NR 602 Array Midterm Study Guide (All Correct Study Guide) Download to Score ANR 602 Array Midterm Study Guide (All Correct Study Guide)

Signs of pregnancy

presumptive (subjective signs) Amenorrhea, nausea, vomiti

...

NR 602 Array Midterm Study Guide (All Correct Study Guide) Download to Score ANR 602 Array Midterm Study Guide (All Correct Study Guide)

Signs of pregnancy

presumptive (subjective signs) Amenorrhea, nausea, vomiting, increased urinary frequency, excessive fatigue, breast tenderness, quickening at 18–20 weeks

probable (objective signs) Goodell sign (softening of cervix) Chadwick sign (cervix is blue/purple)

Hegar’s sign (softening of lower uterine segment) Uterine enlargement

Braxton Hicks contractions (may be palpated by 28 weeks)

Uterine soufflé (soft blowing sound due to blood pulsating through the placenta) Integumentary pigment changes

Ballottement, fetal outline definable, positive pregnancy test (could be hydatidiform mole, choriocarcinoma, increased pituitary gonadotropins at menopause)

positive (diagnostic signs) Fetal heart rate auscultated by fetoscope at 17–20 weeks or by Doppler at 10–12 weeks

Palpable fetal outline and fetal movement after 20 weeks

Visualization of fetus with cardiac activity by ultrasound (fetal parts visible by 8 weeks)

Pregnancy and fundal height measurement

Signs of pregnancy (presumptive, probable, positive)

Pregnancy and fundal height measurement As pregnancy progresses, the fundus rises out of the pelvis (Figure 29-1). At 12 weeks’ gestation, the fundus is located at the level of the symphysis pubis. By week 16, it rises to midway between symphysis pubis and the umbilicus. By 20 weeks’ gestation, the fundus is typically at the same height as the umbilicus. Until term, the fundus enlarges approximately 1 cm per week. As the time for birth approaches, the fundal height drops slightly. This process, which is commonly called lightening, occurs for a woman who is a primigravida around 38 weeks’ gestation but may not occur for the woman who is a multigravida until she goes into labor

Naegele’s rule

Add seven days to the first day of your LMP and then subtract three months. For example, if your LMP was November 1, 2017: Add seven days (November 8, 2017). Subtract three months (August 8, 2017).

The EDD is calculated by adding seven days to the first day of the last menstrual period, subtracting three months and adding one year.

This formula is known as Naegele's Rule. For example, if the patient's last menstrual period, LMP, was on August 10, 2019, the EDD would be calculated as follows. LMP equals August 10, 2019 plus seven days. August 17, 2019, minus three months. May 17, 2019 plus one year and that equals May 17, 2020.

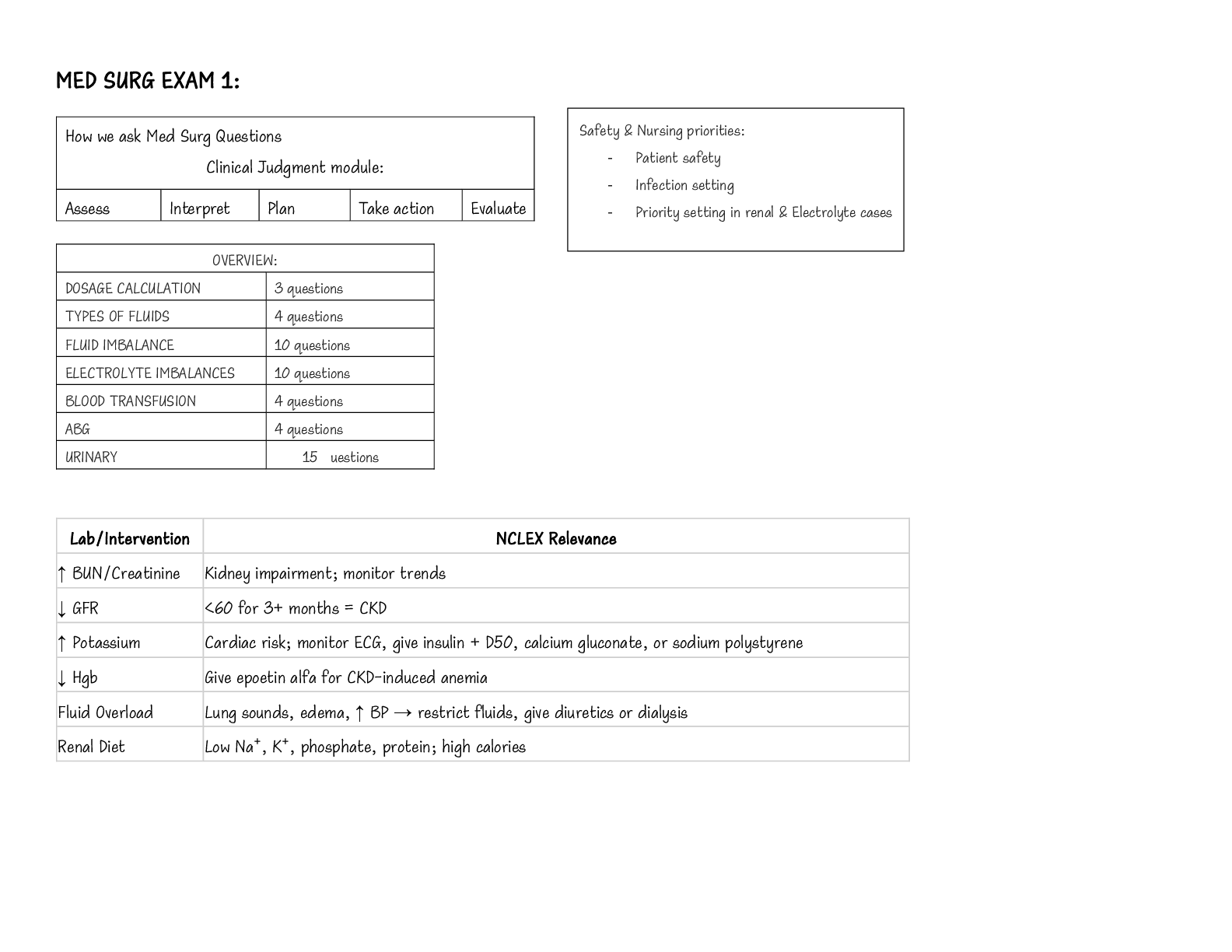

Hematological changes during pregnancy

During pregnancy, the heart is displaced upward and to the left within the chest cavity by the gravid uterus’s pressure on the diaphragm. As pregnancy progresses, the risk for inferior vena cava and aortic compression leading to supine hypotension increases when the woman lies in a supine position. To avoid hypotension and potential syncope, the woman should be advised to lie in a left lateral position. Hemodynamic changes and anatomic changes also may alter vital signs in the pregnant woman (Table 29-2).

Cardiac output in pregnancy increases by 30% to 50% over that in women who are not pregnant (Blackburn, 2013; Ouziunian & Elkayam, 2012). This increase peaks in the early third trimester and is maintained until birth. Half of the total increase in cardiac output, however, occurs by the eighth week of pregnancy (Blackburn, 2013). Therefore, women with cardiac disease may become symptomatic during the first trimester. Stroke volume is also increased during pregnancy by 20% to 30%. These increases in cardiac output and stroke volume allow for the 30% increase in oxygen consumption observed during pregnancy.

TABLE 29-2 Vital Sign Changes in Pregnancy

Vital Sign Changes in Pregnancy Measurement Alterations in Pregnancy

Heart rate and heart sounds Volume of the first heart sound may be increased with splitting. Third heart sound may be detected.

Systolic murmurs may be detected. Increases by 15–20 beats/min by 32 weeks’ gestation. Palpate the maternal pulse when auscultating the fetal heart rate to be able to distinguish between the two.

Respiratory rate Increases by 1–2 breaths/min None

BP First trimester: same as prepregnancy values

Second trimester: systolic BP decreases by 2–8 mm Hg and diastolic BP decreases by 5–15 mm Hg due to peripheral vascular resistance

Third trimester: gradually returns to prepregnancy values Use of an automated cuff may improve accuracy of measurement, as some pregnant women do not have a fifth Korotkoff sound.

Systolic and diastolic BP may be 16 mm Hg higher when taken while the woman is sitting.

BP readings may decrease in the maternal left lateral position.

Abbreviation: BP, blood pressure.

Data from Jarvis, C. (2016). Physical examination and health assessment (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier; Ouziunian, J., & Elkayam, U. (2012). Physiologic changes during normal pregnancy and delivery. Cardiology Clinics, 30, 317–329; Tan, E., & Tan, E. (2013). Alterations in physiology and anatomy during pregnancy. Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology, 27, 791–802.

During pregnancy, blood volume increases by 30% to 50%, or 1,100 to 1,600 mL (Ouziunian & Elkayam, 2012), and peaks at 30 to 34 weeks’ gestation. The increase in blood volume improves blood flow to the vital organs and protects against excessive blood loss during birth. Fetal growth during pregnancy and newborn weight are correlated with the degree of blood volume expansion.

Of the blood volume expansion occurring during pregnancy, 75% is considered to be plasma (King et al., 2015). There is also a slight increase in red blood cell volume

(RBC). The blood volume changes result in hemodilution, which leads to a state of physiologic anemia during pregnancy. As the RBC volume increases, iron demands also increase. Leukocytosis occurs in pregnancy, with white blood cell counts increasing to as much as 14,000 to 17,000 cells per mm3 of blood (Table 29-3). Clotting factors increase as well, creating a risk for clotting events during pregnancy.

Systemic vascular resistance is reduced due to the effects of progesterone, prostaglandins, estrogen, and prolactin. This lowered systemic vascular resistance, in combination with inferior vena cava compression, is partly responsible for the dependent edema that occurs in pregnancy. Epulis of pregnancy, or hypertrophy of the gums accompanied by bleeding, may also occur and is due to decreased vascular resistance and increase in the growth of capillaries during pregnancy (Jarvis, 2016).

