Chapter 8

An Introduction to Pharmacogenomics

Optimal drug treatment requires selection of the best possible agents with close

monitoring of pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, adverse drug reactions, and the cost

...

Chapter 8

An Introduction to Pharmacogenomics

Optimal drug treatment requires selection of the best possible agents with close

monitoring of pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics, adverse drug reactions, and the cost

of different agents.

Pharmacogenomics is the branch of science concerned with the identification of the

genetic attributes of an individual that lead to variable responses to drugs. Interestingly,

the science has evolved to also consider patterns of inherited alterations in defined

populations, such as specific ethnicities, that account for variability in

pharmacotherapeutic responses.

Until recently, the ultimate goal of pharmacogenomics had been the development of

prediction models to forecast debilitating adverse events in specific individuals and, more

recently, across populations based on similarities in age, gender, or more commonly, race

or ethnicity, as contrasted with the rest of the population. However, in spite of this newer

usage, pharmacogenomics may predict the extreme deviation of some patients from

predictable pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic responses: the idiosyncratic response.

Pharmacogenomics seeks to identify patterns of genetic variation that are subsequently

employed to guide the design of optimal medication regimens for individual patients.

With empiric therapy, interindividual (allot pic) variation in drug response occurs—with

patient outcomes varying from a complete absence of therapeutic response to potentially

life-threatening adverse drug reactions (ADRs).

Genetic differences may account in part for some of the well-documented variability in

response to drug therapy. Obviously, many factors other than genetics—such as age, sex,

other drugs administered, and underlying disease states—also contribute to variation in

drug response. However, inherited differences in the metabolism and disposition of drugs

and genetic polymorphisms in the targets of drug therapy (e.g., metabolizing enzymes or

protein receptors) can have an even greater influence on the efficacy and toxicity of

medications. Interestingly, age, gender, and endemic geographical differences may

themselves emerge as phenotypic consequences of differential epigenetic control. This

implies that heterogeneity in the control of gene expression based upon age, gender, and

geographic location is itself a life-long changing process that is under the control of

molecular “epigenetic” switches that either activate or inhibit groups of genes as a unit.

Genetics Revisited

An individual’s genetic makeup (or genotype) is derived as a result of genetic

recombination or “mixing” of genes from that individual’s parents. All the DNA

contained in any individual cell is known as the genome of the individual, a word formed

by the combination of “gene” and “chromosome,” and thus represents all the genes that

individual can express.

The Human Genome Project has sought not only to identify and correlate SNPs with

phenotypic differences but also to record and map haplotypes as well.o The completion of the Human Genome Project, as well as the mapping of SNPs

and haplotypes, has allowed the field of pharmacogenomics to understand the

variability of drug metabolism seen across individuals and populations.

Standard adopted nomenclature is used in pharmacogenomics and pharmacogenetics. Of

the various mutant variants of a specific gene, each variant is numerically and

sequentially named starting with the “wild-type” or normal or nonmutated copy of the

gene.

o Thus, for instance, CYP2D6 written in italics refers to the normal copy of the

gene, whereas CYP2D6*1 (pronounced “star 1”) refers to the first identified

natural variant (mutant) copy of this gene.

History of Pharmacogenetics

Since 1962, the term has been used to refer to the effects of genetic differences on a

person’s response to drugs.

The rate of acetylation of a drug such as isoniazid is clinically relevant because it

determines the rate of elimination of the drug from the body. Thus, individuals known as

slow acetylates will metabolize the drug slowly, allowing greater residence time in the

body and enhanced toxicity. It is a pharmacogenomic variation, which is responsible for

slow or fast acetylates as explained below.

Pharmacogenomics

The ultimate promise of pharmacogenomics is the possibility that knowledge of the

patient’s DNA sequence might be used to enhance drug therapy to maximize efficacy, to

target drugs only to those patients who are likely to respond, and to avoid ADRs.

The long-term expected benefits of pharmacogenomics are selective and potent drugs,

more accurate methods of determining appropriate drug dosages, advanced screening for

disease, and a decrease in the overall cost to the health-care system in the United States

caused by ineffective drug therapy.

Genetic Differences in Drug Metabolism

First realized by the observation that sometimes very low or very high concentrations of

drug were found in some patients despite their having been given the same amount of

drug.

