*NURSING > STUDY GUIDE > NR 601 Midterm Exam review Study Guide_Latest,100% CORRECT (All)

NR 601 Midterm Exam review Study Guide_Latest,100% CORRECT

Document Content and Description Below

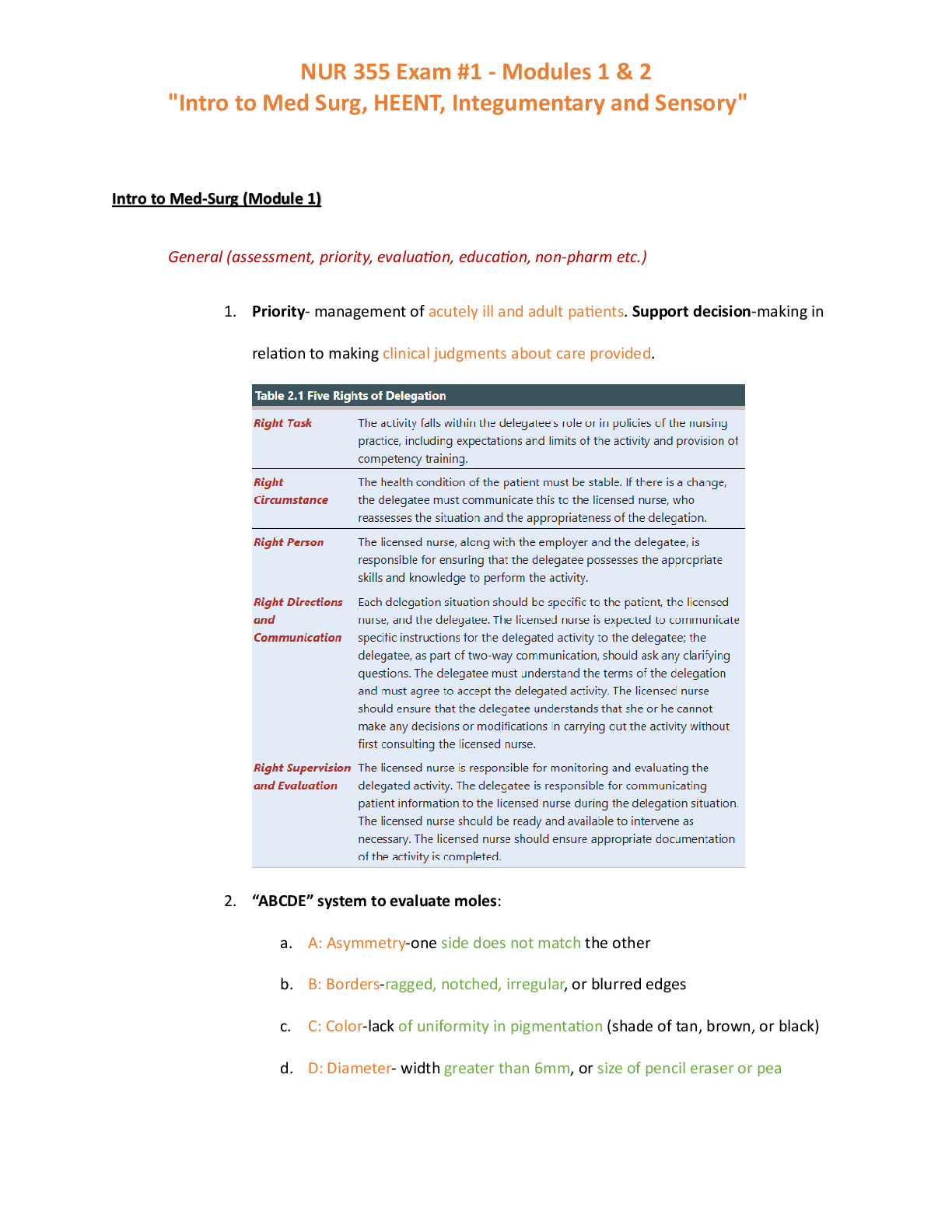

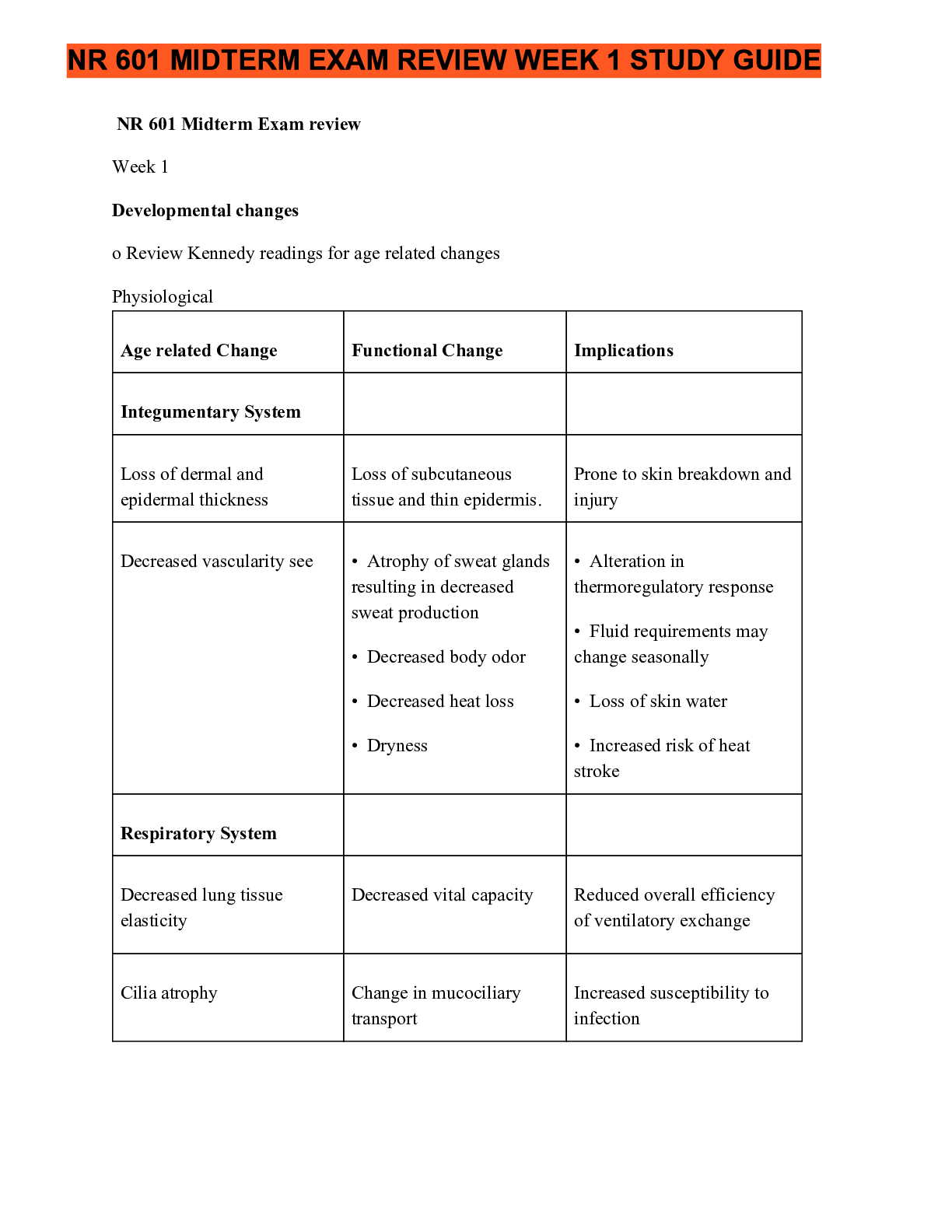

Developmental changes o Review Kennedy readings for age related changes Physiological Decreased respiratory muscle strength • Reduced ability to handle secretions and reduced effectivenes ... s against noxious foreign particles Increased risk of atelectasis • Partial inflation of lungs at rest Cardiovascular System Heart valves thicken and become fibrotic Reduced stroke volume, cardiac output; may be altered Decreased responsiveness to stress Fibroelastic thickening of Slower heart rate Increased prevalence of the sinoatrial node; arrhythmias decreased number of pacemaker cells Decreased baroreceptor sensitivity (stretch receptors) Decreased sensitivity to changes in blood pressure Prone to loss of balance, which increases the risk for falls GI Liver becomes smaller Decreased storage capacity Decreased muscle tone Altered motility Increases risk of constipation, functional bowel syndrome, esophageal spasm, diverticular disease Decreased basal metabolic rate (rate at which fuel is converted into energy) May need fewer calories o Lab results (JACKELINE CONDE) Lab results Hematocrit Men: 45-52% Women 37-48% Slight decreased speculated Decline in hematopoiesisLeu Leukocytes 4,300–10,800/mm3 Drop to 3,100–9,000/mm3 Decrease may be due to drugs or sepsis and should not be attributed immediately to age Lymphocytes 00–2,400 T cells/mm3 50–200 B cells/mm3 T-cell and B-cell levels fall Infection risk higher; immunization encouraged Platelet 150,000–350,000/ No change in number Blood Chemistry Albumin 3.5–5.0 Decline Related to decrease in liver size and enzymes; protein-energy malnutrition common Globulin 2.3–3.5 Slight increase Total serum protein 6.0–8.4 g No change Decreases may indicate malnutrition, infection, liver disease Blood urea nitrogen Men: 10–25 Women: 8–20 mg Increases significantly up to 69 mg Increases significantly up to 69 mg Creatinine 0.6–1.5 mg Increases to 1.9 mg Related to lean body mass decrease Creatinine clearance 104–124 mL/min Decreases 10%/decade after age 40 years Used for prescribing medications for drugs excreted by kidney Glucose tolerance 62–110 mg/dL after fasting; >120 mg/dL after 2 hours postprandial Slight increase of 10 mg/dL/decade after 30 years of age Diabetes increasingly prevalent; drugs may cause glucose intolerance Alkaline phosphatase 13–39 IU/L Increase by 8–10 IU/L Elevations >20% usually due to disease; elevations may be found with bone abnormalities, drugs (e.g., narcotics), and eating a fatty meal o Atypical disease presentations 1. Acute abdomen Absence of symptoms or vague symptoms, acute confusion, mild discomfort and constipation, some tachypnea and possibly vague respiratory symptoms, appendicitis pain may begin in right lower quadrant and become diffuse 2. Depression Anorexia, vague abdominal complaints, new onset of constipation, insomnia hyperactivity, lack of sadness 3. Hyperthyroidism Hyperthyroidism presenting as “apathetic thyrotoxicosis,” i.e., fatigue and weakness; weight loss may result instead of weight gain; patients report palpitations, tachycardia, new onset of atrial fibrillation, and heart failure may occur with undiagnosed hyperthyroidism 4. Hypothyroidism Hypothyroidism often presents with confusion and agitation; new onset of anorexia, weight loss, and arthralgias may occur 5. Malignancy New or worsening back pain secondary to metastases from slow growing breast masses Silent masses of the bowel 6. Myocardial Absence of chest pain infarction (MI), vague symptoms of fatigue, nausea, and a decrease in functional and cognitive status; classic presentations: dyspnea, epigastric discomfort, weakness, vomiting; history of previous cardiac failure, higher prevalence in females versus males Non-Q-wave MI 7. Overall infectious diseases process Absence of fever or low-grade fever, malaise 8. Sepsis Without usual leukocytosis and fever, falls, anorexia, new onset of confusion and/or alteration in change in mental status, decrease in usual functional status 9. Peptic ulcer disease Absence of abdominal pain, dyspepsia, early satiety, painless, bloodless, new onset of confusion, unexplained, tachycardia, and/or hypotension 10. Pneumonia Absence of fever; mild coughing without copious sputum, especially in dehydrated patients; tachycardia and tachypnea; anorexia and malaise are common; alteration in cognition. 11. Pulmonary edema Lack of paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea or coughing; insidious onset with changes in function, food or fluid intake, or confusion 12. Tuberculosis (TB) Atypical signs of TB in older adults include hepatosplenomegaly, abnormalities in liver function tests, and anemia 13. Urinary tract infection Absence of fever, worsening mental or functional status, dizziness, anorexia, fatigue, weakness o Geriatric syndromes refers to conditions that involve multiple organ systems. Most common are delirium, falls, dizziness and incontinence. risk factors include: older age, cognitive impairment, functional impairment,and impaired mobility. Bowel incontinence- involuntary passage of stool or the inability to control stool from expulsion. More prevalent in women than men. 3 types: urge incontinence, passive incontinence, and fecal seepage. urge- has desire to go but cannot make it to the toilet despite attempts to avoid defecating. Passive-involuntary loss of gas and stool without awareness. fecal seepage- leakage of stool after a normal bowel movement. etiology : a number of reasons including GI issues, cognitive or neurological diseases. Treatment: treat related etiology such as impaction of increasing fiber. Habit training is also recommended. Once clear evidence of no impaction, infection, or cause is determined. antidiarrheal medication like Imodium can be tried. For retrosphincter dysfunction biofeedback with strengthening exercises for the sphincter can be done. Constipation: presence of 2 or more symptoms: decreased stool frequency, straining, hard stools, sensation of incomplete emptying, blockage at anorectal site. constipation is most common digestive complaint. Cough: forceful expelling of air from the lungs involving the use of accessory muscles of the chest and constriction of the glottis. dehydration:caused by too little fluid intake, too much fluid lost or both. Chronic diseases like diabetes, cancer, cardiovascular diseases, and renal diseases make elderly sensitive to fluid shifts. Diarrhea: Passage of increased stool frequency, liquidity, or volume. Most episodes are caused by viral gastroenteritis. Chronic diarrhea is defined as lasting longer than 4 weeks. Dizziness: common clinical categories include vertigo, light-headedness, unsteadiness, or gait instability, and disequilibrium. Falls: WHO defines this as an event that results in a person coming to rest inadvertently on the ground, floor, or other lower level. can be witnessed or unwitnessed. due to intrinsic factors or extrinsic factors. Intrinsic factors include age, weakness, gait/balance, poor vision and postural hypotension. Extrinsic factors involve environment conditions like lack of handrails, poor lighting, obstacles, slippery surfaces, certain medication, and polypharmacy. Fatigue ● Description ○ Subjective state often described as a feeling of tiredness, weariness, lack of energy, or exhaustion that is unrelieved or only partially relieved by rest ○ Often results in an inability to initiate normal activity; a reduced capacity to maintain activity; and difficulty with concentration, memory, and emotional stability ○ Chronic fatigue syndrome occurs when fatigue lasts longer than 6 months and is not relieved with rest ○ Fatigue could also be a symptom of another illness and any older person with this complaint should obtain a medical evaluation and work-up. ● Etiology ○ Occurs normally with inadequate rest, excess exertion, or insufficient diet ○ Fatigue in older adults may be an early indicator of the aging process, as well as debility or another disorder ● Occurrence ○ 25% of the US population ● Age ○ Common among the elderly ● Gender ○ More common in women ● Ethnicity ○ Not significant ● Contributing Factors ○ Poor dietary habits, overexertion, alcohol abuse, smoking, stress, chronic illness, drug interactions, misuse of drugs, and sleep apnea ○ In the older adult individual, it is compounded by a decrease in muscle strength, loss of muscle neurons, muscle atrophy, a decrease in hormone levels, and lack of exercise. ● Signs and symptoms ○ Conduct a complete symptom assessment, including the onset; duration; severity; and precipitating, aggravating, and relieving factors. ○ Identify other indicators or associated symptoms of fatigue, which may include decreased energy expenditure, decreased endurance, sleep disturbance, attention deficits, somatic complaints (aching body, tired eyes), dyspnea, and weakness ○ Carefully review the adequacy of the diet, all medications (evaluating for potential medication side effects), activity level (including degree of independence of ADLs), and potential causes or contributing factors. Identify the impact fatigue is having on the person’s ADLs and quality of life and current stressors. ○ Distinguish between generalized fatigue and actual weakness by testing for muscle strength and presence of localized tenderness ○ A thorough