Indications and contraindications for prescribing combined estrogen vs. progesterone-only birth control

Progestin-only contraceptives are used continuously; there is no hormone-free interval, as occurs with combined methods. These contraceptive methods have minimal effects on coagulation factors, blood pressure, or lipid levels and are generally considered safer for women who have contraindications to estrogen, such as cardiovascular risk factors, migraine with aura, or a history of VTE. In spite of this belief, the product labeling for some progestin-only products mimics the labeling for products containing estrogen.

The U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use (CDC, 2010;

see Appendix 11-A) can be used to identify appropriate candidates for progestin- only contraception.

Progestin-only contraceptives do not provide the same cycle control as methods containing estrogen, and unscheduled bleeding is common with all progestin-only methods. Typically, unscheduled bleeding occurs most frequently during the first 6 months of method use, with a substantial number of users becoming amenorrheic by 12 months of use (Hubacher, Lopez, Steiner, & Dorflinger, 2009). Overall blood loss decreases over time, making progestin-only methods protective against iron- deficiency anemia. With appropriate counseling, many women see amenorrhea as a benefit of these methods.

All progestin-only methods are likely to improve menstrual symptoms, including dysmenorrhea, menorrhagia, premenstrual syndrome, and anemia (Burke, 2011). The thickening of cervical mucus seen with progestin methods is protective against PID. Progestin-only contraceptives include the progestin-only pill (POP), an injection, an implant, and three progestin-containing intrauterine devices. The implant and devices are covered in the section on long-acting reversible contraception.

The U.S. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use (CDC, 2010) is a comprehensive, evidence-based guide for determining whether women have relative or absolute contraindications to contraceptive methods. The Medical Eligibility

Criteria uses the following four classification categories of whether a person can use or should not use a method:

• Category 1: a condition for which there is no restriction for the use of the contraceptive method

• Category 2: a condition where the advantages of using the method generally outweigh the theoretical or proven risks

• Category 3: a condition where the theoretical or proven risks usually outweigh the advantages of using the method

• Category 4: a condition that represents an unacceptable health risk if the contraceptive method is used

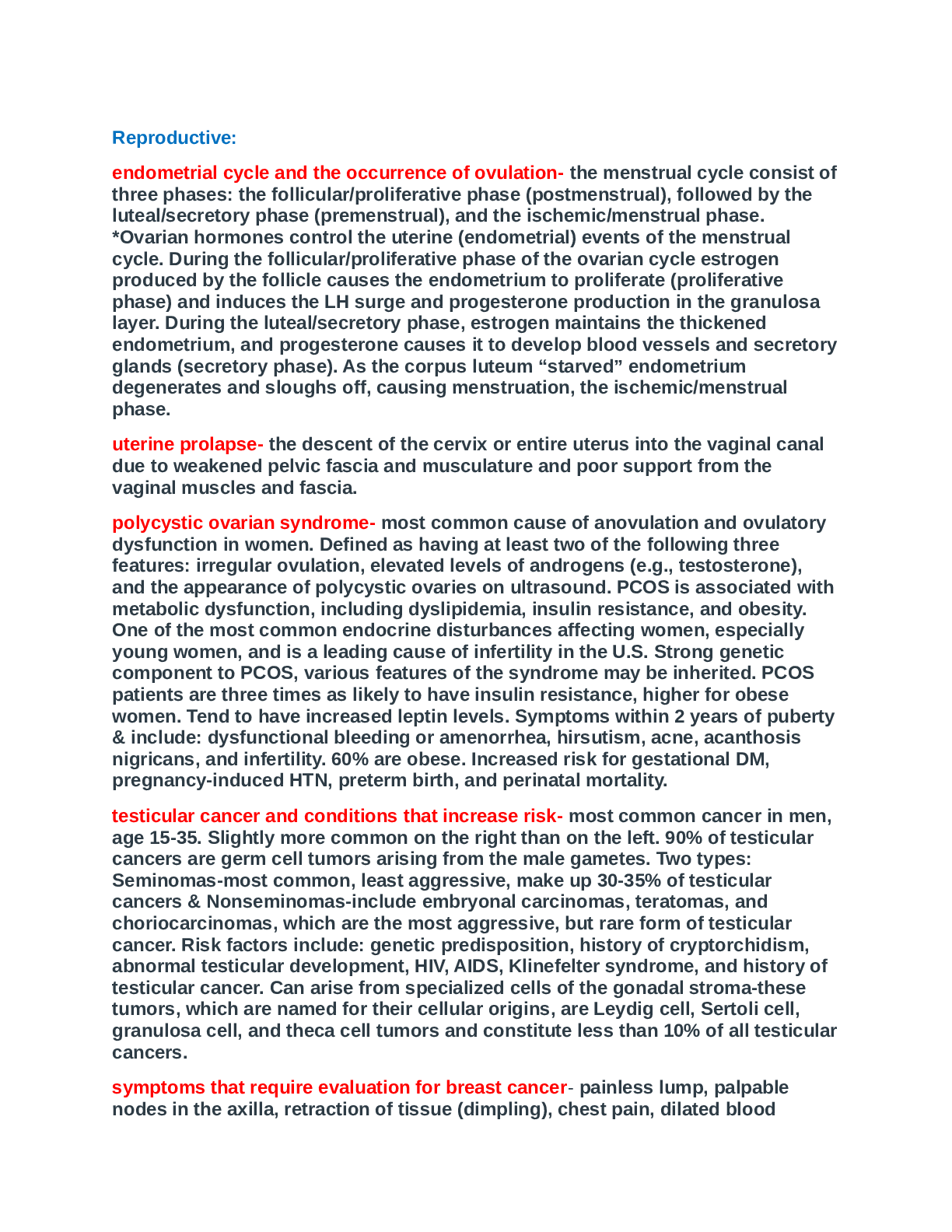

Menstrual cycle physiology

The initiation of menstruation, called menarche, usually happens between the ages of 12 and 15. Menstrual cycles typically continue to age 45 to 55, when menopause occurs. Many women find themselves reluctant to discuss the existence and normality of menstruation. The word menstruation has been replaced by a variety of euphemisms, such as the curse, my period, my monthly, my friend, the red flag, or on the rag.

Most women experience deviations from the average menstrual cycle during their reproductive years. As a result, it is not uncommon for women to display certain preoccupations regarding their menstrual bleeding, not only in relation to the regularity of its occurrence, but also in regard to the characteristics of the flow, such as volume, duration, and associated signs and symptoms. Unfortunately, society has encouraged the notion that a woman’s normalcy is based on her ability to bear children. This misperception has understandably forced women to worry over the most miniscule changes in their menstrual cycles. Indeed, changes in menstruation are one of the most frequent reasons why women visit their clinician.

Numerous patterns in the secretion of estrogens and progesterone are possible; in fact, it is difficult to find two cycles that are exactly the same. Studies that include women of different ethnicities, occupations, genetics, nutritional status, and age have demonstrated that the length and duration of the menstrual cycle vary widely (Assadi, 2013; Johnson et al., 2013; Karapanou & Papadimitriou, 2010).

Menarche is the most readily evident external event that indicates the end of one developmental stage and the beginning of a new one. It is now believed that body composition is critically important in determining the onset of puberty and menstruation in young women (Ferin & Lobo, 2012). The ratio of total body weight to lean body weight is probably the most relevant factor, and individuals who are moderately obese (i.e., 20–30% above their ideal body weight) tend to have an earlier onset of menarche (Johnson et al., 2013). Widely accepted standards for distinguishing what are regular versus irregular menses, or normal versus abnormal menses, are generally based on what is considered average and not necessarily typical for every woman.

According to these standards, the normal menstrual cycle is 21 to 35 days with a menstrual flow lasting 4 to 6 days, although a flow for as few as 2 days or as many as 8 days is still considered normal (Ferin & Lobo, 2012).

The amount of menstrual flow varies, with the average being 50 mL; nevertheless, this volume may be as little as 20 mL or as much as 80 mL. Generally, women are not aware that anovulatory cycles and abnormal uterine bleeding (changes in bleeding

outside of normal; see Chapter 24) are common after menarche and just prior to menopause (Ferin & Lobo, 2012; Fritz & Speroff, 2011). Menstrual cycles that occur during the first 1 to 1.5 years after menarche are frequently irregular due to the immaturity of the hypothalamic–pituitary–ovarian axis (Fritz & Speroff, 2011).