Genetic Polymorphism

o Occurs when a difference in the allele(s) responsible for the variation is a

common occurrence.

o Under such circumstances, mutant genes will exist somewhat frequently alongside

wild-type genes. The mutant genes will encode for the production of mutant

proteins in these populations. The mutant proteins will, in turn, interact with drugs

in different manners, sometimes slight, sometimes significant. Monogenic traits

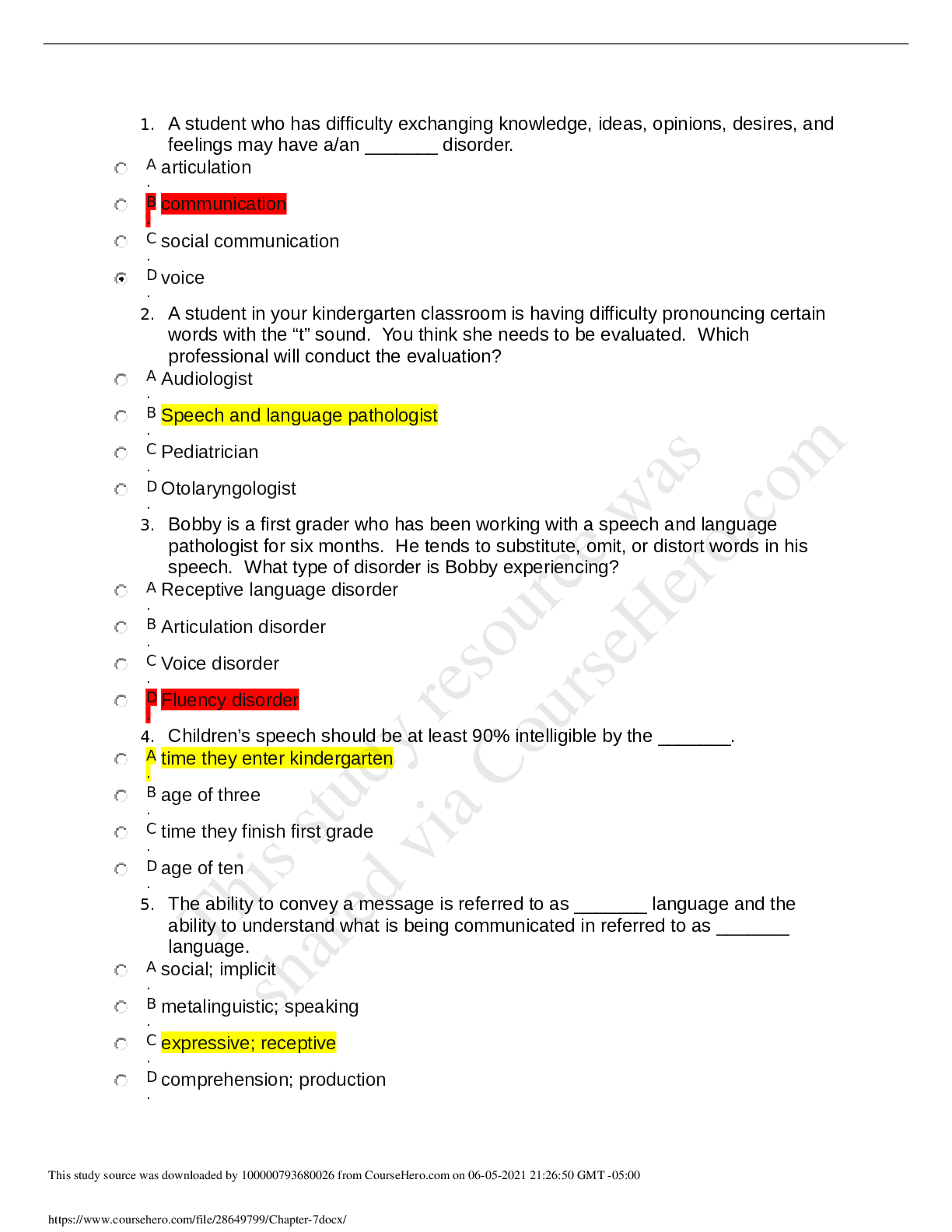

by themselves cannot explain the complexity of drug metabolism.o Four different phenotypes categorize the effects that genetic polymorphisms have

on individuals: poor metabolizers (PMs) lack a working enzyme; intermediate

metabolizers (IMs) are heterogeneous for one working, wild-type allele and one

mutant allele (or two reduced-function alleles); extensive metabolizers (EMs)

have two normally functioning alleles; and ultrarapid metabolizers (UMs) have

more than one functioning copy of a certain enzyme.