physical examination will include a mental status examination to screen for dementia and rule out depression. ● Diagnostic tests ○ Diagnostic tests on all patients with persistent unresolved fatigue should include CMP, CBC with differential, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and/or C-reactive protein, because these are low cost and offer significant screening capacity. ○ Thyroid function, urinalysis, and pulmonary function tests. ○ If symptoms and signs indicate cardiac decompensation, a B-type natriuretic peptide (BNP) may indicate degree of heart failure and an EKG may reveal cardiac arrhythmias, enlargement of the heart, myocardial infarction, or abnormalities in the conduction system ● Differential diagnosis ○ Psychiatric disorders, including depression and generalized anxiety disorder, account for 70% of cases of fatigue ○ Fatigue that cannot be relieved by rest or sleep is often a sign of disease. ● Treatment ○ Symptom management includes regular exercise, attention-restoring activities, psychosocial techniques, energy conservation measures, good sleep hygiene, improving diet, and possibly adding nutritional supplements ○ Psychostimulants may be considered for opioid-related somnolence, cognitive impairment, and depression ● Follow up ○ Monitor the patient periodically as indicated by diagnosis or symptoms, symptom persistence, and disability associated with the symptom ● Sequelae ○ The potential for complications relates to the cause of fatigue and the impact the symptom has on the person’s function ● Prevention/Prophylaxis ○ Optimal health maintenance, including maintaining a healthy diet, regular exercise, and good sleep hygiene, may prevent or enable early recognition of signs and symptoms of systemic or psychological illness ● Referral ○ May be indicated based on the results of the work-up ● Education ○ If the fatigue has a physiological cause, teaching should be related to the findings; psychological counseling, changes in the environment, behavior modification, and stress reduction may be needed Goal of fatigue management - provide the patient with self-help tools to eliminate or alleviate fatigue Headache: Hematuria: Description: Presence of RBCs in the urine, classified either gross or microscopic Gross hematuria: urine appears either red or brown in color to the naked eye Microscopic hematuria: identified by lab analysis. Significant if 3 or more RBCs per high-power field on accurately collected urine specimen. *requires evaluation, 5% with microscopic hematuria are found to have malignancy, & 30-40% with gross hematuria are have to have malignancy Etiology: renal or contamination from outside the urinary tract. Renal hematuria may result from glomerular or nonglomerular causes.Source of hematuria may be the upper collection system (renal, ureter) and/or lower collection system (bladder, prostate, urethra). Common finding on routine UA and etiologies range from life-threatening to benign incidentals. Patho depends on the anatomica site from which blood loss occurred, older adults, most common causes are malignancy or BPH Occurrence: prevalence of asymptomatic microscopic hematuria ranges form 2% to 31% in the adult population, older than 50 yrs., prevalence 13% Age: increases with age, younger pts are less likely to have an etiology identified Ethnicity: not significant Contributing factors: infection, anticoagulation, renal calculi, trauma, anatomical defects such as rectocele, menstruation, atrophic vaginitis, renal disease, or recent urological procedure, malignancy include age more than 35 yrs. male sex, current or past history of smoking, occupational exposures to chemicals or dyes, hx of gross hematuria, chronic cystitis,pelvic irradiation, exposures to cytotoxic agents S/Sxs: thorough HX, presence of visible blood in the urine, Hx of vigorous exercise, recent prostate examination or procedure, recent trauma to the abdomen, recent catherterization, menstruation, renal disease, viral illness, medications (analgesics, antibiotocs, anticoagulants, NSAIDS). Symp represents kidney disease or stone. urinary frequency, lower abdominal pain or dysuria, which may indicate UTI. PE: focus on abdominal/flank pain, urogenital examination, prostate, testicular and vaginal examination Dx Tests: UA with microscopy. Urine dipstick evaluation may be misleading because it lacks the ability to distinguish RBCs from myoglobin or HgB, should confirm with heme-positive dipstick with a microscopic UA. CMP for metabolic abnormalities, elevated creatinine: indicates acute or chronic renal disease and should be referred to nephrologist. PT/INR if on anticougulation and CBC. Multiphasic CT urography or IV pyelogram if suspiciuos of kidney stone, renal mass or malignancy. Cystoscopy for patients 35 years of age, pts younger than 35 yrs if no other reason for hematuria is present, pts of any age if with risks factors for CA., dx bladder or prostatic CA DDX: infection or supratherapeutic anticoagualton should be r/o as reversible causes of hematuria. serious causes: glomerular disease, renal calculi, trauma, anatomical defects, or malignancy TX; directed at the cause, asymptomatic (isolated) does not require treatment. Appropriate ABT therapy for UTI should resolve the hematuria, anticougulation is the cause, adjustment may resolve the problem, kidney stone, initial tx may be pain management and oral hydration. Urosepsis, AKI, anuria, unrelenting N/V should be referred immediately FF-up: repeat UA should be obtained 6 weeks after initial tx for any infection, vigorous exercise, or trauma to make sure that the hematuria has cleared. Refer to urology for gross or microscopic hematuria. Persistent hematuria w/ initial (-) urological ork-up, a repeat UA shold be done yearly and a full repeat evaluation very 3-5 yrs for ongoing hematuria. Referral to nephro if hematuria persists with renal impairment Sequelae: fairly common in young adults under 35 yrs. It could be a sign of malignancy, should not be ignored, even if it is transient. May indicate renal disease, when proteinuria is present, referral to nephro for 2nd opinion. Prevention/Prophylaxis: USPSTF does not endorse routine screening for asymptomatic hematuria due to lack of evidence Refrral : Primary care providers can initiate testing to verify presence of hematuria and treat hematuria if Dx is clear. Referral to nephro is indicated for the presence of proteinuria, RBC casts, dysmorphic RBCs, or elevated serum creatinine level. Referral to urology: hematuria persisting after treatment for a UTI, taking antocoagulants, or in the absence of benign cause, gross and microscopic hemturia Education: Counsel family and patients to seek medical advice about gross hematuria, plus s/sxs to report such as urinary frequency, dysuria, flank and abdominal pain. Educate pts and families abt the SEs of OTC drugs and RX meds, effects of anticoagulant therapy and to call immediately if the pt. notices any hematuria because this may mean the pt’s drug level is too high. Involuntary weight loss: Joint pain: priutis: Tremor: Urinary incontinence: o Exercise in Older adults (Exercise recommendations for specific diagnoses- Kennedy) Osteoarthritis Walking, aquatic activities, tai chi, resistance exercises, cycling Vary type and intensity to avoid overstressing joints; heated pool Coronary artery disease Walking, treadmill walking, cycle ergometry Supervised program with BP and heart rate monitoring Congestive heart failure Walking, treadmill walking, cycle ergometry Individualize to client; supervised program Type 2 diabetes mellitus Resistive, aerobic, aquatic, recreational activities Proper shoe fit; may need insulin reduction if insulin dependent Anxiety disorders Walking, biking, weight lifting If able to do high-intensity exercise, this benefits anxiety Depression Walking, cycling, recreational activities Group participation helpful to keep patient engaged Fibromyalgia Aerobic, aquatic therapy, strengthening, tai chi, Pilates Heated pool, gentle stretches, counsel about possible increased pain initially Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease Cycle ergometer and treadmill walking; individualize Supervised program—consider pulmonary rehabilitation program Chronic venous insufficiency Walking, standing exercises Supervised program Osteoporosis Weight-bearing exercises, weight training Assess balance and risk for falls before beginning Parkinson’s disease Walking, treadmill walking, stationary bike, dancing, tai chi, Pilates, boxing Assess balance and risk for falls before beginning; American Parkinson’s Disease Association resources Peripheral arterial disease Lower extremity exercises, treadmill walking, walking Very short intervals initially, progress as tolerated Age-related sleep disorders Tai chi, walking, aquatherapy, biking Assess balance and risk for falls before beginning Dementia Walking, recreational activities Provide safe environment, assess fall risk and ability to participate (Kennedy-Malone, 20181030, p. 21) o Testing prior to exercise initiation o Barriers, facilitators and contraindications Barriers ■ Lack of time ■ Perceived need for equipment ■ Perceived barrier to beginning exercise/physical activity ■ Disability or functional limitation ■ Unsafe neighborhood or weather conditions ■ No parks or walking trails ■ Depression ■ High body mass index (BMI) ■ Lack of motivation ■ Interpersonal loss or significant life event ■ Ignorance of what to do Patient Facilitators ■ Social support ■ Positive self-efficacy ■ Motivation to engage in physical activity ■ Good health, no functional limitations ■ Frequent contact with prescriber ■ Regular schedule, planned program ■ Satisfaction with program ■ Insurance incentive ■ Improvement in mobility or health condition ■ Staff Contraindications ■ Unstable angina ■ Uncompensated heart failure ■ Severe anemia ■ Uncontrolled blood glucose ■ Unstable aortic aneurysm ■ Uncontrolled hypertension or tachycardia ■ Severe dehydration or heat stroke ■ Low oxygen saturation Health promotion o Immunizations Influenza vaccine is now recommended annually for all adults over 50 years old, unless contraindicated (Table 2-1). Residents of long-term care facilities that house persons with chronic medical conditions are at especially high risk for developing the disease. Health-care workers also should receive the vaccine, preferably before the end of October (Resnick, 2018). Patients with a severe egg allergy or severe reaction to the influenza vaccine in the past and patients with a prior history of Guillain-Barré syndrome should talk with their health-care provider before getting the vaccine. Tetanus-diphtheria toxoids with acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine is administered as a once-in-a-lifetime booster to every adult. Following this, a tetanus-diphtheria (Td) booster is recommended every 10 years. Pneumococcal vaccine is recommended as follows: Administer a one-time dose to PCV13-naïve adults at age 65 years, followed by a dose of PPSV23 12 months later. Hepatitis B vaccine is recommended for high-risk persons such as IV drug users, persons who are sexually active with multiple partners, those living with someone with chronic hepatitis B, patients less than 60 years old with diabetes, and all desiring protection from hepatitis B. The initial dose is given, followed 1 month later by the second dose, then the third dose is given 4 to 6 months after the second dose. Shingrix is a new vaccine for zoster and is recommended over Zostavax. It is administered in two doses. The second dose can be given from 2 to 6 months after the initial one. Persons who have had Zostavax should now be immunized with Shingrix (Resnick, 2018). Those who have had a prior episode of zoster should be vaccinated (CDC, Adult Immunization Schedule, 2017; www.immunize.org). o Recommended health screenings- age ranges and frequency Travel o Risks related to travel: Patients with chronic disease that is well managed at home may decompensate in foreign environments because of heat, humidity, altitude, fatigue, changes in diet, and exposure to infectious diseases.Fever is not always a reliable indicator of illness in the older adult. Seroconversion rates decrease with age, rendering some vaccines less effective for older travelers o Immunizations for travel: all immunizations should be current. influenza, pneumococcal, Td/Tdap (tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis), zoster, and for some, hepatitis B vaccination. Yellow fever and herpes zoster vaccine are the only live virus vaccines that people over age 50 receive. Immune response can be impaired if live virus vaccines are given within a 28- to 30-day interval of each other. Yellow fever vaccine is not effective until 10 days after administration. If the NP gives a patient a herpes zoster vaccine, that patient cannot receive a yellow fever vaccine for 30 days. If the patient is required to have a yellow fever vaccine for travel, he or she cannot enter a yellow fever country until 10 days after receiving the yellow fever vaccine. If a patient receives a yellow fever vaccine, he or she cannot receive a herpes zoster vaccine for 28 days. The patient may receive both vaccines on the same day with no decrease in immune response The most common vaccines used for protecting travelers are hepatitis A, hepatitis B, typhoid fever, yellow fever, adult booster polio, Japanese encephalitis, meningococcal, and rabies. Comprehensive Geriatric Assessment DOMAINS OF COMPREHENSIVE GERIATRIC ASSESSMENT Physical health chief complaint, history of present illness, past history, family and social history, and a review of systems), DIMENSIONS OF COMPREHENSIVE GERIATRIC ASSESSMENT History taking Physical examination Diagnostics Nutritional assessment Medication review Functional health the Katz Activities of Daily Living Scale Activities of daily living Instrumental activities of daily living Sensory assessment (hearing, vision) Gait and balance Psychological health MMSE: the Mini-Cog, Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), and Saint Louis University Mental Status Examination (SLUMS) Cognitive disorders (delirium, dementia, mild cognitive impairment) Affective disorders (depression, anxiety) Spiritual well-being Socioenvironmental Social network and support Supports Lubben Social Network Scale Living situation Environmental safety Economic resources Quality of life measures The Medical Outcomes Study—Short-Form 36 Physical conditions Social conditions Environmental conditions Personal resources (mental health, life perspective) Preferences for care Beers Criteria o Guide to use for medical management of geriatric patient’s o List of potentially inappropriate medications for the elderly-listed by drug category and diagnosis o Lists alternative drugs that can be used safely in older adults o Drug to drug interactions listed, dosage for kidney impairment graded as high, medium, or low to assist with decision making. Polypharmacy o Multiple definitions (review discussion) ● Polypharmacy o Prescribing many drugs, prescribing 5 or more drugs, or prescribing potentially inappropriate medications. o The use of multiple pharmacies (providers & self-prescribers) o Providers should routinely evaluate medication appropriateness to avoid the risk of polypharmacy o Have new patients bring in all medications to their first visit o Review med list at every visit Week 2 COPD o Ask if any other provider has changed or added any meds o Update med list at every visit o Three available tools to evaluate patient’s prescriptions ▪ STOPP (screening tool of older persons’ potentially inappropriate prescriptions ▪ MAI (Medication Appropriateness Index) ▪ ARMOR (Assess, Review, Minimize, Optimize, Reassess) o Signs and symptoms : Dyspnea, chronic cough with or without sputum production, decreased activity tolerance, wheezing.dyspnea, chronic cough with or without sputum production, recurrent lower respiratory infections, wheezing, chest tightness, fatigue, weight loss, and/or anorexia. increased anteroposterior diameter of the thorax, use of accessory muscles for respiration, prolonged expiration, hyperresonance on percussion, decreased heart and breath sounds, tachypnea, neck vein distention during expiration in absence of heart failure, ruddy or cyanotic skin color, and clubbing of nail beds o Diagnostic criteria FEV1/FVC ratio (<70%) ■ Stage 1: Very mild COPD with a FEV1 about 80 percent or more of normal. ■ Stage 2: Moderate COPD with a FEV1 between 50 and 80 percent of normal. ■ Stage 3: Severe emphysema with FEV1 between 30 and 50 percent of normal. ■ Stage 4: Very severe COPD with a lower FEV1 than Stage 3, or those with Stage 3 FEV1 and low blood oxygen levels Asthma o Signs and symptoms Recurrent wheezing, cough (especially at night), recurrent chest tightness, shortness of breath (Kennedy-Malone, p. 155). o Diagnostic criteria FEV 1 /FVC ratio before and after bronchodilator challenge, showing an improvement of 12% and 200 mL, indicates reversible airway obstruction; If spirometry is near normal, bronchoprovocation such as a methacholine challenge test may help to differentiate other conditions with a similar presentation (Kennedy-Malone, p. 155). o Severity classifications (Kennedy-Malone, p. 156) Intermittent: < 2 days/w ; nighttime awakenings: ≤2x/month Persistent Mild: 2 days/week but not daily; nighttime awakenings: 3–4x/month Moderate: daily; nighttime awakenings: 1x/week but not nightly Severe: Throughout the day; nighttime awakenings: often 7x/week Interstitial Lung Disease ILD comprises a heterogeneous group of diseases that cause inflammation and fibrosis of the lower respiratory tract. Four infections may be associated with the cause or onset of most of the various diseases: Ø disseminated fungus (coccidioidomycosis, blastomycosis, histoplasmosis), Ø disseminated mycobacteria Ø Pneumocystis pneumonia, Ø and certain viruses. The largest group comprises Ø occupational and environmental inhalant diseases; these include diseases resulting from inhalation of inorganic dusts, organic dusts, gases, fumes, vapors, and aerosols. Ø Other categories include ILDs caused by drugs, irradiation, poisons, neoplasia, and chronic cardiac failure. Ø unknown causes are idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) and connective tissue (collagen vascular) disorders with ILD, including rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic polymyositis-dermatomyositis, and Sjögren’s syndrome. Seven major entities that are most frequently associated with diffuse ILD are (1) IPF, (2) bronchiolitis obliterans organizing pneumonia, (3) connective tissue (collagen vascular) diseases (SLE, RA, progressive systemic sclerosis [scleroderma], and polymyositis-dermatomyositis), (4) systemic granulomatous vasculitides (Wegener’s granulomatosis, lymphomatoid granulomatosis, and allergic angiitis and granulomatosis), (5) drug-induced pulmonary disease, (6) sarcoidosis, and (7) hypersensitivity pneumonitis. (These entities are briefly discussed further in Box 