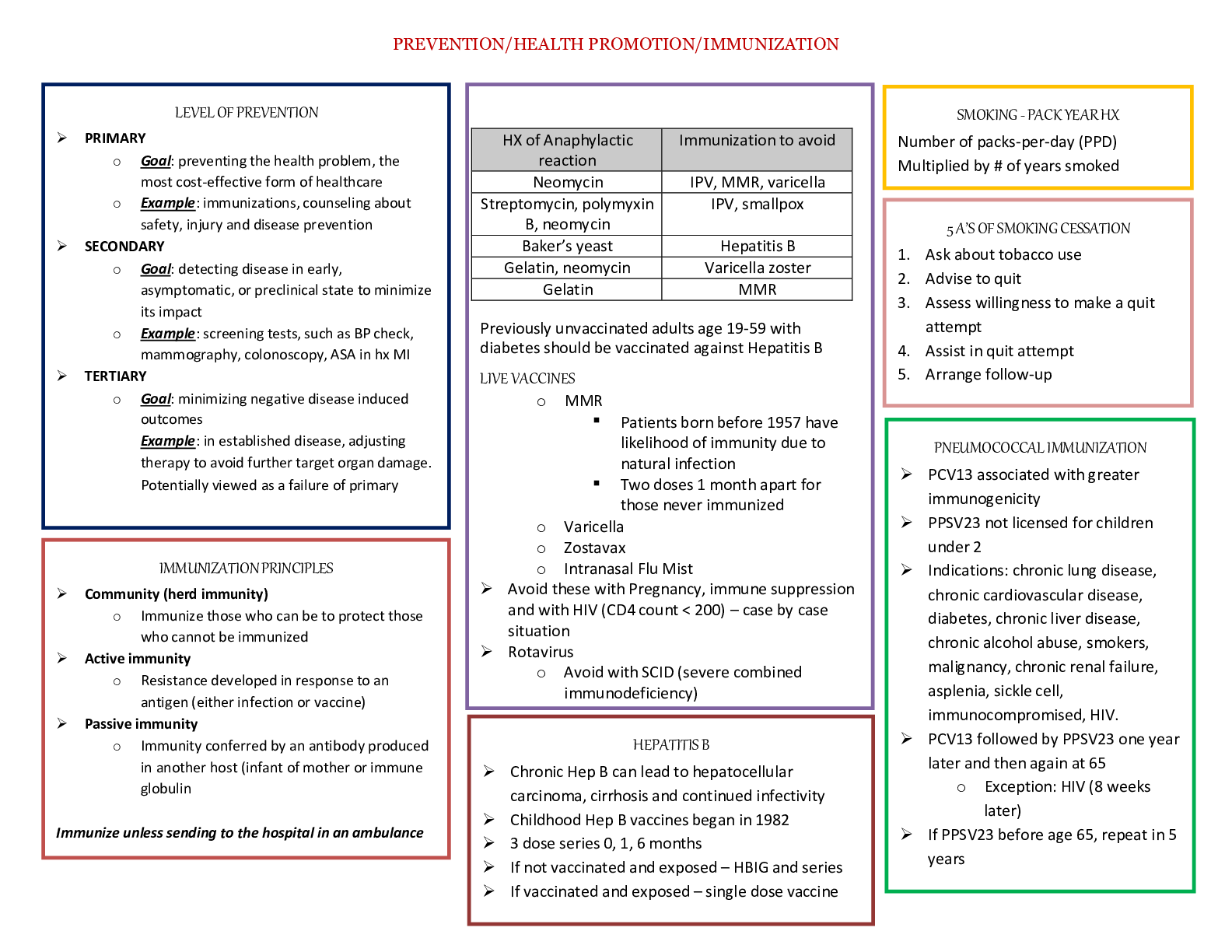

Vaccines during pregnancy

• Live vaccines are contraindicated during pregnancy (MMR, Oral Polio, Varicella & FluMist)

• Injectable influenza vaccine is an inactivated virus and is safe to use in pregnancy

Ask if the woman has ever known anyone with tuberculosis or traveled to areas where tuberculosis is common. If she is at risk, she should receive a tuberculin skin test when she can return in 48 to 72 hours. Past history of varicella is important, as well as the woman’s vaccine history, to determine if she is at risk for chickenpox.

Women can receive vaccines in pregnancy (Table 30-1). The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) updates the adult vaccine schedule often, and this information can be easily accessed on its website. The CDC website also includes detailed information about safety of vaccines for travel of local disease outbreaks during pregnancy (CDC, 2014). All women who are pregnant should be offered the influenza vaccine during flu season, though live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV [FluMist]) should not be given to pregnant women. All women should be encouraged to receive a tetanus, diphtheria, and acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccination in the third trimester (CDC, 2016). Other vaccines, such as hepatitis B, can be administered if the woman is at risk (CDC, 2016).

During pregnancy, women have a decreased immune response to pathogens, making them more susceptible to infection. If a woman has cats, she should be careful to avoid contracting toxoplasmosis—an infection that is spread through cat feces. Someone else should change the cat litter box daily to prevent contact with the Toxoplasma

gondii parasite. Wearing gloves while gardening, and careful hand washing are also essential. More information and patient handouts are available for free at the CDC website.

TABLE 30-1 Vaccines in Pregnancy

Recommended Each Preg nancy Rationale Timing

Influenza (flu)a

Women who are pregnant are at Any

increased risk for flu-related gestation

complications. when the

injection is

available

Tetanus, diphtheria, pertussis (Tdap) After maternal vaccination, antibodies cross the placenta and decrease the risk of pertussis infection in the newborn. Third trimester (ideally 27–

36 weeks’ gestation)

Advised If at Risk Rationale Timing

Hepatitis B If the woman is at risk for acquiring HBV, she should be vaccinated. Indications include risk of occupational exposure to blood, treatment for a sexually transmitted infection, more than 1 sex partner in the past 6 months, recent intravenous drug use, and HBsAg– positive sex partner. 3 injections beginning at any point in gestation

Contraindicated Rationale

Measles, mumps, rubella This live virus vaccine has a (theoretical) risk to the fetus.

Varicella This live virus vaccine has a (theoretical) risk to the fetus.

Abbreviations: HBsAg, HBV surface antigen; HBV, hepatitis B virus.

a Live attenuated influenza vaccine (LAIV [FluMist]) should not be given to pregnant women.

Emergency contraception

Sperm can live for up to 5 days in the female reproductive tract, and pregnancy can occur with intercourse 5 days prior to ovulation. The highest risk of pregnancy is in the 48 hours immediately preceding ovulation (Wilcox, Dunson, & Baird, 2000).

However, due to the uncertainty of ovulation timing, emergency contraception is offered if unprotected intercourse (UPI) occurs at any time in the menstrual cycle.

The Yuzpe, levonorgestrel, and ulipristal acetate emergency contraceptive pill (ECP) regimens as well as the copper IUD may all be used within 120 hours of UPI. The Yuzpe and levonorgestrel methods have a dramatic decline in their effectiveness with time and should be used as soon as possible after an event of UPI.

The Yuzpe regimen consists of combined ECPs that

The Yuzpe regimen consists of combined ECPs that must contain at least 100 mcg of ethinyl estradiol and 0.50 mg of levonorgestrel, repeated in 12 hours. A dedicated combined ECP product is not available in the United States, but numerous COCs can be used as combined ECPs (see Table 11-1, footnote i). COCs containing norgestrel

are preferable to those with norethindrone, as failure rates are slightly higher with norethindrone (Zieman et al., 2015). Because the high dose of ethinyl estradiol causes unpleasant side effects, this regimen has largely fallen out of favor.

Until recently, the most widely used emergency contraception method was levonorgestrel ECPs, which contain either a 1.5-mg single dose (Plan B One-Step) or two doses of 0.75 mg taken 12 hours apart (Next Choice and Plan B). Women can take both doses in the two-dose products (Next Choice and Plan B) as a single dose.

Levonorgestrel ECPs are available over the counter to women and men age 17 and older; women 16 and younger need a prescription to obtain them. Levonorgestrel ECPs are more effective than the Yuzpe regimen and have fewer side effects.

Ulipristal acetate (ella), a selective progesterone receptor modulator provided as a single 30-mg dose, is the most effective oral emergency contraception method. The effectiveness of this medication does not decline within the 120-hour window after UPI, as is the case for levonorgestrel and combined ECPs (Fine et al., 2010). Ulipristal acetate is available only by prescription.

The copper IUD can be inserted as long as 5 days after unprotected intercourse. Some contraceptive guidelines recommend its use up to 7 days after UPI (Dunn et al., 2013). This method is rarely utilized as emergency contraception in the United States; however, recent evidence suggests some women might choose the copper IUD if it is offered as an option (Turok et al., 2011). It has the advantage of being highly effective in obese women and providing ongoing contraception.

Efficacy and Effectiveness

Factors influencing the risk of pregnancy when ulipristal acetate or levonorgestrel is used

for emergency contraception include body mass index (BMI), the day of the cycle, and further intercourse during the same menstrual cycle after use of emergency contraception (Glasier et al., 2011).

Women with a BMI greater than 30 have a 2- to 40-fold higher risk of pregnancy after ECP use. Levonorgestrel may be completely ineffective at reducing pregnancy risk in obese women. The efficacy of levonorgestrel and ulipristal acetate further vary according to the stage of the cycle.

Levonorgestrel and ulipristal acetate inhibit ovulation in 96% and 100% of cycles, respectively, when used prior to the onset of the LH surge (Brache, Cochon, Deniaud, & Croxatto, 2013). However, if given after the onset of the LH surge, these medications inhibit ovulation in 14% and 79% of cycles, respectively (Glasier, 2013). Levonorgestrel is no more effective than placebo when used in the critical 5 days preceding ovulation. The risk of pregnancy with ulipristal acetate use is half that seen with use of levonorgestrel (Glasier, 2014).

Both levonorgestrel and ulipristal acetate delay ovulation. If women have repeated acts of UPI after using ECPs, they are at a 4-fold increased risk of pregnancy compared with women who do not have further intercourse within the same cycle.

The copper IUD is by far the most effective of emergency contraception methods, with a pregnancy rate of approximately 1 in 1,000 cases in which it is used for this purpose (Cheng, Che, & Gulmezoglu, 2012).

Safety and Side Effects

Levonorgestrel ECPs, combined ECPs, and ulipristal acetate should not be given to women with a known or suspected pregnancy; there are no other contraindications to their use. The long history of use of levonorgestrel indicates little risk exists if it is inadvertently taken in early pregnancy. There is less experience with ulipristal acetate, although no reasons for concern were raised in the clinical trials. The usual contraindications and precautions for ongoing COC and POP use do not apply to ECPs (CDC, 2010), but the usual contraindications and precautions to copper IUD use do apply when using this method for emergency contraception

(see Appendix 11-A). Neither the copper IUD nor oral emergency contraception methods are considered abortifacients (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2014b).

Combined ECPs frequently cause nausea and vomiting, which can be reduced by giving an antiemetic, such as promethazine, prior to treatment. Spotting, changes in next menses, headache, breast tenderness, and mood changes can also occur. These same side effects are sometimes noted with levonorgestrel ECPs but are much less frequent and less severe with this option (Zieman et al., 2015). Headache, dysmenorrhea, nausea, and abdominal pain are the most frequently observed side effects with ulipristal acetate (Fine et al.,

2010; Glasier et al., 2010). The copper IUD can cause the side effects discussed in the section on intrauterine contraception.

Advantages and Disadvantages

Emergency contraception is the only contraceptive method that can be used after intercourse. It cannot be used as an ongoing method of contraception, however, and it provides no STI protection. Access to emergency contraception remains limited because only one method— levonorgestrel ECPs—is available without prescription—and even then it is available only to women 17 and older. Clinicians can increase access to emergency contraception by providing advance prescriptions to all women of reproductive age for ulipristal acetate. Studies have shown that having ECPs at home increases the likelihood that they will be used when needed and does not promote sexual risk taking (Glasier & Baird, 1998; Raine, Harper, Leon, & Darney, 2000). Providing emergency contraception prescriptions over the phone as needed is another way to increase access.

