH ANSWERS

$ 23

(WGU D344) NURS 6437 DIAGNOSTIC PROCESS OF PSYCHIATRIC NURSE COMPREHENSIVE FINAL OA GUIDE 2024

$ 12

eBook [PDF] Green Chemistry in Food Analysis By Shahid Ul Islam, Chaudhery Mustansar Hussain

$ 33

Pearson Edexcel International GCSE_Mathematics A_4MA1/2H Mark Scheme Jan 2021 | Paper 2H

$ 7.5

ABS 302: Ethical & Policy Issues in BioTestQuiz 2 | Download for quality grades|

$ 25

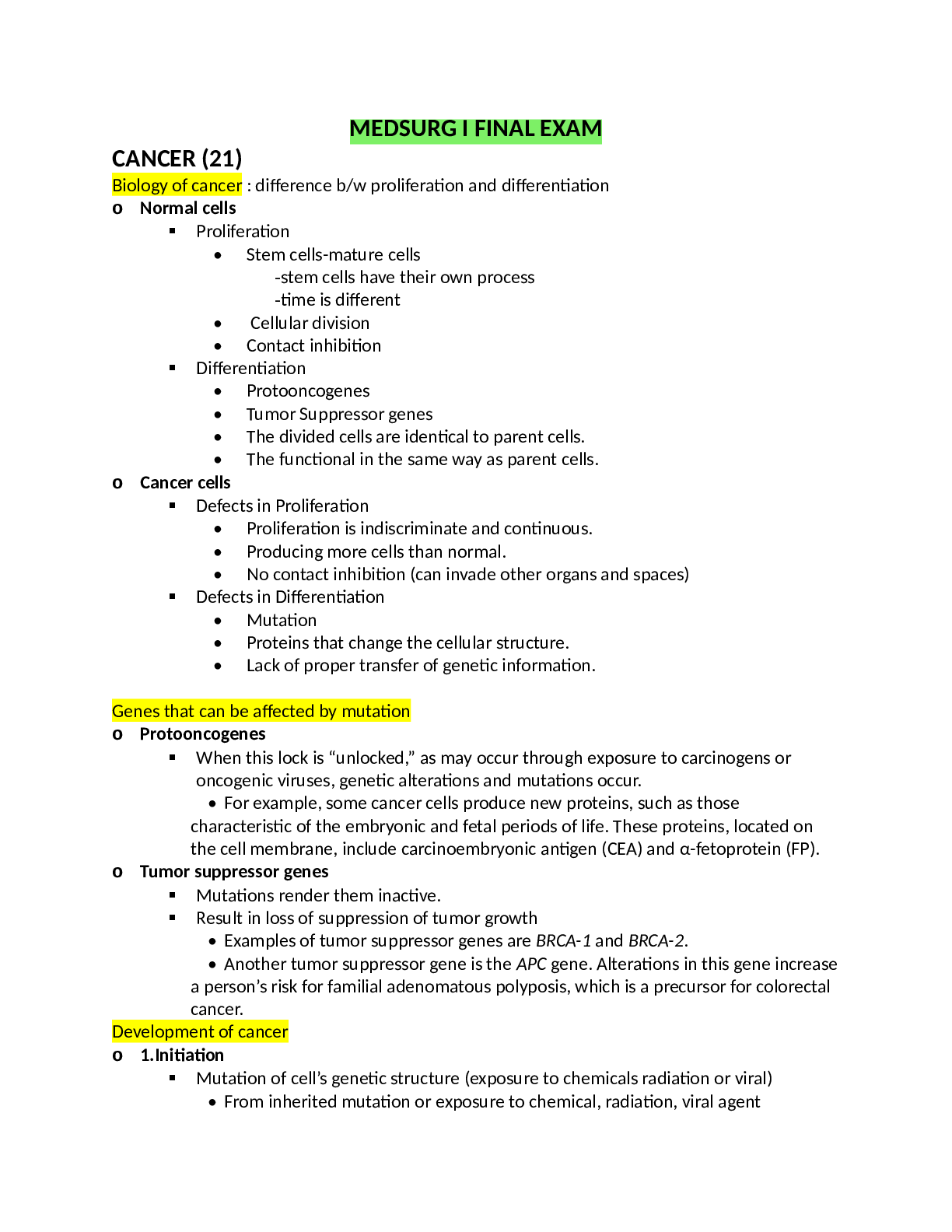

NUR 232 ATI MED SURG 1 FINAL EXAM Study Guide 2020/2021

$ 25

Chapter 11 Homework

$ 20

Hesi Passage and Highlight

$ 7

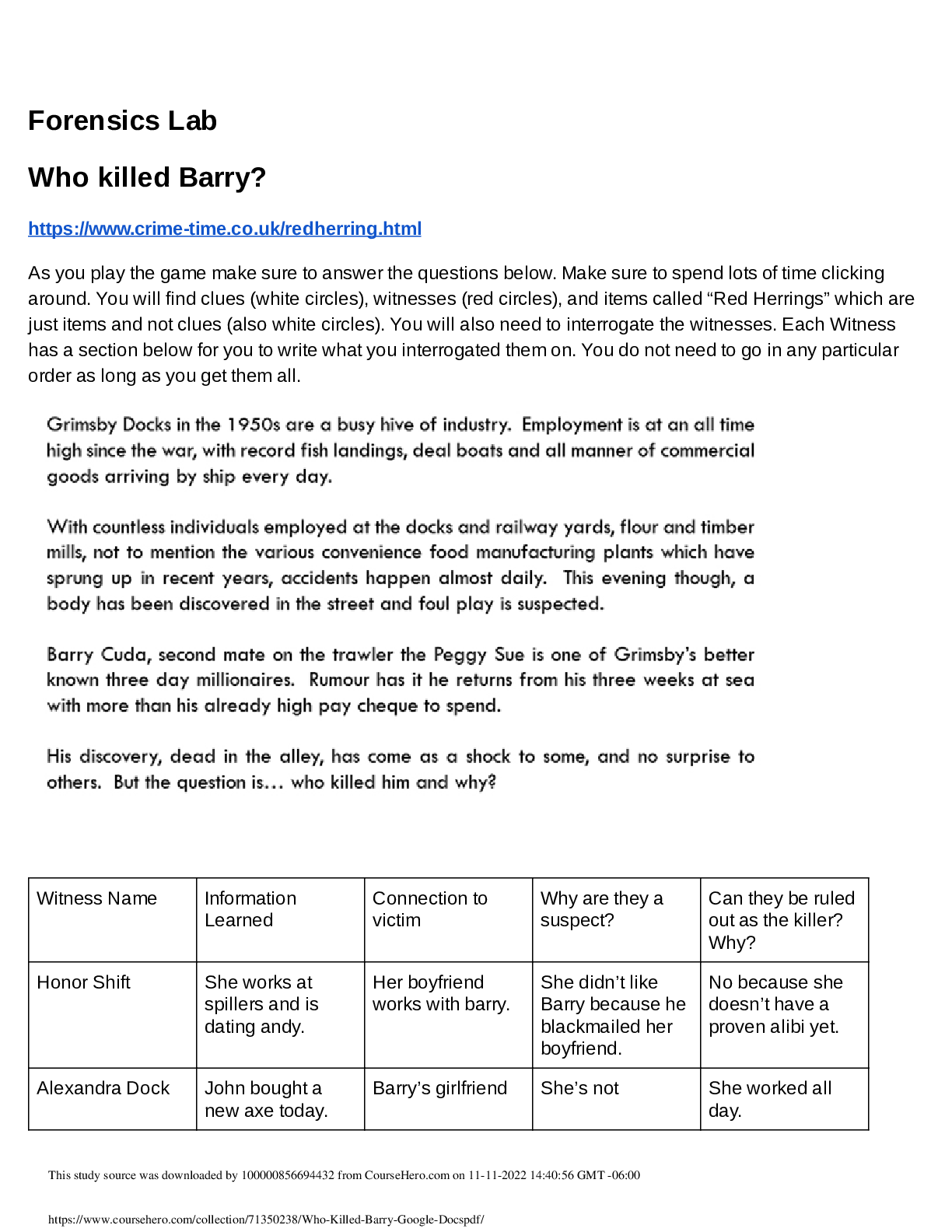

Forensics Lab Who killed Barry?

$ 7

Strayer University - CIS 348 Post Assessment Questions And Answers (Latest )