31.4.Page :416 Dunphy) The first symptom of ILD is usually progressive dyspnea on exertion or a nonproductive cough. The patient initially notices dyspnea only during heavy exertion, but in very advanced stages of the disease, dyspnea occurs at rest. Diagnosis The occupational and environmental history is the single most helpful tool to determine whether a respiratory problem may be related to an environmental exposure Diseases in other organs may present as ILD, so a detailed review of systems is important (ROS) Abnormalities on chest x-ray may be the first clue to the presence of ILD; however, the patient with ILD may be asymptomatic or symptomatic with either normal or abnormal chest x-ray results. The initial abnormality on the chest x-ray film is usually described as a ground glass, A scattered reticulonodular pattern or hazy appearance of the lungs PFT: Normal FEV 1 /FVC ratio but decreased FVC and FEV 1 ; decreased total lung capacity, residual volume, and functional residual capacity. Residual volume–to–total lung capacity ratio is normal to low. A transbronchial biopsy is the leading invasive tool for evaluating and treating patients with a wide spectrum of pulmonary disorders. DLCO is a good reflection of alveolar capillary surface area. Destruction of lung parenchyma results in a reduction in DLCO as ILD progresses. An abnormal DLCO(decrease in single breath diffusing lung capacity for carbon monoxide) may be the earliest evidence of ILD found on standard PFTs. Management Ø The first course of action when faced with a patient with ILD is to determine whether exposure to environmental agents or drugs is the cause and to discontinue the exposure Ø Second, the best chance for therapeutic success begins with the correct diagnosis. Ø Finally, in cases in which specific medication is used, such as prednisone or cytotoxic agents, there is usually suppression rather than cure of the primary process. Initial Management Ø Corticosteroids 1 to 2 mg/kg/day, or 60 to 100 mg/day Ø Cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan), an alkylating drug, is a potent immunosuppressant and seems to be effective in patients with ILD who are not helped with corticosteroids. Cytotoxic agents, including azathioprine (Imuran) and cyclophosphamide (Cytoxan), are given concurrently with prednisone or in place of it if the patient cannot tolerate high-dose prednisone therapy Self-care measures: Ø Pulmonary medications Ø Diet Fluid intake Ø Smoking cessation Ø Environmental control Awareness of early signs of infection Ø Chest therapy: Relaxation and guided imagery Breathing retraining Controlling dyspneic episodes Postural drainage Ø Progressive exercise conditioning: Walking programs Treadmill or bicycle exercise training Arm or leg range-of-motion exercises Ø Respiratory equipment: Oxygen therapy Handheld nebulizer Prevention/Prophylaxis: Give patients pneumococcal, pneumonia and influenza vaccines • Types Community Acquired Pneumonia (CAP) o Signs and symptoms Typical symptoms include fever, chills, cough, and rusty or thick sputum, with associated gastrointestinal upset or anorexia, malaise, and diaphoresis; pleuritic chest pain may also be present, crackles. Older patient - mental status changes, falls, inc. resp. rate, hypotension, anorexia, new onset of urinary incontinence (Kennedy-Malone, p. 192-193). o Diagnostic criteria CURB -65 (each criteria worth 1 pt) C - Confusion U - BUN >19 ng/dL R - Respiratory rate ≥ 30 breaths/min B - BP: Systolic <90 mm Hg OR Diastolic <60 mm Hg Scoring : Low risk; consider outpatient treatment 2: Brief hospitalization or closely monitored outpatient treatment ≥ 3: Severe, hospitalize and possible ICU o Radiographic findings chest x-ray is considered the gold standard for the diagnosis of pneumonia; C-reactive protein (CRP) and/or urine specific antigen when there is a question about when, or if, to start antibiotic therapy ; CT scan of the chest is often ordered and is more accurate than a chest x-ray; Pulmonary infiltrate, lobular consolidation, or opacities found on chest x-ray, CT scan, or ultrasound confirm the diagnosis of pneumonia Obstructive & Restrictive Airway Disease o Understand the PFT interpretation for both https://www.alphanetbfrg.org/pdfs/Understanding-PFT.pdf ● Obstructive pattern ○ Decreased FEV1, normal or decreased FVC, and decreased FEV1/FVC ○ Classically, these are the patients with asthma, chronic bronchitis, or emphysema ■ PFTs can help further distinguish between the above three: ■ Bronchodilator responsiveness - an increase in the FEV1 by 12% following bronchodilator use suggests asthma ■ Bronchial provocation - inducing asthmatic obstruction of reactive lower airways by administering methacholine, histamine, or adenosine monophosphate ■ DLCO will be decreased in patients with emphysema, and can be normal or increased in patients with asthma ○ Lower airway obstruction vs. upper airway obstruction ■ Lower airway obstruction typically displays impaired expiratory capacity (see image below), while upper airway obstruction has impaired inspiratory capacity, which can be evident on the flow volume loop (seen as flattening of the inspiratory arm). ● Restrictive pattern ○ Decreased TLC, FEV1, and FVC with a normal FEV1/FVC, and a low DLCO ○ Typically these are patients with interstitial lung disease, severe skeletal abnormalities, or diaphragmatic paralysis ○ The flow volume loop is generally normal in appearance, but has low lung volumes o Spirometry ● PFTs can be used in a variety of settings, and they are generally ordered to: ○ Look for evidence of respiratory disease when patients present with respiratory symptoms (e.g. dyspnea, cough, cyanosis, wheezing, etc.); ○ Assess for any progression of lung disease; ○ Monitor the efficacy of a given treatment; ○ Evaluate patients pre-operatively; and ○ Monitor for potentially toxic side effects of certain drugs (e.g. amiodarone) ● The components of PFTs include: ○ Lung volumes ○ Spirometry and flow volume loops ○ Diffusing capacity o Know definitions for each spirometry criteria Spirometry measures two key factors: expiratory forced vital capacity (FVC) and forced expiratory volume in one second (FEV1). Your doctor also looks at these as a combined number known as the FEV1/FVC ratio. If you have obstructed airways, the amount of air you’re able to quickly blow out of your lungs will be reduced. This translates to a lower FEV1 and FEV1/FVC ratio. Forced vital capacity (FVC). This is the largest amount of air that you can forcefully exhale after breathing in as deeply as you can. A lower than normal FVC reading indicates restricted breathing. Forced expiratory volume (FEV). This is how much air you can force from your lungs in one second. This reading helps your doctor assess the severity of your breathing problems. Lower FEV-1 readings indicate more significant obstruction. o Know criteria to determine severity (FEV1) https://goldcopd.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/GOLD-2019-POCKET-GUIDE-DRAFT-v1.7- 14Nov2018-WMS.pdf o Know criteria for diagnosis of obstruction (FEV1/FVC ratio) An FEV1/FVC <80% suggests obstructive lung disease, while restrictive lung disease typically has normal or increased FEV1/FVC o Know criteria for diagnosis of reversible versus irreversible FEV 1 /FVC ratio before and after bronchodilator challenge, showing an improvement of 12% and 200 mL, indicates reversible airway obstruction Sleep apnea o Diagnostic criteria - Sleep apnea is defined as a temporary pause in breathing during sleep that lasts at least 10 seconds. For a confirmed diagnosis, this should occur a minimum of five times an hour. o Signs and symptoms- Hypersomnolence is the single most important presenting symptom of sleep apnea Daytime symptoms include a morning headache (from hypercapnia) and neuropsychological disturbances, including falling asleep while performing purposeful activities. The patient may complain of nocturnal restlessness, frequent urination or enuresis, and choking. Patients also may report impaired intellectual performance, such as decreased concentration, ambition, and memory loss. The predominant physical examination findings of OSA reflect the risk factors: obesity (particularly of the upper body), increased neck size, crowded oropharynx (tonsillar hypertrophy and enlargement of soft palate [uvula] and tongue). Week 3 Mood disorders Anxiety o Signs and symptoms Excessive worrying that is difficult to control and interferes with daily life; can also manifest with somatic symptoms such as chest tightness, shortness of breath, upset stomach. Predictors of late-onset anxiety include female gender, recent adverse life events, illness, cognitive impairment, and mental illness comorbidities, while poverty and poor psychological support during earlier years also contribute (Zhang et al., 2015). Comorbid dementia or depression are not uncommon in older patients experiencing anxiety Signs and Symptoms: May include a sense of impending doom, trembling, breathlessness, and tachycardia. Anxiety may impair working memory, attention, and problem-solving skills (Andreescu & Varon, 2015). In older adults, somatic complaints are more common, such as constipation, nausea, and sleep disturbance. Worries about health, disability, and finances are also common. One is more likely to learn of a patient’s anxiety by asking the question, “How do you feel when you are under stress?” than by asking, “Are you anxious?” (National Institute of Mental Health, n.d.). Patients with specific phobias