Tier 1, 2 & 3 methods of contraception and efficacy

Tier 1

Intrauterine Devices (IUD)

• Paragard® and T380A® are copper bearing IUDs (Cu-IUD) and are effective up to 10 years

• Mirena®, Skyla® and Liletta® are IUDs that contain levonorgestrel. They are also referred to as LNG-IUSs (levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system); slightly more effective than Cu-IUDs; Mirena® is effective for up to 5 years, Skyla® and Liletta® for

up to 3 years; increases cervical mucus to make sperm penetration more difficult

• Works because the device is recognized as a foreign body and a sterile inflammatory response is produced. The inflammatory response has spermicidal

effects decreasing the likelihood of pregnancy (for both LNG-IUSs and Cu-IUD); LNG- IUSs also release progestin making them slightly more effective

• Benefits: highly effective, removes the factor of user consistency and error, long acting and reversible, reduces menstrual flow

• Contraindications: Active pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) or within the last year, suspected or confirmed pregnancy, STD, uterine or cervical abnormality, undiagnosed vaginal bleeding, cancer or history of ectopic pregnancy

• Risks: Endometrial and pelvic infections (first few months after insertion), uterine perforation, heavy or prolonged menstrual periods

• Disadvantages: Requires provider training for insertion, high initial cost

• Side Effects: bleeding and dysmenorrhea are most common, increased bleeding noted more with Cu-IUD; amenorrhea often develops

• Educate woman to check for IUD strings to ensure the device is still in place; expulsion rate is fairly low but occurs most within the first 3 months after insertion

Depot Medroxyprogesterone Acetate (DMPA)

• Depo-Provera® (progestin only); given via injection; lasts 3 months

• Prevent LH surge which inhibits ovulation, thickens cervical mucus and causes the endometrium to atrophy which reduces the likelihood of implantation; minimal

effects on coagulation, blood pressure and lipid levels

• Benefits: Highly effective; reduces menstrual flow and within a year most women have amenorrhea

• Contraindications: Suspected or confirmed pregnancy, known or suspected malignancy of the breast, significant liver disease undiagnosed vaginal bleeding,

history of anorexia, active thrombophlebitis, or current or past history of thromboembolic disorders or cerebrovascular disease

• Risks: Loss of bone mineral density (black box warning: avoid use for more than 2 years), delayed return of fertility

• Side Effects: Headache, depression, breakthrough bleeding and weight gain

• Educate woman calcium with vitamin D and weight bearing exercise to prevent bone mineral loss

• Benefits: Safe for breastfeeding women, considered safer for women who have contraindications to estrogens

• MUST check for pregnancy before starting; Disadvantages: Requires pregnancy testing if the patient does not return every 12 weeks

• Give ONLY within the 1st 5 days of a normal menstrual period-less likely to ovulate during these times

Progestin Implants

Used with permission of Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, all rights reserved.

• Nexplanon® is a single rod etonogestrel subcutaneous implant, an active metabolite of desogestrel which is effective up to 3 years

• Norplant II® has 2 rods and is effective up to 5 years

• Slow release of progestin to suppress ovulation by inhibiting LH surge

• Benefits: highly effective, removes the factor of user consistency and error, long- acting and reversible, reduces menstrual flow and decreases dysmenorrhea symptoms

• Contraindications: Suspected or confirmed pregnancy, undiagnosed vaginal bleeding, known or suspected malignancy of the breast, significant liver disease, active thrombophlebitis, or current or past history of thromboembolic disorders or

cerebrovascular disease

• Risks: Procedural associated risks are very low; insertion site bruising possible

• Disadvantages: Requires provider training for insertion, high initial cost

• Side Effects: Similar to other progestin-only methods (breakthrough bleeding, amenorrhea, breast tenderness, weight gain)

Sterilization (Tubal ligation or Vasectomy)

• Tubal ligation: Surgical procedure to block the fallopian tubes; various methods of mechanical occlusion which are generally effective immediately; Essure® is the only

transcervical method that can be performed in an office setting by hysteroscopy; Essure ® requires a hysterosalpingogram (HSG) to be done 3 months after the procedure to confirm tubal occlusion; decreased risk of ovarian cancer

• Vasectomy: Surgical procedure to occlude the vas deferens; various methods of occlusion; vasectomy is less invasive than female sterilization; not immediately

effective - the man must wait 3 months before relying on sterilization; usually advised to perform a sperm count before stopping other contraceptive methods

Tier 2 methods essentially include hormonal contraception other than LNG-IUSs and implanted devices. These include:

• Combined oral contraceptive (COC) pills- estrogen and progesterone

• Oral contraceptive pill- progestin only "Minipill"

• Emergency contraception

• Transdermal patch

• Ring

Oral Contraceptive Pills

Since you have already covered the oral contraceptive pills in pharmacology you should be well versed in the mechanism of action, contraindications, risks, benefits and adverse reactions associated with their use. Additionally, your book provides a good deal of information that is useful as a review so we will not spend much time discussing these methods. However, we will circle back to briefly discuss some important take- away information that will be beneficial to you as a provider in determining how to adjust the medication based on the patient's symptoms. Before we do that, let's talk about the patches and rings.

Transdermal

Combined Contraceptive Patch

• Ortho Evra® and Xulane®

• Provides a slow release estrogen & progesterone via the skin; new patch is applied each week for 3 weeks with a patch free time during week 4 (withdrawal period

expected during hormone free time)

• Benefits: Effective, does not require daily dosing, decreased risk of PID and ectopic pregnancies, decreased risk of ovarian and endometrial cancer, improves dysfunctional uterine bleeding (DUB) and dysmenorrhea and improves acne

• Start on 1st day of period or 1st Sunday after period; requires back-up method for 1 week

• Disadvantages: Must remember to change patch the same day every week and remove for 1 week, less effective in women over 200 lbs.

• Contraindications: Same as COC pills

• Risks: Same as COC pills

• Side effects: Same as COC pills

Cervical Ring

• NuvaRing®

• Plastic cervical ring that is placed inside the vagina for 3 weeks which provides a slow release of estrogen and progesterone; removed for 1 week at which time a withdrawal bleed should occur

• Benefits: Effective, does not require daily administration, decreased risk of PID and ectopic pregnancies, decreased risk of ovarian and endometrial cancer, improves dysfunctional uterine bleeding (DUB) and dysmenorrhea and improves acne

• Disadvantages: Woman must be educated on how to apply and remove ring (should fit snugly around the cervix), may be noticeable by patient or partner during

intercourse, not good for woman who is not comfortable with insertion and removal; can be removed prior to intercourse but should be replaced within 3 hours

• Contraindications: Same as COC pills

• Risks: Same as COC pills

• Side effects: Same as COC pills

Tier 3 methods include all of your barrier methods, natural family planning and coitus interruptus. These methods are the least effective in terms of preventing pregnancy with variable rates between them which are outlined in your textbook. The biggest advantage that the barrier methods offer in addition to preventing pregnancy is that they offer protection in preventing STDs.

Etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of amenorrhea

Amenorrhea simply means absence of menses and is part of the spectrum of ovulatory disorders classified as AUB-O. The most common causes of amenorrhea are pregnancy, hypothalamic amenorrhea, and PCOS (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2014). According to Fritz and Speroff (2011, p. 436), women meeting any of the following criteria should be evaluated for amenorrhea:

No menses by age 14 in the absence of growth or development of secondary sexual characteristics

No menses by age 16 regardless of the presence of normal growth and development of secondary sexual characteristics

In women who have menstruated previously, no menses for an interval of time equivalent to a total of at least three previous cycles, or 6 months

Amenorrhea typically is categorized as either primary or secondary. Primary amenorrhea is the failure to begin menses by the age of 16. A number of disorders can be treated as soon as they are diagnosed, however, so any girl who has not reached menarche by age 15 years or who has not had a menses within 3 years of thelarche should be evaluated (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2014).

Secondary amenorrhea is defined as 3 months without a menses once menses has been established. The American Society for Reproductive Medicine recommends that any woman experiencing 3 months of amenorrhea once the menses is established should be evaluated (American College of Obstetricians and

Gynecologists, 2014). Because primary and secondary amenorrhea can have the same causes, the initial investigation for both is similar.

Physiologic causes of amenorrhea include anatomic defects, ovarian failure, chronic anovulation, anterior pituitary disorders, and central nervous system disorders. Age is an important criterion in making the differential diagnosis of primary versus secondary amenorrhea, and is relevant in determining the types of questions to ask when taking the medical history. Primary amenorrhea in a young woman may be indicative of HPOA disorder or anatomic factors, such as outflow tract obstruction. With primary amenorrhea, the physical examination should focus on identifying the maturation of secondary sex characteristics (e.g., Tanner staging for breast development and pubic hair pattern; see Chapter 2) and establishing outflow tract patency. The question “Have you had any bleeding from the vagina?” can assist in determining primary, secondary, and potential causes. Other important interview questions to consider relate to lifestyle patterns (e.g., exercise, medication, and drug use) and eating habits (e.g., possible eating disorders). A family history of anatomic or genetic abnormalities should be explored as well.

Normal menstrual function requires that four anatomic and structural components are in working order: uterus, ovary, pituitary, and hypothalamus (Fritz & Speroff, 2011). The clinician can then categorize the amenorrhea according to the site or level of disturbance (Fritz & Speroff, p. 438):

Disorders of the genital outflow tract

Disorders of the ovary

Disorders of the anterior pituitary

Disorders of the hypothalamus or central nervous system

The differential diagnosis for women who are not pregnant and who present with amenorrhea is either primary amenorrhea or secondary amenorrhea, although Fritz and Speroff (2011) warn that premature categorization of amenorrhea can lead to diagnostic omissions and, in many cases, unnecessary and expensive diagnostic testing.

Athletic women, particularly long-distance runners, gymnasts, and professional ballet dancers, are at risk for amenorrhea, as are women who have anorexia and other eating disorders (Fritz & Speroff, 2011;

Polotsky, 2010). Typically, amenorrhea occurs as the menstrual cycle stops after the start of an intensive training regimen, although some reports indicate that when intensive training begins prior to menarche, menarche can be delayed by as much as 3 years (Fritz & Speroff, 2011). It is important to understand that it is not exercise in general that causes the amenorrhea, but rather the specific type of exercise (Fritz & Speroff, 2011). For example, swimming is less likely to cause amenorrhea than long-distance running.

