Common Infections

1. Impetigo

Impetigo is a superficial bacterial infection of the skin. It is classified into primary

impetigo when there is a direct bacterial invasion of previously normal skin or secondary

impetig

...

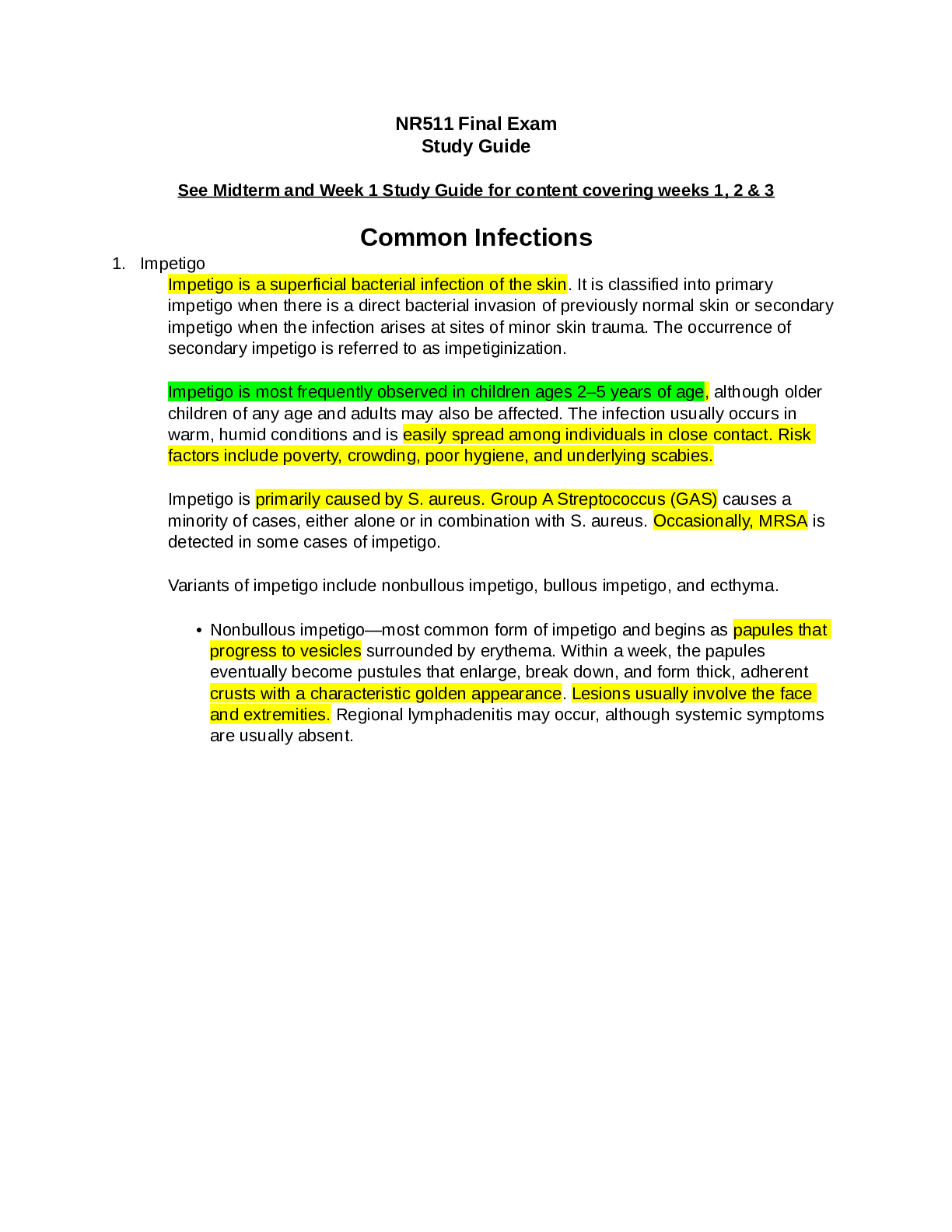

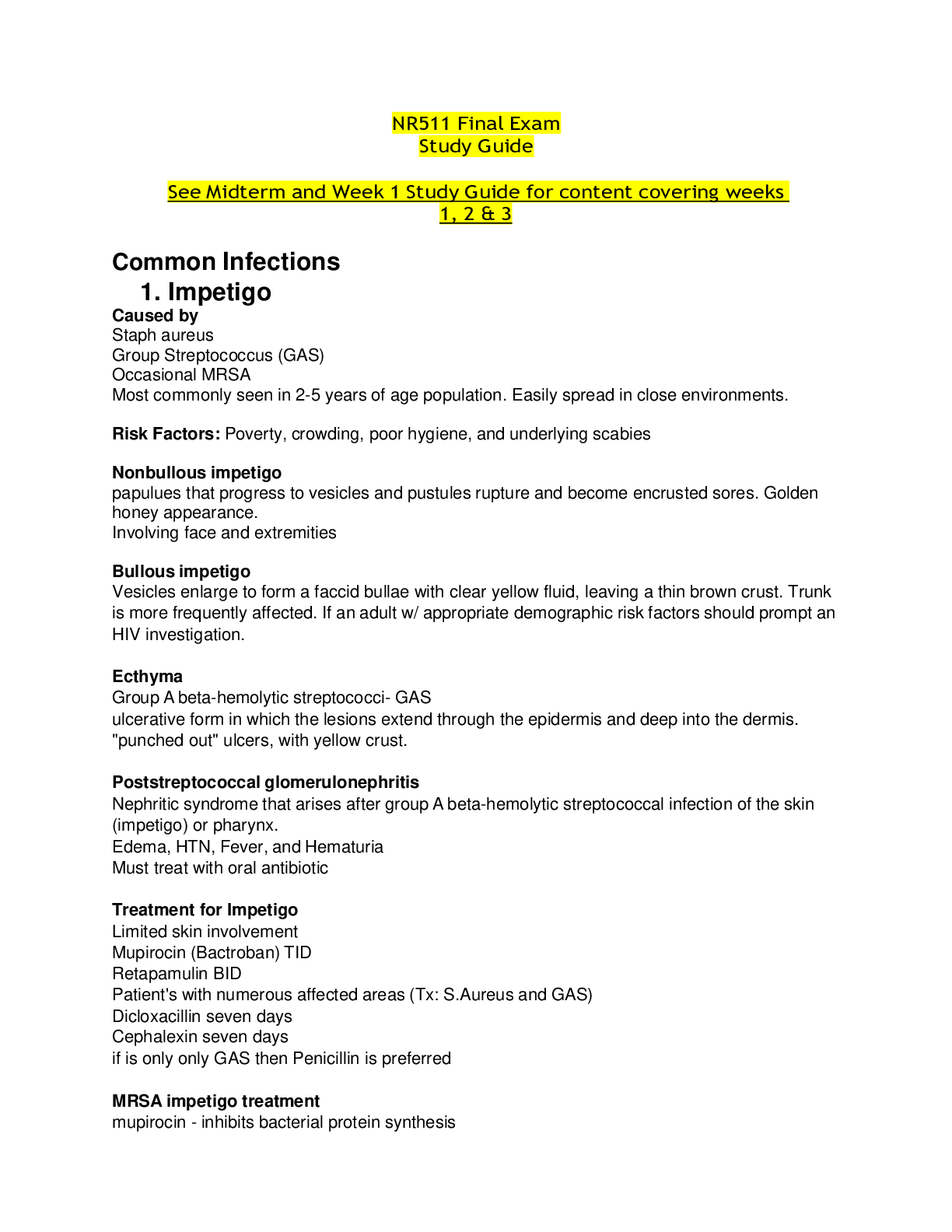

Common Infections

1. Impetigo

Impetigo is a superficial bacterial infection of the skin. It is classified into primary

impetigo when there is a direct bacterial invasion of previously normal skin or secondary

impetigo when the infection arises at sites of minor skin trauma. The occurrence of

secondary impetigo is referred to as impetiginization.

Impetigo is most frequently observed in children ages 2–5 years of age, although older

children of any age and adults may also be affected. The infection usually occurs in

warm, humid conditions and is easily spread among individuals in close contact. Risk

factors include poverty, crowding, poor hygiene, and underlying scabies.

Impetigo is primarily caused by S. aureus. Group A Streptococcus (GAS) causes a

minority of cases, either alone or in combination with S. aureus. Occasionally, MRSA is

detected in some cases of impetigo.

Variants of impetigo include nonbullous impetigo, bullous impetigo, and ecthyma.

• Nonbullous impetigo—most common form of impetigo and begins as papules that

progress to vesicles surrounded by erythema. Within a week, the papules

eventually become pustules that enlarge, break down, and form thick, adherent

crusts with a characteristic golden appearance. Lesions usually involve the face

and extremities. Regional lymphadenitis may occur, although systemic symptoms

are usually absent.

• Bullous impetigo—Bullous impetigo is seen primarily in young children in which the

vesicles enlarge to form flaccid bullae with clear yellow fluid, which later becomes

darker and ruptures, leaving a thin brown crust. The trunk is more frequently

affected. Bullous impetigo in an adult with appropriate demographic risk factors

should prompt an investigation for previously undiagnosed human

immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.

• Ecthyma—This form of impetigo, caused by group A, beta-hemolytic Streptococcus

(Streptococcus pyogenes), consists of an ulcerative form in which the lesions

extend through the epidermis and deep into the dermis. Ecthyma resembles

"punched-out" ulcers covered with yellow crust surrounded by raised violaceous

margins.

Poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis is a serious complication of impetigo (ecthyma).

This condition develops within 1–2 weeks following infection. Poststreptococcal

glomerulonephritis manifests with edema, hypertension, fever, and hematuria.

The diagnosis of impetigo often can be made on the basis of clinical manifestations.

A Gram stain and culture of pus or exudate is recommended to identify whether S.

aureus and/or a beta-hemolytic Streptococcus is the cause. However, treatment may be

initiated without these studies in patients with typical clinical presentations.

Bullous and nonbullous impetigo can be treated with either topical or oral therapy.

Topical therapy is used for patients with limited skin involvement whereas oral therapy is

recommended for patients with numerous lesions. Unlike impetigo, ecthyma should

always be treated with oral therapy.

Benefits of topical therapy include fewer side effects and lower risk for contributing to

bacterial resistance compared with oral therapy. Topical choices to treat impetigo include

the following medications for 5 days.

• Mupirocin three times daily

• Retapamulin twice daily

Extensive impetigo and ecthyma should be treated with an antibiotic effective for both S.

aureus and streptococcal infections unless cultures reveal only streptococci. Dicloxacillin

and cephalexin are appropriate treatments. A 7-day course of oral antibiotic treatment is

recommended. If only streptococci are detected in extensive impetigo or ecthyma, oral

penicillin is the preferred therapy.

MRSA impetigo can be treated with doxycycline, clindamycin, or trimethoprimsulfamethoxazole (Bactrim). Crusted lesions can be washed gently. Children can return

to school 24 hours after beginning an effective antimicrobial therapy. Draining lesions

should be kept covered.

Quiz: Sally, aged 25, presents with impetigo that has been diagnosed as infected

with staphylococcus. The clinical presentation is pruritic tender, red vesicles

surrounded by erythema with a rash that is ulcerating. She has not been adequately

treated recently. Which type of impetigo is this?

a. Bullous impetigo

b. Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (SSSS)

c. Nonbullous impetigo

d. Ecthyma

2. Staphylococcal Scalded Skin Syndrome

Caused by Staphylococcus aureus, it’s a variant of bullous impetigo:Epidermal necrosis

caused by bacterial exotoxins, resulting in the epithelial layer peeling off in large,

sheetlike pieces; mimics scalded-skin thermal burn. This serious infection is more

commonly seen in children and usually begins in the intertriginous areas.

3. Cellulitis

Cellulitis is an acute infection as a result of bacterial entry via breaches in the skin

barrier. As the bacteria enter the subcutaneous tissues, their toxins are released which

causes an inflammatory response.

Cellulitis and erysipelas is almost always a unilateral infection with the most

common site of infection being the lower extremities.

Cellulitis involves the deeper dermis and subcutaneous fat.

Cellulitis is observed most frequently among middle-aged individuals and older

adults.

The vast majority of pathogens associated with cellulitis are from either

Streptococcus or Staphlococcus bacteria. The most common are beta-hemolytic

streptococci (groups A, B, C, G, and F), and S. aureus (gram +)

Both erysipelas and cellulitis manifest with areas of skin erythema, edema,

warmth and pain. Fever may be present. Additional manifestations of cellulitis

and erysipelas include lymphangitis and inflammation of regional lymph nodes.

Edema surrounding the hair follicles may lead to dimpling in the skin, creating an

appearance reminiscent of an orange peel texture called "peau d'orange".

Cellulitis may present with or without purulence

patients with cellulitis tend to have a more indolent course with development of

localized symptoms over a few days.

Many patients with cellulitis have underlying such as tinea pedis, lymphedema,

and chronic venous insufficiency. In such patients, treatment should be directed

at both the infection and the predisposing condition if modifiable.

Patients with cellulitis or erysipelas in the absence of abscess or purulent

drainage should be managed with empiric antibiotic therapy. Patients with

drainable abscess should undergo incision and drainage.

I. Describe an appropriate empiric antibiotic treatment plan for cellulitis

should be managed with empiric therapy for infection due to beta-hemolytic

streptococci and methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus (MSSA) with:

• Cephalexin 500 mg four times daily (alternative for mild penicillin allergy)

• Clindamycin 300 mg to 450 mg four times daily (alternative for severe penicillin

allergy)

Good choices for uncomplicated cases of cellulitis that are not associated with

human or animal bites include dicloxacillin or cephalexin for 10 to 14 days.

If pt has severe PCN allergy rx erythromycin

If caused by animal or human bite: amoxicillin-clavulanic acid (augmentin) for 2

weeks

The coverage for MRSA is achieved by adding to amoxicillin one of the following:

Bactrim DS twice daily

Doxycycline 100 mg twice daily

Minocycline 200 mg orally once, then 100 mg orally every 12 hours

If clindamycin is used, no additional MRSA coverage is needed.