may have an irrational fear to something that poses little danger, such as fear of crowds or natural phenomena (heights, lightening). Specific phobias may occur following a traumatic event, such as falling. Symptoms of anxiety in older adults often overlap with symptoms of physical disorders, depression, and dementia (Koychev & Klaus 2016). generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), social anxiety, specific phobia, and anxiety disorder related to substance use, medication, or another medical condition. Panic disorder and agoraphobia are less common in older adults o Diagnostic criteria A diagnosis of GAD according to the DSM-5 requires excessive anxiety, difficulty controlling worry, and associated symptoms (at least three) including restlessness, easy fatigability, difficulty concentrating, irritability, muscle tension, difficulty falling or staying asleep, or restlessness (APA, 2013) Diagnostic Tests: Complete a history and physical examination. Laboratory tests can rule out medical conditions with anxiety symptoms, including complete blood count (CBC), CMP, and TSH. Order additional tests based on the findings of the history and physical examination. Valid assessment scales to help diagnosis and assess older adults for anxiety include the Geriatric Anxiety Inventory (GAI) and the Geriatric Assessment Scales (Clifford et al., 2015; Gould et al., 2014). Differential Diagnosis: Includes medical conditions (hypoglycemia, hyperthyroidism, pain, brain tumor, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], etc.) and substance use that precede new-onset anxiety symptoms. Many cardiac, respiratory, endocrine, hematologic, and neurological conditions may be associated with anxiety (Andreescu & Varon, 2015; Allahverdipour, Asghari-Jafarabadi, Heshmati, & Hashemiparast, 2013; Uchmanowicz, Jankowska-Polanska, Motowidlo, Uchmanowicz, & Chabowski, 2016). Medications, including anticholinergic drugs, dopamine agonists, levothyroxine, steroids, psychostimulants, and over-the-counter (OTC) sympathomimetics may be anxiogenic. Depression and dementia commonly overlap with anxiety in older adults (Andreescu & Varon, 2015; Lenze et al., 2015; Vasiliadis et al., 2013). o 1st line treatment (mild, moderate, severe) Treatment: Treatment for anxiety should reduce symptoms and improve functioning. Simply listening, being compassionate, and showing respect are important to improving outcomes. Comorbid depression and medical conditions should be treated. There are no large-scale studies of pharmacotherapy for late-life anxiety disorders to guide treatment decisions, as randomized controlled trials largely exclude those more than 65 years old. Evidence from studies with younger patients suggests both pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy, especially CBT, are effective. “Start low and go slow” with medication dosing to avoid risks from drug interactions. Older adults are more likely to take many medications and may have side effects from aging changes in absorption, metabolism, distribution, and excretion of medication. Doses are often started at half the usual adult starting dose and titrated slowly upward. Evaluate and manage side effects, because as many as 25% of patients stop taking medication in the first 6 months due to side effects. First-line treatment includes the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) because they have the least risk of drug interactions, side effects, or worsening existing medical conditions. Escitalopram, sertraline, and citalopram are commonly used in older adults (Clifford et al.; Shaw, 2015; Koychev & Klaus, 2016), although citalopram should not be used routinely in doses above 20 mg daily due to prolongation of QT interval precautions. GI disturbances, sexual dysfunction, and altered mental status due to hyponatremia may occur. Serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), including Venlafaxine and Duloxetine, have been shown to be effective in older adults with anxiety (Andreescu & Varon, 2015). Blood pressure should be monitored with high doses of SNRIs. Benzodiazepines, including lorazepam, alprazolam, and clonazepam, are effective (Andreescu & Varon, 2015) and may be used as a bridge until the SSRI takes effect. They are not the first choice due to the risk of falls and confusion. Buspirone and gabapentin are also used as secondary agents when first-line therapy fails and anxiolytic therapy is warranted (Andreescu & Varon, 2015; Baldwin et al., 2014). Research supports psychotherapy, especially CBT, for older adults with GAD (American Psychiatric Association, n.d.; Baldwin et al., 2014; National Institute of Mental Health, n.d.). CBT may augment SSRIs to further reduce worry symptoms and relapse (Lenze et al., 2015). However, in some cases, CBT may be counterproductive because cognitive reappraisal can trigger additional worry due to over-engagement of the amygdala and under-engagement of the pre-frontal cortex in older adults with anxiety (Andreescu et al., 2015). Preliminary findings on mindfulness-based relaxation therapy in older adults is promising in reducing worry (Lenze et al., 2014), although further study is necessary. o Medication management Maintenance SSRI use has been shown to reduce relapse of anxiety in older adults (Baldwin et al., 2014; Lenze et al., 2015). SSRIs can increase anxiety if started at higher doses. It may take several weeks for full effect to occur. Follow-Up: Evaluation of the effectiveness and tolerability of treatment depends on the severity of symptoms and impairment in functioning. Older adults may not be able to describe terms consistent with anxiety, thus it is necessary to allow them to use their own words, allow extra time for questioning, and avoid complex terminology. Bipolar Depression o Signs and symptoms Signal Symptoms: Variable presentation ranging from depression to mania or hypomania, feelings of grandiosity, rapid speech, or irritability. Up to 22% of older adults with bipolar disorders experience anxiety symptoms (Dols et al., 2014). Cognitive deficits affecting verbal fluency and memory are common in older adults (Martino, Strejilevich, & Manes, 2013; Sajatovic & Chen, 2016; Wu et al., 2013). The depressive symptoms often include trouble with eating and sleeping (Kontis, Theochari, & Tsalta, 2013). Description: Bipolar disorders, according to the APA (2013), are classified as 1. Bipolar I disorder requires an individual to have experienced at least one manic episode. A manic episode involves a change in mood that may be expansive, euphoric, or irritable, and accompanied by an increase in energy level. Most patients also have depressive episodes, but this is not a required component. 2. Bipolar II disorder requires at least one prior episode of major depression and at least one hypomanic episode, a milder form of mania. 3. Cyclothymic disorder is characterized by milder mood alterations that occur over a longer period of time, while unspecified bipolar disorder consists of symptoms that cause clinical impairment but do not meet criteria for the previously mentioned listings (APA, 2013). 4. Other specified bipolar and related disorders Each depends on the presentation and intensity of symptoms. It is important to distinguish bipolar disorder from major depression, as treatment differs (Beyer, 2015). Signs and Symptoms: • Elevated mood, presenting as euphoria or irritability • Dysphoria, manifesting with depression alone or with irritability • Rapid cycling includes back-and-forth shifts from mania to depression. • Inquiring about suicide ideation or intent should be addressed at every visit. • Psychotic symptoms can present in either manic or depressed states, and cognitive impairment is common • The acronym DIGFAST has been used to describe signs and symptoms during a manic or hypomanic phase. According to the DSM-5, the individual must also experience increased energy while having these symptoms ■ Distractibility ■ Insomnia ■ Grandiosity ■ Flight of ideas ■ Activities (hyperactive, does not require rest) ■ Speech (rapid, can be garbled) ■ Thoughtlessness (impulsivity) Symptoms during the depressive phase are similar to those of major depression. Use the acronym SIGECAPS: ■ Sleep disturbance ■ Interest/pleasure reduction ■ Guilt feelings, thoughts of worthlessness ■ Energy changes/fatigue ■ Concentration/attention impairment ■ Appetite/weight changes ■ Psychomotor disturbances ■ Suicidal thoughts o Diagnostic criteria Diagnostic Tests: The Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) is a validated (Hirschfeld et al., 2003, 2000) screening tool to assess for bipolar spectrum disorder, however, is not specific to older adults. The tool can be accessed at www.integration.samhsa.gov/images/res/MDQ.pdf. For patients with depressive features, the Geriatric Depression Scale, regular (www.stanford.edu/~yesavage/GDS.english.long.html) or short form (www.stanford.edu/~yesavage/GDS.english.short.score.html), is recommended as a screening tool. Diagnostic studies include a • CBC • Comprehensive metabolic panel (CMP) • Toxicology screen • Uinalysis • Thyroid function tests • Rapid plasma reagin (RPR) • HIV • Electrocardiogram (EKG) • Other individualized testing as indicated by the individual patient presentation and anticipation of treatment modalities In patients with new onset of psychosis: • Electroencephalogram (EEG) • Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) • Computed tomography (CT) scan may be appropriate to rule out medical pathologies. Other