Women with a low BMI and low percentage of body fat combined with a high level of intensive physical activity have the highest risk for amenorrhea (Fritz & Speroff, 2011).

The pathophysiology of exercise-induced amenorrhea is complex and most likely due to the combination of low body fat and diminished secretion of GnRH. Lower GnRH levels result in fewer luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) pulses, which in turn decreases the amount of estrogen produced by the ovaries. The critical weight theory hypothesizes that some critical weight and amount of body fat exist that must be maintained for women to experience regular menstrual cycles (Fritz & Speroff, 2011).

Treat= All women with anovulation require management of this condition: If left untreated, endometrial cancer can occur, regardless of the woman’s age. Typically treatment consists of inducing menses using a progestogen such as medroxyprogesterone acetate 5 to 10 mg daily for the first 12 to 14 days of the cycle. It is important for the woman to know she is not protected against pregnancy during this treatment. If she does not have her menses, she should have a pregnancy test if she has engaged in intercourse during the treatment period. Oral contraceptive pills can also be used to induce a menstrual cycle.

Etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of dysmenorrhea (primary vs. secondary)

One of the most common gynecologic complaints that you will encounter in primary care is dysmenorrhea. Dysmenorrhea refers to painful uterine contractions which occur during menstruation and is one of the most common causes of chronic pelvic pain in women of reproductive ages. It is characterized as cyclical (occurring before or during menses) pain that results from an excessive amount of endometrial prostaglandin production. Prostaglandins stimulate the uterine myometrium which induce uterine irritability and contractions thereby resulting in pain and cramping. Other common symptoms may accompany dysmenorrhea and are associated with premenstrual syndrome (PMS) and premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD), which we will discuss more in a separate section.

Many women experience mild discomfort during menstruation, but the term dysmenorrhea is reserved for women whose pain prevents or interferes with normal activity and requires medication (OTC or prescription). In some women, the pain of dysmenorrhea can be significant and disruptive to school, work and social activities. It is also underreported and undertreated due, largely in part, to negative social and gender stigmas associated with menstruation. In some third world countries, women are still banished from their homes and forced to live in “menstrual huts” during their periods and are without basic hygiene needs. You may even be aware of some of the global efforts to promote health education in order to ameliorate the myths associated with menstruation as well as measures to improve access to sanitary hygiene products.

Primary dysmenorrhea, which is more common than secondary dysmenorrhea, often begins 6 to 12 months after menarche. Typically symptoms are experienced with the onset of bleeding and continue for 8 to 72 hours into the menstrual cycle. Increased endometrial prostaglandin production is believed to be the cause of the associated pain (Lentz, 2007). It is associated with multiple symptoms, including abdominal cramps, headache, backache, general body aches, continuous abdominal pain, and other somatic discomforts. The difference between

primary dysmenorrhea and normal somatic and psychological changes prior to menses is that primary dysmenorrhea is perceived as more severe, with chronic, sometimes debilitating symptoms. There is no evidence of organic pathology in the uterus, fallopian tubes, or ovaries with primary dysmenorrhea. Women usually report repeated symptomology with each cycle. When charting their cycles, it is evident that that pain, bleeding, and disruption of lifestyle occur at regular times in the cycle.

Dysmenorrhea can be classified into 2 categories:

1. Primary-Cyclical menstrual pain with no identifiable pelvic disease

2. Secondary-Cyclical menstrual pain that results from pelvic pathology

Primary dysmenorrhea is almost always associated with ovulatory cycles so it usually does not occur immediately at menarche, but rather within the first 6 months.

Typically the age of onset is between 16-25 years and becomes more severe with age.

Associated primary dysmenorrhea is a diagnosis of EXCLUSION, in other words, secondary causes must be ruled out before rendering the diagnosis.

Primary dysmenorrhea is likely based on history as well as an unremarkable physical exam and a negative pregnancy test.

The most common MISDIAGNOSIS of primary dysmenorrhea is secondary dysmenorrhea due to endometriosis.

Dysmenorrhea that is caused by pelvic pathology is referred to as secondary dysmenorrhea.

Diagnosis of secondary dysmenorrhea includes pelvic pathology such as adenomyosis, leiomyomata, irritable bowel syndrome, interstitial cystitis, and endometriosis (Hoffman, 2008). Almost any process that can affect the pelvic viscera and cause acute or intermittent recurring pain might be a source of cyclic premenstrual pain, including urinary tract infection, pelvic inflammatory disease, hernia, and pelvic relaxation or prolapse

Secondary dysmenorrhea is pain due to an underlying pelvic pathology which may include, but is not limited to: pelvic inflammatory disease, endometriosis, uterine fibroids and adenomyosis.

However, almost any pathology that causes irritation to the pelvic viscera may be a source of pain including bladder and bowel disorders.

Endometriosis is the MOST common cause of secondary dysmenorrhea.

Endometriosis, the most common cause of secondary dysmenorrhea, is a growth or multiple growths (polyps) of endometrial tissue that are found outside of the uterine cavity.

Because the lesions are uterine tissue, they respond to the cyclic hormones of the menstrual cycle which result in bleeding and pain.

The lesions can also attach to adjacent organs such as the ovaries, bowel, bladder or peritoneum.

Uterine fibroids are benign tumors of the uterine myometrium, the smooth muscle of the uterus. Fibroids can range in size from microscopic to very large. Single or multiple fibroids are possible.

Like endometriosis, fibroids can be associated with menorrhagia, infertility and bowel and bladder complaints. Uterine fibroids are the most common indication for hysterectomy in the United States.

Risk factors include heredity, obesity, african american ancestry and a primiparous status (giving birth to only 1 child).

Differentiate between PMS & PMDD.

Symptoms PMS PMDD

Physical Abdominal bloating and Physical: same as PMS but may be more severe

symptoms pain Symptoms can begin immediately after ovulation

Mild weight gain from water Abdominal bloating and pain

retention Headache

Constipation followed by Pelvic pain and cramping

diarrhea at the onset of the Fatigue

menses Extremity edema

Headache Nausea/food cravings

Pelvic pain and cramping

Fatigue

Extremity edema

Nausea/food cravings

Psychologic Depression Marked affective lability

symptoms Anxiety Marked irritability or anger or increased

Anger/irritability interpersonal conflicts

Insomnia Markedly depressed mood, feelings of

Changes in libido hopelessness, or self-deprecating thoughts

Symptoms

PMS

PMDD

Confusion, decrease in mental sharpness Social withdrawal Feelings of low self- esteem/poor self-image

Marked anxiety, tension, feelings of being “keyed up” or “on edge”

Decreased interest in usual activities Subjective sense of difficulty concentrating Lethargy

Insomnia or hypersomnia

A subjective sense of being overwhelmed or out of control

Diagnostic criteria

Symptoms begin up to 7 days prior to menses Remission of symptoms occurs from cycle days 4– 13

Symptoms are significant enough to impair activities of daily living

Symptoms are charted in at least 2 cycles

Symptoms are not due to another disorder

Symptoms are associated with clinically significant distress or interference with work, school, social activities, or relationships with others

The disturbance is not an exacerbation of the symptoms of another disorder (e.g., major depressive disorder)

Criteria should be confirmed by prospective daily ratings during at least 2 symptomatic cycles (the diagnosis may be made provisionally prior to this confirmation)

Symptoms are not due to the direct physiological effects of a substance (e.g., drug abuse, medications other than treatment) or a general medical condition

Abbreviations: PMDD, premenstrual dysphoric disorder; PMS, premenstrual syndrome.

PMS can be defined as a cluster of mild to moderate physical and psychological symptoms that occur during the late luteal phase of menses and resolve with menstruation (Baller et al., 2013; Biggs & DeMuth, 2011). PMDD encompasses cognitive, behavioral, emotional, and negative symptomatic changes that severely impair daily functioning, relationships, parenting, and ability to work in the late luteal menstrual phase

PMS) describes the cyclical recurrence of symptoms that impair a woman’s health, relationships, and occupational functioning. Premenstrual dysphoric disorder (PMDD) is a diagnostic label that applies to a much smaller number of menstruating women experiencing severe PMS with predominantly negative affective symptoms.

Premenstrual Syndrome (PMS) and Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder (PMDD) are conditions which have both physical and behavioral symptoms that occur during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle. PMS is common and occurs in the majority of premenopausal women, whereby one or more affective or somatic symptoms occur; PMDD has a far less common incidence. PMDD is considered a more severe form of PMS, where the symptoms significantly disrupt daily functioning. Etiologies are not well understood but evidence that diet, hormones, behavioral and psychosocial factors may all contribute to the development of PMS and PMDD in some way. The treatment of PMS/PMDD depends on the severity of the symptoms. Mild symptoms can be treated with dietary changes (limiting caffeine, alcohol and tobacco or eating

regular small high carbohydrate meals). Exercise, stress management, NSAIDs, vitamin supplements and cognitive behavioral therapies may also be helpful.

Treatment for moderate or severe symptoms include a SSRI (fluoxetine, sertraline, paroxetine, etc.) which can be given continuously or during the luteal phase only, or combined oral contraceptives given continuously or with reduced non-hormone days. GnRH agonist may be also be tried if symptom relief is not achieved with the other medical treatment options. Bilateral oophorectomy and hysterectomy are reserved for refractory cases of moderate to severe PMDD.

Abnormal uterine bleeding terminology

Abnormal Uterine Bleeding (AUB) is a term used to refer to uterine bleeding that is atypical in the frequency, regularity, duration and timing and is a common gynecological disorder. "Normal" menstruation can be classified into the following parameters:

Frequency Every 24-38 days

Regularity +/- 2-20 days

Duration 3-8 days

Quantity 5-80 mL (roughly 3-6 pads per day)

AUB occurs in various “patterns” which are important to first understand before we discuss etiologies.