Risk factors for community-associated methicillin-resistant S. aureus (CA-MRSA) include the

following.

• Antibiotic use secondary to antibiotic selective pressure. Use of cephalosporins and

fluoroquinolones strongly correlates with the risk for MRSA colonization and infection.

• HIV infection

• Hemodialysis

• Long-term care facilities

Patients with drainable abscess should undergo incision and drainage. For patients undergoing

incision and drainage of a skin abscess, some experts suggest antibiotic treatment under some

conditions.

• Single abscess ≥2 cm

• Multiple lesions

• Extensive surrounding cellulitis

• Associated immunosuppression or other comorbidities

• Systemic signs of toxicity (fever >100.5° F/38° C)

• Presence of an indwelling medical device (such as prosthetic joint, vascular graft, or

pacemaker)

• High risk for transmission of aureus to others (such as in athletes or military personnel)

Quiz: Ian, age 62, presents with a wide, diffuse area of erythematous skin on his left lower leg

that is warm and tender to palpation. There is some edema involved. You suspect:

a. Necrotizing fasciitis. c. Cellulitis.

b. Kaposi's sarcoma. d. A diabetic ulcer.

4. Erysipelas

Cellulitis and erysipelas are two of the most common skin and soft tissue infections.

Erysipelas involves the upper dermis, and there is clear demarcation between

involved and uninvolved tissue.

An older name for erysipelas is “St. Anthony’s fire.” Despite the superficial nature

of this infection, erysipelas should not be taken lightly, because it can be fatal if it

is not treated promptly (especially in the very young and the elderly).

Erysipelas is sometimes seen after an episode of strep throat.

The most common sites of involvement are the face (especially the cheeks) and

the lower legs.

Erysipelas occurs in young children and older adults.

Erysipelas results almost always results from a group A strep infection.

erysipelas is non-purulent.

Patients with erysipelas tend to have acute onset of symptoms with systemic

manifestations including fever and chills

Classic descriptions of erysipelas note "butterfly" involvement of the face.

Involvement of the ear (Milian's ear sign) is a distinguishing feature for

erysipelas, since this region does not contain deeper dermis tissue.

Quiz: Which of the following types of cellulitis is a streptococcal infection of the

superficial layers of the skin which does not involve the subcutaneous layers?

a. Necrotizing fasciitis c. Erysipelas

b. Periorbital cellulitis d. "Flesh-eating" cellulitis

5. Necrotizing fasciitis

Considered as a severe case of cellulitis must refer to ER, can be a differential diagnosis

of cellulitis

Defined as deep infection that results in progressive destruction of the muscle fascia.

The affected area may be erythematous, swollen, warm, and exquisitely tender. Pain out

of proportion to exam findings may be observed.

The hallmark of this infection is its rapid progression and the severity of the

symptoms. The progress of the infection is measured in terms of hours instead of

days, and the border can be seen to literally spread in just a few hours.

This infection is caused by “flesh-eating bacteria,” and loss of life or limb is a

potential complication.

Quiz: Mark has necrotizing fasciitis of his left lower extremity. Pressure on the skin reveals

crepitus due to gas production by which anaerobic bacteria?

a. Staphylococcal aureus c. S. pyrogenes

b. Clostridium perfringens d. Streptococcus

6. Mammalian bites

Soft tissue trauma caused by animal and human bites have serious clinical implications

because of the potential for complications.

Bite wounds should be irrigated copiously with sterile saline, and grossly visible debris

should be removed. Prophylactic antibiotics are administered to patients who present for

evaluation of a bite wound who do not yet have signs or symptoms of infection in the

following circumstances.

• Deep puncture wounds (especially due to cat bites)

• Wounds requiring surgical repair

• Moderate to severe wounds with associated crush injury

• Wounds in areas of underlying venous and/or lymphatic compromise

• Wounds on the hand(s) or in close proximity to a bone or joint

• Wounds on the face or in the genital area

• Wounds in immunocompromised hosts

Amoxicillin/clavulanate 875 mg/125 mg twice daily is the agent of choice. Alternative

antibiotics include one of the following agents with activity against Pasteurella.

• Doxycycline 100 mg twice daily

• Bactrim DS twice daily

• Penicillin VK 500 mg four times daily

• Ciprofloxacin 500 mg twice daily

Plus one of the following agents with anaerobic activity.

• Metronidazole 500 mg three times daily

• Clindamycin 450 mg three times daily

First-generation cephalosporins and macrolides should be avoided. The duration of

prophylactic oral antibiotics is 3–5 days, with close follow-up. Tetanus toxoid should be

given to those who have completed a primary immunization series but who received the

most recent booster 5 or more years ago.

[Show More]