Phase I and Phase II Metabolism

o Drug metabolism generally involves the conversion of lipophilic substances and

metabolites into more easily excretable water-soluble forms. Drug metabolism

takes place mostly in the liver and is divided into two major categories, phase I

(oxidation, reduction, and hydrolysis reactions) and phase II metabolism

(conjugation reactions).

Metabolizer Phenotype Effect on Drug Metabolism Clinical Implications

Poor to intermediate

metabolizers

Slow Prodrug will be metabolized

slowly into active drug

metabolite. May have

accumulation of prodrug.

Active drug will be

metabolized slowly into

inactive metabolite. Potential

for accumulation of active

drug. Patient requires lower

dosage of medication.

Ultra rapid metabolizers Fast Prodrug rapidly metabolized

into active drug. No dosage

adjustment needed.

Active drug rapidly

metabolized into inactive

metabolites leading to

potential therapeutic failure.

Patient requires higher dosage

of active drug.

o Phase I metabolism enzymes are responsible for approximately 59% of the

adverse drug reactions.

o CYPs are generally located in the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and the

mitochondria in human cells, of which the ER isoforms are of particular

importance to the field of drug metabolism. In terms of their organ distribution,

they are found in greater amounts in the liver and the intestine and to a somewhat

lesser extent in other organs, such as the skin, brain, lungs, and kidneys.o Hepatic, renal, and intestinal ER CYPs are involved in the biotransformation of a

plethora of drugs and endogenous substrates in humans mainly by oxygenation of

the target substrate molecule and mediated by differential oxidation states of the

central iron atom in the enzyme. Due to this oxygenation reaction, CYPs are

classified as monooxygenases.

Specific CYP450 Enzymes

o CYP2D6

Up to 25% of drugs are metabolized by this.

Exhibits polymorphism.

Acts on many xenobiotics, such as SSRI fluoxetine, TCAs, beta blockers,

CCB (diltiazem), theophylline, and tamoxifen.

Table 8-3

Research has shown that while approximately 10% of Caucasians, up to

7% of African Americans, and 4.8% of Asians have the “poor

metabolizer” (PM) phenotype, 5% of Caucasians and 4.9% of African

Americans have the “ultra rapid metabolizer” (UM) phenotype.

Table 8-2

o CYP2D6 and Tamoxifen

The role is not so much the metabolism of this drug as it is to activate it by

conversion to endoxifen inside the cell.

o CYP2D6 and Opioid Analgesics (Codeine)

Codeine relies on CYP2D6 enzymes to convert them to their active form,

morphine.

UM types may not experience the analgesic effects of the drug at normal

therapeutic doses, and PMs may not be able to convert codeine to its

active metabolite morphine, thus experiencing little or no clinical benefit.

o Genetic Testing for CYP2D6 Polymorphisms

CYP2C9

The primary route of metabolism for about a hundred different

drugs in humans.

While some CYP2C9 substrates are the more common drugs, such

as phenytoin, glipizide, and losartan, other drug substrates include

those that evince a narrow therapeutic index, such as the coumarinrelated anticoagulant agents warfarin and acenocoumarol.

CYP2D9 and Warfarin

o Warfarin is one of the most effective, cheapest, and widely

prescribed anticoagulant drugs that act by inhibiting the

enzyme vitamin K epoxide reductase, which prevents the

formation of functional vitamin K.

o This action in turn inhibits the activation of clotting factors

in the liver, causing the anticoagulant effect.

o Clinically, warfarin maintenance dosing requirements are

lower in patients with CYP2C9*2 polymorphisms andfurther reduced in patients with CYP2C9*3 variants

(Gulseth, Grice, & Dager, 2009), making these two the

most common “reduced function variants” for the CYP

gene in terms of its effect on warfarin.

o In addition, patients with homozygous presentation of a

CYP2C9 mutation appear to have a greater reduction in

dosing requirement than do heterozygotes. Approximately

one-third of the population carries at least one allele for the

slow-metabolizing form of CYP2C9

Interestingly, the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

celecoxib and flubiprofen have received “use with caution” in PM

label warnings from the FDA owing to CYP2C9 polymorphism.