Structural vs. Nonstructural etiologies of abnormal uterine bleeding

Evaluation and management of abnormal uterine bleeding

History

Obtaining a thorough gynecological history is essential in order to help establish the differential diagnosis for ANY menstrual disorder including AUB. A thorough history should include:

• Age

• Overall health & lifestyle

• Chronic diseases, history of trauma, extreme stressors, exercise regularity (i.e., competitive)

• History of personal or family eating disorders

• Family history of reproductive disorders

• Changes in body weight or in body distribution

• Age at menarche

• Parity

• Menstrual history (regularity, frequency, durations, volume)

• Dysmenorrhea, post-coital bleeding, dyspareunia, infertility, vaginal discharge

• Recent abortion

• Sexual activity

• Contraception (IUD, OCP, hormones)

• Medications

• Symptoms of endocrine disorders (heat intolerance, headaches, weight gain or loss, hair loss, dry skin, increase in shoe or breast size, galactorrhea, etc)

• Symptoms of bleeding disorders (easy bruising, petechiae, etc.)

Physical Examination

• Height, weight, body fat distribution and BMI

• Vital signs (pulse, blood pressure, respiratory rate)

• Color of skin and capillary refill (pallor is suggestive of anemia due to heavy menstrual bleeding)

• Thyroid examination (nodules or goiter)

• Assess for androgen excess (hirsutism, acanthosis nigricans, acne, alopecia)

• Breast exam is warranted if the patient reports breast changes or nipple discharge

• A visual field examination should also be performed in any patient with headaches or galactorrhea (suggestive of pituitary adenoma)

Pelvic Examination

A pelvic exam should be performed on any woman who is or has been sexually active and has irregular or heavy bleeding.

• Visual inspection of the external genitalia (may reveal signs of androgen excess, trauma, or vaginal atrophy due to lack of estrogen)

• A speculum examination should be performed to assess the vagina for foreign bodies, evidence of infection or trauma, as well as to assess the cervix for signs of abnormal growths, lesions or infection

• A bimanual examination should be performed to assess the size and position of the uterus, presence of palpable masses, uterine tenderness and adnexal masses or

tenderness

Diagnostic Studies

Testing decisions should be based on the differential diagnosis that is derived from the patient's history and physical. There are MANY tests and procedures that are available but not all should be performed. Generally speaking, perform the least invasive tests to narrow your differential and start with the most likely causes first. Table 24-4 in your

textbook provides an excellent guide to ordering tests according to the condition that you are trying to rule out. Laboratory tests should be ordered selectively and must always include the patient in the testing and management plan. Tests that may be considered include:

• Pregnancy test (qualitative vs. quantitative; asses for pregnancy or threatened abortion)

• CBC with differential (assess for anemia or clotting disorder)

• PT, aPTT (assess for bleeding disorder)

• Serum ferritin (assess for iron deficiency; only necessary IF anemia is present)

• TSH with reflex FT4 (assess for thyroid dysfunction)

• Prolactin (assess for prolactinoma/pituitary adenoma)

• FSH (assess for menopause or premature ovarian failure)

• Cervical cytology (assess for atypical cells suggestive of dysplasia or cancer; follow current cervical screening guidelines)

• Microscopic exam of vaginal secretion (assess for vaginal candidiasis or bacterial vaginosis)

• STI testing of vaginal secretions (gonorrhea, chlamydia, trichomoniasis)

• Ultrasonography (assess for abnormal masses)

• Endometrial sampling* (assess for endometrial hyperplasia or cancer)

• Hysteroscopy or Laparoscopy* (for biopsy and histology of an identified mass)

(*) Requires a referral to OB/GYN

Provider Tips

• Unopposed estrogen stimulation of the endometrium results in endometrial hyperplasia which increases a woman's risk of endometrial cancer. The most common symptom is post-menopausal bleeding. Therefore, providers should assume that ALL women with post-menopausal bleeding OR women ≥ 45 years with AUB have endometrial cancer UNTIL proven otherwise with endometrial biopsy

• In women of reproductive age, a complication of pregnancy must always be

considered as a cause for abnormal uterine bleeding. Therefore, all women with AUB should be considered pregnant UNTIL proven otherwise

Management and Treatment

Definitive management of AUB should focus on normalizing bleeding, correcting anemia (if present), preventing cancer and restoring quality of life for the patient. The treatment options that are available for AUB are based on the cause and may include pharmacologic measures such as contraceptives, GnRHs, NSAIDs and antifibrinolytics. Non-pharmacological interventions typically include surgical methods such as endometrial ablation, thermal endometrium destruction, uterine artery embolization and hysterectomy. Referral is indicated for an unidentified cause of AUB, complicated cases, refractory treatment, and surgery.

Breast mass types and diagnostic studies

The most common benign breast masses are fibroadenomas and cysts. Lipomas, fat necroses, phyllodes tumors, hamartomas, and galactoceles may also be encountered.

Fibroadenomas, which are composed of dense epithelial and fibroblastic tissue, are usually nontender, encapsulated, round, movable, and firm. They are the most common type of breast mass in adolescents and young women. Their incidence decreases with increasing age, but they still account for 12% of

masses in menopausal women (Pearlman & Griffin, 2010). Multiple fibroadenomas occur in 10% to 15% of cases (Vashi, Hooley, Butler, Geisel, & Philpotts, 2013). A proposed etiology for formation of these masses is the effect of estrogen on susceptible tissue (Vashi et al., 2013).

Cysts are fluid-filled masses that are most commonly found in women aged 35 to 50 years (Berg, Sechtin, Marques, & Zhang, 2010). They are thought to result from cystic lobular involution. Although many of these lesions can be dismissed as benign simple cysts requiring intervention only for symptomatic relief, complex cystic and solid masses require biopsy.

A lipoma is an area of fatty tissue that may occur in the breast or other areas of the body, including the arms, legs, and abdomen. Lipomas typically occur in the later reproductive years (Grobmeyer, Copeland, Simpson, & Page, 2009). Fat necrosis is usually the result of trauma to the breast, whether as a result of external force against the tissue (e.g., a seat belt in a motor vehicle accident) or subsequent to surgical manipulation of tissue (Grobmeyer et al., 2009)

Phyllodes tumors form from periductal stromal cells of the breast and present as a firm, palpable mass. These typically large and fast-growing masses account for fewer than 1% of all breast neoplasms.

Phyllodes tumors, which can range from a benign mass to a sarcoma, are usually seen in women aged 30 to 50 years (Pearlman & Griffin, 2010). Hamartomas are composed of glandular tissue, fat, and fibrous connective tissue; the average age at presentation for these masses is 45 years (Sevim et al., 2014).

Galactoceles are milk-filled cysts that usually occur during or after lactation. They result from duct dilation and often have an inflammatory component (Vashi et al., 2013). See Color Plate 12 for an example of a breast mass.

Type

of Mass Typical Physical Examination Findings Tissue Sampling Findings

Fibroadenoma Discrete, smooth, round or oval, nontender, mobile Ductal epithelium, dense stroma, numerous elongated nuclei without fat

Cyst Discrete, tender, mobile; size may fluctuate with the menstrual cycle Cyst fluid and inflammation

Lipoma Discrete, soft, nontender; may or may not be mobile Fatty tissue

Fat necrosis Ill defined, firm, nontender, nonmobile Necrotic fat with inflammation

Type

of Mass Typical Physical Examination Findings Tissue Sampling Findings

Phyllodes tumor Discrete, firm, round, mobile, findings similar to a fibroadenoma, but mass is usually larger; may observe stretching of skin due to rapid tumor growth Stromal hypercellularity with glandular and ductal elements

Hamartoma Discrete, nontender, nonmobile; may be nonpalpable with incidental diagnosis on imaging studies Glandular tissue, fat, and fibrous connective tissue

Galactocele Discrete, firm, sometimes tender Fat globules

If the physical examination suggests a palpable area of concern, order an ultrasound if the woman is younger than age 30, and a diagnostic mammogram with or without an ultrasound if she is 30 years or older. If the mass is suspicious for malignancy on physical examination and the woman is least 30 years of age, order a mammogram and ultrasound (NCCN, 2015a; Salzman et al., 2012). Ultrasound helps to distinguish a cystic mass from a solid mass, but is not as accurate as tissue sampling. Mammography can be used to detect nonpalpable abnormalities if a woman is of appropriate screening age or has a solid mass. Palpable breast masses may not be visible with diagnostic imaging tests, however, so these tests cannot rule out malignancy.

Biopsy is required to definitively ascertain whether a mass is solid versus cystic, and benign versus malignant. A fine-needle aspiration (FNA) biopsy is a minimally invasive way to differentiate solid and cystic masses, and provides for cytologic evaluation of a palpable mass. FNA biopsy may also be therapeutic if the mass is filled with fluid.

Tissue sample findings for benign breast masses are described in Table 15-2. If cytologic evaluation does not yield definitive findings, a more invasive method of tissue sampling (Table 15-3) is required to rule out breast cancer or determine the type of tumor if the mass is benign

Differential diagnosis for pelvic pain

Diagnoses of Gynecologic Origin Nongynecologic Diagnoses

Endometriosis

Chronic pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) Dysmenorrhea, primary and secondary Pelvic adhesions

Pelvic congestion Mittelschmerz Vulvodynia Uterine prolapse Ovarian cyst

Ovarian remnant syndrome Adenomyosis

Fibroids Ovarian cancer Cervical cancer

Torsion of adnexa Tubo-ovarian abscess Uterine fibroids Ectopic pregnancy

Abortion, threatened or incomplete

Gastrointestinal

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) Diverticulitis

Constipation Bowel obstruction Appendicitis Colon cancer Gastroenteritis

Genitourinary

• Interstitial cystitis

Urinary tract infection Urinary retention Renal calculi Pyelonephritis Ureteral lithiasis Bladder neoplasm

Musculoskeletal

• Scoliosis

Radiculopathy Arthritis Herniated disk Hernia

• Abdominal wall hematoma

Other

• Aortic aneurysm

Pelvic thrombophlebitis

• Acute porphyria

• Abdominal angina

Psychiatric, depression Somatization disorder

Prior or current physical or sexual abuse

Diagnoses of Gynecologic Origin Nongynecologic Diagnoses

Endometriosis

Chronic pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) Dysmenorrhea, primary and secondary Pelvic adhesions