screening tests for cognitive disorders: • Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) • Saint Louis University Mental Status (SLUMS), which is more sensitive to detecting cognitive impairment, may be useful in assessing comorbid neurocognitive deficits o First Line Treatment Treatment: The goal is remission of symptoms. There are no specific guidelines specific to older adults, however, practice guidelines generally suggest similar pharmacological treatment for older adults as with younger adults Patients with bipolar disorder are often challenging to manage because of the fluctuating and chronic nature of bipolar disorder. Depending on the presentation and severity, inpatient treatment may be required to stabilize the patient. First-line treatment for late-life mania includes: • mood stabilizers lithium and valproic acid • antipsychotics, quetiapine and olanzapine Because older adults are frequently on multiple medications for other comorbid conditions, monotherapy has been recommended as a starting point with a backup plan for adding other drugs as indicated. Patients with coexisting dementia require individualized treatment, and co-management by a geriatric psychiatrist is advised. There is early evidence of a neuro-protective affect for developing dementia in those prescribed lithium Drug therapy is specific to different bipolar disorder states Bipolar Mania U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-Approved Drugs ■ Anticonvulsant mood stabilizers: Lithium, valproic acid, divalproex, or carbamazepine (second line) ■ Antipsychotics: Olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine, ziprasidone, aripiprazole, asenapine Bipolar Acute Depression FDA-Approved Drugs ■ Anticonvulsants: Lithium ■ Antipsychotics: Quetiapine, lurasidone, olanzapine-fluoxetine combination. Bipolar Maintenance FDA-Approved Drugs ■ Mood stabilizers: Lithium, lamotrigine, valproic acid ■ Antipsychotics: Olanzapine, aripiprazole, quetiapine, risperidone, ziprasidone Treatment may require a combination of the previously mentioned medications Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) is highly effective in resistant cases of bipolar depression and should be considered if drug therapy is ineffective o Medication management Dosing should begin at the lowest dose and be slowly increased, while monitoring comorbidities and adverse effects. Benzodiazepines are sometimes used for acute agitation in mania. SSRIs are generally not recommended for bipolar depression, as they are often ineffective and can induce mania; however, they are used in selective, resistant cases. A collaborative care model has been successful for patients with combined chronic medical and mental health problems Establishing a therapeutic alliance is key to management; psychotherapy and psycho-education are also an important part of treatment o Medication metabolic effects Follow-Up: Regular follow-up, particularly during active periods of mania or depression, is essential and should include monitoring for suicide. Family members are usually included because bipolar disorder affects the entire family. Lithium requires • initial evaluation of renal, cardiac, and thyroid function before initiating therapy, and then periodically during therapy. • Lithium levels also need close monitoring during the initial period and periodic monitoring once stabilized. • Concurrent use of NSAIDs, thiazide or loop diuretics, and angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors may adversely affect lithium levels • Adverse effects include o tremor o hypothyroidism o weight gain o cognitive and renal impairment Valproic acid also require close monitoring; • drug levels, liver function tests (LFTs), and CBC should be checked. • Adverse effects include weight gain, hepatotoxicity, pancreatitis, and thrombocytopenia. Atypical antipsychotics • have weight, glucose, and lipids monitored. • QT interval prolongation can also occur. • prescribed for older adults with dementia? àfound to increase mortality; this could be translated to those with bipolar disorder Unipolar Depression o Signs and symptoms Pervasive and sustained mood of sadness, discouragement, lack of pleasure in usual activities, guilt, loss of motivation, low energy, and sleep and/or appetite disturbances. Depression is described as a pervasive feeling of sadness or a lack of interest or pleasure in previously enjoyed or usual activities. Feelings of guilt, low self-esteem, sleep and appetite disturbances, low energy, and poor concentration are common. Late-life depression is defined as a new onset of depression occurring in one’s sixties. Depression may be categorized as • a single episode or recurrent • further qualified as mild, moderate, or severe • with or without features such as melancholy, mood-congruent, catatonia, peripartum onset, or with seasonal pattern. Types of geriatric depression include • MDD • Vascular depression o The comorbidity of depression, vascular disease, vascular risk factors, and the association of ischemic cerebral lesions with distinctive behavioral symptoms supports the “vascular depression” hypothesis. This hypothesis proposes that cerebrovascular disease may predispose, precipitate, perpetuate, or exacerbate some geriatric depressive syndromes • Dysthymia • Depression that manifests as a comorbid condition in dementia, bipolar disorder, and executive dysfunction Depression is not a normal part of the aging process. Causative factors for depression include • Physiological influences such as o medication side effects o neurological disorders o cardiac disease o neuroendocrine disturbances o electrolyte and hormonal disturbances o nutritional deficiencies in vitamin B12. o Vitamin D deficiency strongly correlates with depression, raising the risk of depression two-fold • Psychosocial and cognitive theories postulate o internalized loss with ego dysfunction o learned helplessness o loss and bereavement o cognitive distortions with negative attitudes and thoughts o Difficulty accomplishing developmental tasks associated with life stages may contribute to and/or be a consequence of depression. o Environmental and social factors contribute to depression when major stressors occur and social support systems are inadequate. • Biological theories point to o impaired synthesis o deficiencies o increased uptake o increased metabolism or breakdown of the neurotransmitters serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine Genetics: Higher risk of depression among those with siblings or parents with depression. Psychosocial: Single or multiple losses: loved ones, independence, mobility, function, financial security, autonomy, privacy, social network; changes in environment; admission to health-care facility; limited social support, loneliness, negative life events. Physical Illnesses: Diabetes, cancer, Parkinson’s disease, AD, cerebrovascular accident, obstructive sleep apnea, vascular brain lesions, heart disease, arthritis, hypothyroidism, vitamin deficiencies, anemia, COPD, any chronic illness/pain syndromes, disabilities. Psychiatric Illnesses: Alcohol, substance abuse, family or personal history of psychiatric illness or depression Medications: Anxiolytics, sedatives/hypnotics, antipsychotics, cardiac medications, antihypertensives, beta blockers, H2 blockers, narcotic analgesics, and steroids, either alone or in combination with other medications (monotherapy, polypharmacy, drug–drug interactions), can cause behavioral, affective, and cognitive changes. The Beers list and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) unnecessary medications list indicate medications to avoid prescribing for the elderly Special attention should be paid to medications affecting kidney function and the potential for drug-to-drug interactions. Signs and Symptoms: Symptoms of depression may encompass four domains: 1. Affect/mood 2. Cognition • Sadness, anhedonia, apathy, helplessness, hopelessness, worthlessness, and loneliness • Ambivalence, uncertainty, inability to concentrate, confusion, poor memory, slowed speech, lack of motivation, a pessimistic outlook, negative thoughts, self-criticism, and poor self-esteem • Perceptual disturbances, such as hallucinations, illusions, and delusions, to determine if psychotic features of an agitated depressive episode are present 3. Physiological • Sleep, appetite, and energy disturbances; weight change; constipation; pain; headache; decreased libido; sexual non-responsiveness; and exaggerated concerns over bodily functions 4. Behavior • psychomotor retardation or agitation, irritability, poor personal hygiene, tearfulness, and social withdrawal ********It is of paramount importance to question the patient about suicidal ideation and/or plans and assess accessibility to lethal weapons. Some patients experience excessive worry, preoccupation, and generalized anxiety. Clinical presentation may include inattention to personal appearance, poor hygiene, poor eye contact, and a blunted or flat affect; many of these manifestations appear similar to dementia or The DSM-5 (APA, 2013) diagnostic criteria for MDD include sustained, disruptive, and pervasive depressed mood or loss of interest or pleasure. With the exception of suicidal ideation and weight change, five or more of the following symptoms must be present for most of the day, on most days, over a 2-week period: ■ Depressed mood as reported in subjective report or as observed by others ■ Obsessive rumination or worry ■ Change in appetite and significant