CYP3A4

Responsible for up to 50% of drug metabolism.

Examples of these classes include azole antifungals, CCBs,

antihistamines, anticonvulsants, antimicrobials, and

corticosteroids.

Predicting the onset and offset of these effects is very difficult.

The time to onset and offset of drug-drug interactions is closely

related to each drug’s half-life and the half-life of enzyme

production.

Clinically significant drug interactions in this setting may increase

the risk of toxicity.

Table 8-5

Close monitoring is required when prescribing drugs that induce or

inhibit CYP3A4 enzymes.

P-Glycoprotein

A membrane-bound, ATP-dependent transport system responsible for the efflux of a

variety of xenobiotics from cells to the extracellular fluid.

This includes the ejection of drugs from cells, usually against their concentration

gradients. Pgp, also known as multidrug resistance (MDR1) protein, is the product of the

ABCB1 and ABCB4 genes and is a member of adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-binding

family of proteins.

Differential expression of Pgp may explain tissue-specific and temporal variations in

efflux efficiency in different cells.

The more Pgp protein expressed by the cell, the greater the efflux potential of xenobiotics

such as anticancer drugs.

Over 50 SNPs within the ABCB1 gene have been identified, which may lead to variability

in drug responses.

Pharmaceutically relevant examples of this include the variation in drug response to

agents such as antiepileptic drugs, select cardiovascular agents, and so on. Interestingly, P-glycoprotein at the site of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract effluxes

hydrophilic drugs out of the cell and inhibits drug absorption through the GI tract (Howe,

2009). As drugs passively diffuse through the GI tract, Pgp pumps move drugs from

cytoplasmic areas to extracellular fluid. Some examples of substrates of P-glycoprotein

include carvedilol, diltiazem, and digoxin (Howe, 2009).

Several antiepileptic drugs such as phenytoin, carbamezapine, lamotrizine, phenobarbital,

valproic acid, and gabapentin are substrates or inhibitors of Pgp, but there is considerable

controversy in the literature regarding these.

In the case of digoxin, Pgp affects the level of digoxin available for absorption and

elimination (Howe, 2009). P-glycoprotein inhibitors include verapamil, quinidine,

cyclosporine, and ketoconazole (Howe, 2009). If an inhibitor of P-glycoprotein is

administered, then blood levels of substrates will rise, as seen if quinidine is administered

with digoxin.

Drugs can be categorized as reversible or suicidal inhibitors or P-glycoproteins.

Clinical Implications of Pharmacogenomics

Adverse Drug Reactions

o 56% of drugs cited in ADR studies are metabolized by polymorphic phase I

enzymes, of which 86% are P450s.

Warfarin

o Although genetic testing prior to prescribing has not yet been required by the

FDA, numerous warfarin dosing calculators exist on the Web where a clinician

can insert clinical information about the patient, including genetic test results and

indications, and a dosing regimen will be calculated or “individualized” for that

patient.

Pharmacogenetic Testing Prior to Prescribing

o Within the anticoagulant drug class, warfarin is a drug with a narrow therapeutic

index.

o Patients with CYP2C9 variations require more time to achieve the International

Normalized Ratio, or INR, and are at an increased risk for bleeding; they may also

require lower doses of warfarin to achieve and maintain therapeutic INR.

o Thus, if there are indications of inherited differences in these genes, the patient

should be genotyped.

o However, monitoring INR is still as much of a requirement while dosing warfarin

as before.

o Generally, cell samples are collected from the mouth or from blood.

o The pharmacogenetic tests mentioned on drug labels can be classified as “test

required,” “test recommended,” and “information only.” Currently, four drugs are

required to have pharmacogenetic testing performed before they are prescribed:

cetuximab, trastuzumab, maraviroc, and dasatinib.

o In December 2007, the FDA added a Black-Box Warning on the carbamazepine

label, recommending testing for the HLA-B*1502 allele in patients with Asian

ancestry before initiating carbamazepine therapy because these patients are athigh risk of developing carbamazepine-induced Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS)

or toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN).

o Table 8-7

[Show More]