$ 13

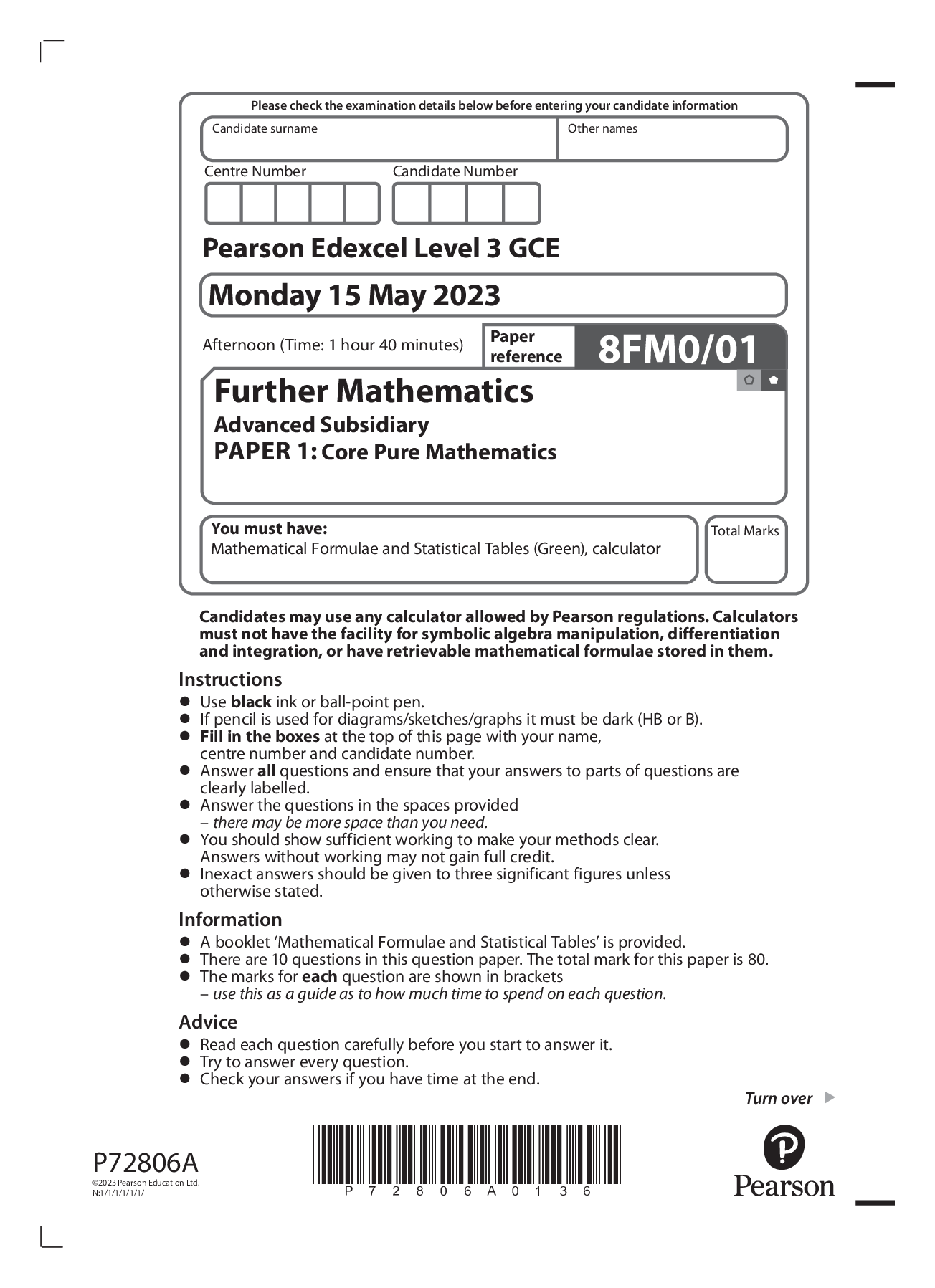

PEARSON EDEXCEL AS LEVEL FURTHER MATHS PAPER 1: Core Pure Mathematics June 2023 | QUESTION PAPER

$ 7

Test Bank For American Government and Politics Today Brief 12th Edition By Steffen Schmidt, Mack Shelley, Barbara Bardes, Brian King

$ 30

Kaleys Comprehensive Study Guide final BIOCHEM C785

$ 20

Final Exam_MATH302_AMERICAN_UNIVERSITY_UPDATED_SUMMER_2021_EXAM_10_PAGES

$ 14

CMIS 342 Exam SIUE | Questions with 100% Correct Answers

$ 14.5

Pearson Edexcel International GCSE Mathematics A (4MA1) Paper 1HR Mark Scheme (Results) January 2021

$ 6

APEA_3P_Exam_Pre5

$ 9.5

UNIT_32_OIL_HEAT_EXAM_QUESTIONS_AND_ANSWERS_VERIFIED_LATEST_UPDATE

$ 15

Stony Brook University PHY 134 efield plot Breadboard Lab

$ 8

BSC MCB3023: HESI A2 REVIEW WITH VERIFIED AND QUALITY ANSWERS ,vsu

$ 30

Creating a GUI Bank Balance Application CSC 372 Colorado State University – Global Campus

$ 6.5

ATI Medical Surgical Nursing, Assessment of the Endocrine System, 2021 Update Study Guide, Correctly Answered Questions, All Correct Test bank Questions and Answers with Explanations (latest Update), 100% Correct, Download to Score A

.png)