Pelvic congestion Mittelschmerz Vulvodynia Uterine prolapse Ovarian cyst

Ovarian remnant syndrome Adenomyosis

Fibroids Ovarian cancer Cervical cancer

Torsion of adnexa Tubo-ovarian abscess Uterine fibroids Ectopic pregnancy

Abortion, threatened or incomplete

Gastrointestinal

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) Diverticulitis

Constipation Bowel obstruction Appendicitis Colon cancer Gastroenteritis

Genitourinary

• Interstitial cystitis

Urinary tract infection Urinary retention Renal calculi Pyelonephritis Ureteral lithiasis Bladder neoplasm

Musculoskeletal

• Scoliosis

Radiculopathy Arthritis Herniated disk Hernia

• Abdominal wall hematoma

Other

• Aortic aneurysm

Pelvic thrombophlebitis

• Acute porphyria

• Abdominal angina

Psychiatric, depression Somatization disorder

Prior or current physical or sexual abuse

Diagnoses of Gynecologic Origin Nongynecologic Diagnoses

Endometriosis

Chronic pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) Dysmenorrhea, primary and secondary Pelvic adhesions

Pelvic congestion Mittelschmerz Vulvodynia Uterine prolapse Ovarian cyst

Ovarian remnant syndrome Adenomyosis

Fibroids Ovarian cancer Cervical cancer

Torsion of adnexa Tubo-ovarian abscess Uterine fibroids Ectopic pregnancy

Abortion, threatened or incomplete

Gastrointestinal

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) Diverticulitis

Constipation Bowel obstruction Appendicitis Colon cancer Gastroenteritis

Genitourinary

• Interstitial cystitis

Urinary tract infection Urinary retention Renal calculi Pyelonephritis Ureteral lithiasis Bladder neoplasm

Musculoskeletal

• Scoliosis

Radiculopathy Arthritis Herniated disk Hernia

• Abdominal wall hematoma

Other

• Aortic aneurysm

Pelvic thrombophlebitis

• Acute porphyria

• Abdominal angina

Psychiatric, depression Somatization disorder

Prior or current physical or sexual abuse

Diagnoses of Gynecologic Origin Nongynecologic Diagnoses

Endometriosis

Chronic pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) Dysmenorrhea, primary and secondary Pelvic adhesions

Pelvic congestion Mittelschmerz Vulvodynia Uterine prolapse Ovarian cyst

Ovarian remnant syndrome Adenomyosis

Fibroids Ovarian cancer Cervical cancer

Torsion of adnexa Tubo-ovarian abscess Uterine fibroids Ectopic pregnancy

Abortion, threatened or incomplete

Gastrointestinal

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) Diverticulitis

Constipation Bowel obstruction Appendicitis Colon cancer Gastroenteritis

Genitourinary

• Interstitial cystitis

Urinary tract infection Urinary retention Renal calculi Pyelonephritis Ureteral lithiasis Bladder neoplasm

Musculoskeletal

• Scoliosis

Radiculopathy Arthritis Herniated disk Hernia

• Abdominal wall hematoma

Other

• Aortic aneurysm

Pelvic thrombophlebitis

• Acute porphyria

• Abdominal angina

Psychiatric, depression Somatization disorder

Prior or current physical or sexual abuse

Diagnoses of Gynecologic Origin Nongynecologic Diagnoses

Endometriosis

Chronic pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) Dysmenorrhea, primary and secondary Pelvic adhesions

Pelvic congestion Mittelschmerz Vulvodynia Uterine prolapse Ovarian cyst

Ovarian remnant syndrome Adenomyosis

Fibroids Ovarian cancer Cervical cancer

Torsion of adnexa Tubo-ovarian abscess Uterine fibroids Ectopic pregnancy

Abortion, threatened or incomplete

Gastrointestinal

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) Diverticulitis

Constipation Bowel obstruction Appendicitis Colon cancer Gastroenteritis

Genitourinary

• Interstitial cystitis

Urinary tract infection Urinary retention Renal calculi Pyelonephritis Ureteral lithiasis Bladder neoplasm

Musculoskeletal

• Scoliosis

Radiculopathy Arthritis Herniated disk Hernia

• Abdominal wall hematoma

Other

• Aortic aneurysm

Pelvic thrombophlebitis

• Acute porphyria

• Abdominal angina

Psychiatric, depression Somatization disorder

Prior or current physical or sexual abuse

Diagnoses of Gynecologic Origin Nongynecologic Diagnoses

Endometriosis

Chronic pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) Dysmenorrhea, primary and secondary Pelvic adhesions

Pelvic congestion Mittelschmerz Vulvodynia Uterine prolapse Ovarian cyst

Ovarian remnant syndrome Adenomyosis

Fibroids Ovarian cancer Cervical cancer

Torsion of adnexa Tubo-ovarian abscess Uterine fibroids Ectopic pregnancy

Abortion, threatened or incomplete

Gastrointestinal

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) Diverticulitis

Constipation Bowel obstruction Appendicitis Colon cancer Gastroenteritis

Genitourinary

• Interstitial cystitis

Urinary tract infection Urinary retention Renal calculi Pyelonephritis Ureteral lithiasis Bladder neoplasm

Musculoskeletal

• Scoliosis

Radiculopathy Arthritis Herniated disk Hernia

• Abdominal wall hematoma

Other

• Aortic aneurysm

Pelvic thrombophlebitis

• Acute porphyria

• Abdominal angina

Psychiatric, depression Somatization disorder

Prior or current physical or sexual abuse

Diagnoses of Gynecologic Origin Nongynecologic Diagnoses

Endometriosis

Chronic pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) Dysmenorrhea, primary and secondary Pelvic adhesions

Pelvic congestion Mittelschmerz Vulvodynia Uterine prolapse Ovarian cyst

Ovarian remnant syndrome Adenomyosis

Fibroids Ovarian cancer Cervical cancer

Torsion of adnexa Tubo-ovarian abscess Uterine fibroids Ectopic pregnancy

Abortion, threatened or incomplete

Gastrointestinal

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) Diverticulitis

Constipation Bowel obstruction Appendicitis Colon cancer Gastroenteritis

Genitourinary

• Interstitial cystitis

Urinary tract infection Urinary retention Renal calculi Pyelonephritis Ureteral lithiasis Bladder neoplasm

Musculoskeletal

• Scoliosis

Radiculopathy Arthritis Herniated disk Hernia

• Abdominal wall hematoma

Other

• Aortic aneurysm

Pelvic thrombophlebitis

• Acute porphyria

• Abdominal angina

Psychiatric, depression Somatization disorder

Prior or current physical or sexual abuse

Diagnoses of Gynecologic Origin Nongynecologic Diagnoses

Endometriosis

Chronic pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) Dysmenorrhea, primary and secondary Pelvic adhesions

Pelvic congestion Mittelschmerz Vulvodynia Uterine prolapse Ovarian cyst

Ovarian remnant syndrome Adenomyosis

Fibroids Ovarian cancer Cervical cancer

Torsion of adnexa Tubo-ovarian abscess Uterine fibroids Ectopic pregnancy

Abortion, threatened or incomplete

Gastrointestinal

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) Diverticulitis

Constipation Bowel obstruction Appendicitis Colon cancer Gastroenteritis

Genitourinary

• Interstitial cystitis

Urinary tract infection Urinary retention Renal calculi Pyelonephritis Ureteral lithiasis Bladder neoplasm

Musculoskeletal

• Scoliosis

Radiculopathy Arthritis Herniated disk Hernia

• Abdominal wall hematoma

Other

• Aortic aneurysm

Pelvic thrombophlebitis

• Acute porphyria

• Abdominal angina

Psychiatric, depression Somatization disorder

Prior or current physical or sexual abuse

Diagnoses of Gynecologic Origin Nongynecologic Diagnoses

Endometriosis

Chronic pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) Dysmenorrhea, primary and secondary Pelvic adhesions

Pelvic congestion Mittelschmerz Vulvodynia Uterine prolapse Ovarian cyst

Ovarian remnant syndrome Adenomyosis

Fibroids Ovarian cancer Cervical cancer

Torsion of adnexa Tubo-ovarian abscess Uterine fibroids Ectopic pregnancy

Abortion, threatened or incomplete

Gastrointestinal

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) Diverticulitis

Constipation Bowel obstruction Appendicitis Colon cancer Gastroenteritis

Genitourinary

• Interstitial cystitis

Urinary tract infection Urinary retention Renal calculi Pyelonephritis Ureteral lithiasis Bladder neoplasm

Musculoskeletal

• Scoliosis

Radiculopathy Arthritis Herniated disk Hernia

• Abdominal wall hematoma

Other

• Aortic aneurysm

Pelvic thrombophlebitis

• Acute porphyria

• Abdominal angina

Psychiatric, depression Somatization disorder

Prior or current physical or sexual abuse

Diagnoses of Gynecologic Origin Nongynecologic Diagnoses

Endometriosis

Chronic pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) Dysmenorrhea, primary and secondary Pelvic adhesions

Pelvic congestion Mittelschmerz Vulvodynia Uterine prolapse Ovarian cyst

Ovarian remnant syndrome Adenomyosis

Fibroids Ovarian cancer Cervical cancer

Torsion of adnexa Tubo-ovarian abscess Uterine fibroids Ectopic pregnancy

Abortion, threatened or incomplete

Gastrointestinal

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) Diverticulitis

Constipation Bowel obstruction Appendicitis Colon cancer Gastroenteritis

Genitourinary

• Interstitial cystitis

Urinary tract infection Urinary retention Renal calculi Pyelonephritis Ureteral lithiasis Bladder neoplasm

Musculoskeletal

• Scoliosis

Radiculopathy Arthritis Herniated disk Hernia

• Abdominal wall hematoma

Other

• Aortic aneurysm

Pelvic thrombophlebitis

• Acute porphyria

• Abdominal angina

Psychiatric, depression Somatization disorder

Prior or current physical or sexual abuse

Diagnoses of Gynecologic Origin Nongynecologic Diagnoses

Endometriosis

Chronic pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) Dysmenorrhea, primary and secondary Pelvic adhesions