change in weight ■ Change in sleep pattern: insomnia (difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep, waking earlier than necessary, inability to fall back asleep), hypersomnia, frequent napping ■ Psychomotor agitation or retardation (including as observed by others) ■ Fatigue or loss of energy ■ Feelings of hopelessness ■ Feelings of worthlessness, excessive guilt ■ Diminished concentration, indecisiveness ■ Recurrent thoughts of death, suicidal ideation or gestures, suicide attempt, suicide plan Distinct clinical manifestations in older adults include: ■ Report of lack of emotions (versus depressed mood) ■ Excessive concern with bodily functions ■ Seeking reassurance and support ■ Isolative, withdrawn behavior ■ Change in previous level of function, decline in ADLs ■ Feeling overwhelmed, easily frustrated, excessive crying ■ Irritability, fearfulness, agitation, anxiety ■ Transient, recurring symptoms, diurnal fluctuations or pattern ■ Minimizing expressed death wishes or passive suicidal behavior At the first encounter, the patient should be interviewed individually. Goals of the interaction should include establishing a therapeutic, trusting alliance, which can then enhance the discussion of sensitive topics such as sexuality, abuse, and suicidal thoughts. The subjective history should begin with open-ended questions, which can then be followed by specific and focused questions. The history should include present illness, past psychiatric history, family history including mental health, medical history, prescription and OTC medication use, social history (education, work history, important relationships, sexual activity, spirituality, and current living arrangements), and functional assessment. Assessment should include a comprehensive physical examination to look for secondary causes of depressive symptoms, a full mental health assessment, and a mental status examination if confusion or cognitive impairment is manifested. o Diagnostic criteria Diagnostic Tests: Diagnostics to assess for underlying or undiagnosed medical causes of depressive symptoms should be ordered. Standard blood work includes: • CBC with differential • CMP • lipid panel • thyroid function studies (TSH with reflex T4) • serum vitamin B12 • serum vitamin D levels. Depression Scales ■ Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS, long and short forms) ■ Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) ■ Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ–9) ■ Hamilton Depression Scale (HAM-D) ■ Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology—Self-Report (QIDS-SR) ■ Scale for Suicide Ideation Overall Cognitive Functioning ■ Folstein’s Mini-Mental Status Exam (MMSE) o 1st line treatment (mild, moderate, severe) While the tricyclics (TCAs) and mono-amine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) are still available, these are no longer considered first-line recommendations. o Medication management Monitor and evaluate therapeutic response to antidepressant therapy, and observe for side effects, tolerance, and unremitting symptoms of depression. Studies show that the majority of patients on a single agent (monotherapy) do not tolerate it, have limited or no response, stop the medication within the first 3 months, or never receive an adequate dose or trial of medication. Consequently, monotherapy is effective in approximately one-third of patients, and the great majority do not reach remission. • For those patients who do not respond adequately to monotherapy, other treatment strategies may be employed. • Switching agents within the same class or combining different types of antidepressants (e.g., a combination of sertraline and bupropion) may result in symptom remission. With multiple failed trials of monotherapy or combination therapy, the patient may be considered to have treatment-resistant depression. • Several second-generation antipsychotic agents are FDA approved for augmentation to antidepressant therapy in treatment resistant depression: o aripiprizole (Abilify) o quetiapine extended release (Seroquel XR) o olanzapine (Zyprexa) Length of Pharmacotherapy Treatment and Follow-Up: When initiating or changing the dose of antidepressant medication, it is critical to monitor the patient closely for efficacy and side effects. Observe for: • worsening of depression • suicidal thoughts or actions • unusual changes in behavior • agitation • irritability Factors that increase risk for suicide include • severe insomnia • being a member of a sexual or cultural minority • chronic pain or disability • family history of suicide (especially in the same-sex parent) • previous suicide attempts • loss of a loved one • lack of employment • increased financial burden Every patient should be screened for suicidal thoughts during pharmacological initiation, dosing phases, and at every subsequent encounter. A return office visit every 2 to 4 weeks is strongly recommended; if a physical visit is not possible, telephone contact should be made Length of antidepressant treatment varies depending on whether it is a first or recurrent episode. With each recurrence, there is an increased risk of future recurrence if medication is discontinued, and as a result, antidepressant therapy must be maintained for longer periods of time if not indefinitely. The acute phase of treatment lasts up to 3 months after the start of medication, with the goal to achieve remission. Close follow-up is critical and highly individualized; however, there should be patient contact within the first month and additional contact every 4 weeks or sooner with dosage adjustments, switching, combination, or augmentation. The continuation phase of treatment begins once remission is achieved, and medication should be continued for at least another 4 to 12 months. With one lifetime episode of MDD, a trial discontinuation of medication is optional if the patient has remained asymptomatic for the duration of the continuation phase of treatment. Patients in the continuation phase of treatment should be seen every 5 or 6 months or sooner. The maintenance phase of antidepressant therapy is specifically for patients with two or more lifetime episodes of MDD. These patients should be maintained on medication at the same dosage for another 15 months to 5 years. Patients in the maintenance phase of treatment should be seen every 6 to 12 months or sooner. Psychotherapy: Many patients continue to experience distressing symptoms of depression despite one or even several pharmacological interventions. Research studies demonstrate that supportive counseling, psychotherapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, problem-solving therapy, interpersonal psychotherapy, reminiscence therapy, group therapy, and support groups improve remission and recovery rates when patients actively participate (Francis & Kumar, 2013). For patients with mild depression, therapy alone may be sufficient as a treatment strategy. Those with moderate to severe depression experience significantly better outcomes with concurrent psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy. Complementary and Alternative Therapies: Complementary or alternative treatment modalities may be effective at preventing or reduce depressive symptoms. Evidence supports dietary or supplemental intake of omega-3 fatty acids and vitamin D. St. John’s wort has been shown to reduce depressive symptoms among elder patients. Additional minerals, vitamins, and herbs that may help to reduce depression include SAMe and folic acid. However, these alternative modalities are not without risk and should not be recommended lightly. It is important to consider which supplements may induce the metabolism of other medications, which inhibit metabolism, which are metabolized by the cytochrome P450 enzymes, and which may increase the risk of vascular bleeding (Nyer et al., 2013). Patients should be encouraged to engage in activities that promote physical and mental wellness: • exercise, tai chi, massage, and yoga • aerobic exercise reduces the somatic symptoms of depression, although moderate exercise may not be as effective for older frail adults residing in long-term care facilities. • Some older adults benefit from spiritual or religious therapy. • Engaging with music actively (playing or composing) and listening has several benefits, including promoting mental well-being, facilitating expressions of emotions, and enhancing antidepressant medication therapy Follow-Up: ■ Use diagnostic scales/instruments (symptom and severity tools) to objectively assess progress compared to baseline evaluation. ■ Assess for therapy and medication adherence, response, and side effects. ■ Assess suicidal ideation. ■ Titrate medication dose for total remission. ■ If trial discontinuation, taper over 2 to 4 weeks. ■ Monitor for early signs of recurrence. Sleep/ Wake Disorders A. Underlying medical causes of sleep/wake disorders • Painful conditions, such as arthritis and muscle cramps • Fibromyalgia • Delirium or dementia (“sundowning”) • Acid reflux, gastroesophageal reflux disease, or duodenal ulcers • Conditions causing shortness of breath • Thyroid disease • Obesity (also associated with sleep apnea) • Substance use, intoxication, or withdrawal • Pregnancy or postpartum • Nocturia • Side effect of a medication B. Underlying psychological causes of sleep/wake disorders • Major depressive disorder • Generalized anxiety disorder • Manic episode • Psychotic illness, such as schizophrenia • Traumatic events precipitating