Pelvic congestion Mittelschmerz Vulvodynia Uterine prolapse Ovarian cyst

Ovarian remnant syndrome Adenomyosis

Fibroids Ovarian cancer Cervical cancer

Torsion of adnexa Tubo-ovarian abscess Uterine fibroids Ectopic pregnancy

Abortion, threatened or incomplete

Gastrointestinal

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) Diverticulitis

Constipation Bowel obstruction Appendicitis Colon cancer Gastroenteritis

Genitourinary

• Interstitial cystitis

Urinary tract infection Urinary retention Renal calculi Pyelonephritis Ureteral lithiasis Bladder neoplasm

Musculoskeletal

• Scoliosis

Radiculopathy Arthritis Herniated disk Hernia

• Abdominal wall hematoma

Other

• Aortic aneurysm

Pelvic thrombophlebitis

• Acute porphyria

• Abdominal angina

Psychiatric, depression Somatization disorder

Prior or current physical or sexual abuse

Diagnoses of Gynecologic Origin Nongynecologic Diagnoses

Endometriosis

Chronic pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) Dysmenorrhea, primary and secondary Pelvic adhesions

Pelvic congestion Mittelschmerz Vulvodynia Uterine prolapse Ovarian cyst

Ovarian remnant syndrome Adenomyosis

Fibroids Ovarian cancer Cervical cancer

Torsion of adnexa Tubo-ovarian abscess Uterine fibroids Ectopic pregnancy

Abortion, threatened or incomplete

Gastrointestinal

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) Diverticulitis

Constipation Bowel obstruction Appendicitis Colon cancer Gastroenteritis

Genitourinary

• Interstitial cystitis

Urinary tract infection Urinary retention Renal calculi Pyelonephritis Ureteral lithiasis Bladder neoplasm

Musculoskeletal

• Scoliosis

Radiculopathy Arthritis Herniated disk Hernia

• Abdominal wall hematoma

Other

• Aortic aneurysm

Pelvic thrombophlebitis

• Acute porphyria

• Abdominal angina

Psychiatric, depression Somatization disorder

Prior or current physical or sexual abuse

Diagnoses of Gynecologic Origin Nongynecologic Diagnoses

Endometriosis

Chronic pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) Dysmenorrhea, primary and secondary Pelvic adhesions

Pelvic congestion Mittelschmerz Vulvodynia Uterine prolapse Ovarian cyst

Ovarian remnant syndrome Adenomyosis

Fibroids Ovarian cancer Cervical cancer

Torsion of adnexa Tubo-ovarian abscess Uterine fibroids Ectopic pregnancy

Abortion, threatened or incomplete

Gastrointestinal

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) Diverticulitis

Constipation Bowel obstruction Appendicitis Colon cancer Gastroenteritis

Genitourinary

• Interstitial cystitis

Urinary tract infection Urinary retention Renal calculi Pyelonephritis Ureteral lithiasis Bladder neoplasm

Musculoskeletal

• Scoliosis

Radiculopathy Arthritis Herniated disk Hernia

• Abdominal wall hematoma

Other

• Aortic aneurysm

Pelvic thrombophlebitis

• Acute porphyria

• Abdominal angina

Psychiatric, depression Somatization disorder

Prior or current physical or sexual abuse

Diagnoses of Gynecologic Origin Nongynecologic Diagnoses

Endometriosis

Chronic pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) Dysmenorrhea, primary and secondary Pelvic adhesions

Pelvic congestion Mittelschmerz Vulvodynia Uterine prolapse Ovarian cyst

Ovarian remnant syndrome Adenomyosis

Fibroids Ovarian cancer Cervical cancer

Torsion of adnexa Tubo-ovarian abscess Uterine fibroids Ectopic pregnancy

Abortion, threatened or incomplete

Gastrointestinal

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) Diverticulitis

Constipation Bowel obstruction Appendicitis Colon cancer Gastroenteritis

Genitourinary

• Interstitial cystitis

Urinary tract infection Urinary retention Renal calculi Pyelonephritis Ureteral lithiasis Bladder neoplasm

Musculoskeletal

• Scoliosis

Radiculopathy Arthritis Herniated disk Hernia

• Abdominal wall hematoma

Other

• Aortic aneurysm

Pelvic thrombophlebitis

• Acute porphyria

• Abdominal angina

Psychiatric, depression Somatization disorder

Prior or current physical or sexual abuse

Diagnoses of Gynecologic Origin Nongynecologic Diagnoses

Endometriosis

Chronic pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) Dysmenorrhea, primary and secondary Pelvic adhesions

Pelvic congestion Mittelschmerz Vulvodynia Uterine prolapse Ovarian cyst

Ovarian remnant syndrome Adenomyosis

Fibroids Ovarian cancer Cervical cancer

Torsion of adnexa Tubo-ovarian abscess Uterine fibroids Ectopic pregnancy

Abortion, threatened or incomplete

Gastrointestinal

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) Diverticulitis

Constipation Bowel obstruction Appendicitis Colon cancer Gastroenteritis

Genitourinary

• Interstitial cystitis

Urinary tract infection Urinary retention Renal calculi Pyelonephritis Ureteral lithiasis Bladder neoplasm

Musculoskeletal

• Scoliosis

Radiculopathy Arthritis Herniated disk Hernia

• Abdominal wall hematoma

Other

• Aortic aneurysm

Pelvic thrombophlebitis

• Acute porphyria

• Abdominal angina

Psychiatric, depression Somatization disorder

Prior or current physical or sexual abuse

Diagnoses of Gynecologic Origin Nongynecologic Diagnoses

Endometriosis

Chronic pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) Dysmenorrhea, primary and secondary Pelvic adhesions

Pelvic congestion Mittelschmerz Vulvodynia Uterine prolapse Ovarian cyst

Ovarian remnant syndrome Adenomyosis

Fibroids Ovarian cancer Cervical cancer

Torsion of adnexa Tubo-ovarian abscess Uterine fibroids Ectopic pregnancy

Abortion, threatened or incomplete

Gastrointestinal

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) Diverticulitis

Constipation Bowel obstruction Appendicitis Colon cancer Gastroenteritis

Genitourinary

• Interstitial cystitis

Urinary tract infection Urinary retention Renal calculi Pyelonephritis Ureteral lithiasis Bladder neoplasm

Musculoskeletal

• Scoliosis

Radiculopathy Arthritis Herniated disk Hernia

• Abdominal wall hematoma

Other

• Aortic aneurysm

Pelvic thrombophlebitis

• Acute porphyria

• Abdominal angina

Psychiatric, depression Somatization disorder

Prior or current physical or sexual abuse

The most common gynecologic-related causes of chronic pelvic pain identified by laparoscopy are endometriosis (see Chapter 26) and adhesions (Rapkin & Nathan, 2012). Other common causes include ovarian remnant, retained ovary syndrome, pelvic congestion syndrome, pelvic relaxation causing prolapse of gynecologic organs (e.g., uterine prolapse; see Chapter 25), subacute salpingo- oophoritis (see Chapter 20), cancer of gynecologic origin (see Chapter 27), and ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS).

Pelvic adhesions are coarse bands of tissue that connect organs to other organs or to the abdominal wall in places where there should be no connection. Adhesions can be caused by previous surgeries, infection, or endometriosis (Hoffman, 2012; Rapkin & Nathan, 2012; Styer, 2013). They may be the etiology for infertility, dyspareunia, and bowel obstruction (Styer, 2013). Currently, the causal role of adhesions in pelvic pain is unknown. The myriad of symptoms range from mild intermittent abdominopelvic pain to constant pain with gastrointestinal (constipation, bloating, dyschezia), gynecologic (dyspareunia, dysmenorrhea, focal lateral or

central pelvic and adnexal pain), and musculoskeletal symptoms (abdominal wall tenderness) (Styer, 2013). If symptoms are exacerbated during specific portions of the menstrual cycle (e.g., menses, luteal phase, follicular phase), then medical therapy should be considered with use of hormonal suppression of the cycle (Styer, 2013). If symptoms are constant, then use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and other forms of analgesics should be considered, with possible referral to

a pain specialist (Styer, 2013).

Etiology, diagnosis, and treatment of common breast disorders

Clinical signs and symptoms of ectopic pregnancy

Ectopic pregnancy is a potentially life-threatening form of pregnancy complication resulting from implantation of the fertilized egg outside the uterus, usually in the fallopian tube. With a prevalence of approximately 2% of reported pregnancies (Marion & Meeks,

2012), ectopic pregnancy is a leading differential diagnosis when a woman has lower abdominal pain in the first trimester. Risk factors include a history of pelvic inflammatory disease or infertility. However, if a woman who is newly pregnant is experiencing lower quadrant pain, it is important to rule out ectopic pregnancy even if she does not have risk factors. Any women with cervical motion tenderness on bimanual examination should be evaluated

for ectopic pregnancy, as should any woman early in pregnancy with pelvic or abdominal pain. Bleeding, ranging from spotting to the amount that occurs during a menstrual period, can also be a symptom (Crochet et al., 2013). If the woman’s hCG level is more than 3,000 mIU/mL, a gestational sac should be visible within the uterus. Ectopic pregnancies tend to have slowly rising hCG levels that increase but do not double within 48 hours.

Ectopic pregnancy is the implantation of a fertilized ovum in locations other than the uterine cavity. It is the second leading cause of maternal mortality in the United States (Marion & Meeks, 2012). Approximately 95% of all ectopic pregnancies occur in the fallopian tube (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists,

2008, reaffirmed 2014). Growth of the fetus in the fallopian tube puts the woman who is pregnant at high risk for pregnancy loss, tubal rupture, excessive blood loss, and future infertility due to tubal scarring. Box 31-1 summarizes risk factors associated with ectopic pregnancy.

Pelvic and abdominal pain and unexplained vaginal bleeding are the primary symptoms experienced by most women with ectopic pregnancy. The pain may be described as vague, sharp, diffuse, or unilateral. The woman may have had a time of amenorrhea, and pregnancy may or may not already be diagnosed. A ruptured ectopic pregnancy is characterized by a sudden onset of vaginal bleeding and sharp, severe, unilateral abdominal pain. Following rupture, symptoms of significant blood loss and resulting shock may include hypotension, shoulder pain, and breast tenderness.