acute insomnia • Post-traumatic stress disorder leading to hyperarousal • Poor sleep hygiene • Other sleep-wake disorders (OSAH, RLS) Insomnia (Kennedy-Malone p. 461). o Signs and symptoms Report of not sleeping, excessive daytime sleepiness, loud snoring (sleep apnea), restless legs, difficulty falling asleep and staying asleep, irritability, difficulty concentrating, sleep that is not refreshing and restful, daytime fatigue, an older adult may spend 10 to 12 hours in bed at night trying to sleep o Diagnostic criteria insomnia is a clinical diagnosis, sleep history should include an assessment of daytime sleepiness, fatigue, or sleep disturbance; the sleep environment; and the duration of symptoms. Additionally, information on frequency and duration of awakenings, sleep times, nap times, and lengths is important o 1st line treatment for chronic insomnia Chronic insomnia *Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT)* Thorough family hx (inc. sleep problems), A validated self-administered instrument, such as the Epworth Sleepiness Scale or Stanford Sleepiness Scale, sleep diary, interrogate sleep partner (if any), If sleep apnea is suspected, refer for polysomnography, review sleep hygiene tips (Combined, sleep hygiene instruction and cognitive behavioral therapy are more effective than either modality alone or usual treatment), music therapy, aerobic exercise Transient insomnia avoid caffeine 12 before bedtime, D/C ETOH and sleep-interrupting drugs, OTC melatonin, if ineffective, a short-acting sedative-hypnotic, such as zolpidem (Ambien) or zaleplon (Sonata), at lowest dosage before desired bedtime for 1 week or less (space to avoid S/E), benzodiazepine - short-acting- temazepam (Restoril). o Medication management Chronic insomnia temazepam (Restoril) for sleep onset insomnia eszopiclone (Lunesta) for sleep onset and sleep maintenance zolpidem CR and zolpidem (AmbienCR and Ambien) zolpidem sublingual (Intermezzo) for sleep maintenance zaleplon (Sonata) and ramelteon (Rozerem) for sleep onset insomnia. All of these drugs are listed as potentially inappropriate medications (PIMs) on the Beers list (2015) to be avoided in older adults Transient insomnia zolpidem (Ambien) zaleplon (Sonata) temazepam (Restoril) Osteoarthritis morning stiffness lasting <30 mins but improves with activity. Also known as degenerative joint disease. It most commonly affects hips, knees and cervical and lumbar spine. While the joint deformity with minimal pain is usually found in the DIP and PIP joints of the hand and the first metacarpal joint and metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint. o Signs and symptoms o Radiographic findings Two views of the affected joint are recommended with the exception of the sacroiliac joint and the pelvis. Other types of imaging tests such as ultrasound and MRI may be used to detect damage to cartilage, ligaments and tendons, which cannot be seen on Xray. o 1st line treatment o Medication management Treatment: multifaceted approach • Walking • Water therapy • Acetaminophen • NSAIDs- cyclooxygenase type 2(COX-2) such as celecoxib (Celebrex) 50-100mg BID. In patients who can not afford COX-2 may try, nonacetylated salicylates such as Magnesium trisalycylate 500-750mg BID-TID. • Tramadol can be given at 50mg Q 4 -6 hours • Opiates such as codeine and oxycodone can be used for severe OA • Glucosamine and chondroitin Topical diclofenac sodium Osteoporosis o Signs and symptoms Signs and Symptoms: Patients with osteoporosis may be asymptomatic. • All patients more than 50 years old should be screened for fracture risk. • Patients need to be questioned about all the risk factors for osteoporosis. • Personal history of fractures? Family hx? Questions about libido and potency in men are important to determine secondary gonadal issues. • Most common fractures are those of the spine, hip, wrist, and distal forearm. • Exceptions are fractures of the fingers, toes, face, and skull, which tend to be more related to trauma than low bone mass o Diagnostic criteria Clinical tool developed to assist clinicians in the identification of patients at high risk for fractures: 1. FRAX: Fracture Risk Assessment Tool a. screen patients with low bone density who are not currently receiving treatment to help determine need for treatment b. integrates validated clinical risk factors and BMD of the femoral neck to calculate the 10-year probability of hip fracture and the 10-year probability of a major osteoporotic fracture (clinical spine, forearm, hip, or shoulder) c. not appropriate to use FRAX to monitor treatment response 2. DEXA Diagnostic Tests: Osteoporosis is defined based on the BMD measurement BMD is measured: • Dual-energy x-ray absorptiometry (DEXA or DXA) o The results are reported as T- and Z- scores § WHO T-score compares the bone mass of the patient to the mean of a young adult (20-year-old healthy woman) § Recommendations apply to postmenopausal women and men age 50 years and older § In premenopausal women, men less than age 50 years, and children, the International Society for Clinical Densitometry (ISCD) recommends the diagnosis of osteoporosis be made based on ethnic- or race-adjusted Z-score § A Z-score of –2 or less is defined as low BMD for chronological age and those above –2 are within the expected range for age • quantitative computed tomography (QCT) o QCT is three-dimensional and provides a true density measurement of the spine and hip. It can also determine trabecular and cortical bone separately. It is used less often due to the increased expense, greater exposure to radiation, and less reproducibility (meaning difficulty comparing results over time). • quantitative ultrasound (QUS) Vitamin D levels should be at least 77 µmol/L or 30 ng/mL because lower levels can result in secondary hyperparathyroidism and have been linked to an increase in other chronic diseases. When interpreting serum calcium level in older adults, it is important to correct for albumin level because 30% to 55% of calcium is bound to albumin. A falsely low measurement results when albumin is low. Every 1 g/dL of albumin binds 0.8 mg/dL of calcium. The correction adds 0.8 mg/dL for every 1 g/dL decrease in albumin. Ionized calcium measures free calcium, but it is an expensive test that is difficult to interpret; consultation before requesting may be helpful. o DEXA results: normal, osteopenia, osteoporosis § A Z-score of –2 or less is defined as low BMD for chronological age and those above –2 are within the expected range for age ● T-score of -1.0 or above = normal bone density ● T-score between -1.0 and -2.5 = low bone density, or osteopenia ● T-score of -2.5 or lower = osteoporosis o Medication management Treatment of osteoporosis should be considered for patients with low BMD, as well as a 10-year risk of hip fracture of 3% or more or a 10-year risk of a major osteoporosis-related fracture of 20% or more. GOAL: to prevent fractures Basic level of prevention and treatment includes diet, exercise, and fall prevention strategies. Adequate intake of calcium and vitamin D is essential to decrease bone loss and bone turnover. Vitamin D replacement is available in two forms, ergocalciferol (vitamin D2) or cholecalciferol (vitamin D3). optimal and safe range o Rheumatoid Arthritis (Kennedy-Malone, p.322) - incurable autoimmune condition that affects synovial joints in the body o Signs and symptoms Morning stiffness > 1 hr joint swelling & pain (small joints of hands, wrists, & feet) symmetrical inflammatory polyarthritis decreased physical function In older adults, constitutional symptoms with RA may include low-grade fever, weight loss, malaise, and depression. Clinical joint findings hyperflexion of the PIP joints flexion of the DIP joints (swan neck deformities) flexion of the PIP joints and extension of the DIP joints (boutonniere deformity) ulnar deviation of the metacarpophalangeal joint knee and ankle effusions skin should be checked for subcutaneous nodules, which are generally <1 to 3 cm in diameter - firm and fixed on palpation systemic evaluation eye examination - keratoconjuctivitis, scleritis, corneal ulcers lungs - pleuritis, pneumonitis cardiac examination -pericarditis nerve- nerve entrapment, sensory neuropathy o Radiographic findings blood tests rheumatoid factor (RF), CRP, ESR, anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies ( when accompanied by high RF titer), anti-CCP antibodies, CBC may show normochromic, normocytic anemia, mild leukocytosis, and thrombocytosis radiograph o 1st line treatment methotrexate - disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) o Medication management corticosteroids, analgesia, NSAIDs DMARDS - suppress immune system, may take up to 3 mos for full effect methotrexate - 5mg once/w, co prescribed with folic acid ■ Sulfasalazine ■ Leflunomide ■ Hydroxychloroquine TB and hep testing prior to tx TNF inhibitor biological agents etanercept, adalimumab, infliximab, certolizumab, golimumab, rituximab, abatacept [Show More]

Last updated: 3 years ago

Preview 1 out of 50 pages

Buy this document to get the full access instantly

Instant Download Access after purchase

Buy NowInstant download

We Accept:

Reviews( 0 )

$19.00

Can't find what you want? Try our AI powered Search

Document information

Connected school, study & course

About the document

Uploaded On

Feb 04, 2021

Number of pages

50

Written in

All

Additional information

This document has been written for:

Uploaded

Feb 04, 2021

Downloads

0

Views

127

.png)